Foreign-backed figures embedded in post-colonial systems do not produce sovereignty

Nelson Chamisa’s political trajectory sits squarely within the same post-independence governance system that has defined Zimbabwe since 1980. His rise has not challenged this system’s core architecture but instead helped to reproduce it. Chamisa gained control of the opposition party following Morgan Tsvangirai’s death, bypassing internal elections and procedural mandates in the process. There was no party congress, transparent leadership transition nor participatory constitutional process. This style of takeover mirrored the same authoritarian habits long associated with ZANU-PF leadership.

His approach to political organisation has lacked internal accountability, long-term strategic clarity, or policy-driven mobilisation. He has failed to build clear institutional frameworks within his movements. Leadership remains centred on his personality rather than on institutional frameworks. Succession planning is undefined, mid-level leadership remains undeveloped, and there is an absence of structured ideological education for party members. The political culture surrounding him reflects celebrity status rather than political substance. Leadership built on fame and visibility without clear ideological grounding becomes vulnerable to foreign manipulation and public confusion.

( 1 August 2008, Zanu PF killed 6 protesters)

During protests on 1 August 2018, six Zimbabweans were shot by the military in broad daylight. International cameras broadcast the killings as they happened. When questioned, Chamisa referred to the protesters as “stupid,” a remark he has never publicly withdrawn or corrected. That comment revealed a clear disconnect between his leadership image and his alignment with the people. No leader who respects the political cost of human life uses language that distances them from such tragedies. A person leading a democratic movement does not describe unarmed civilians killed by the army as fools.

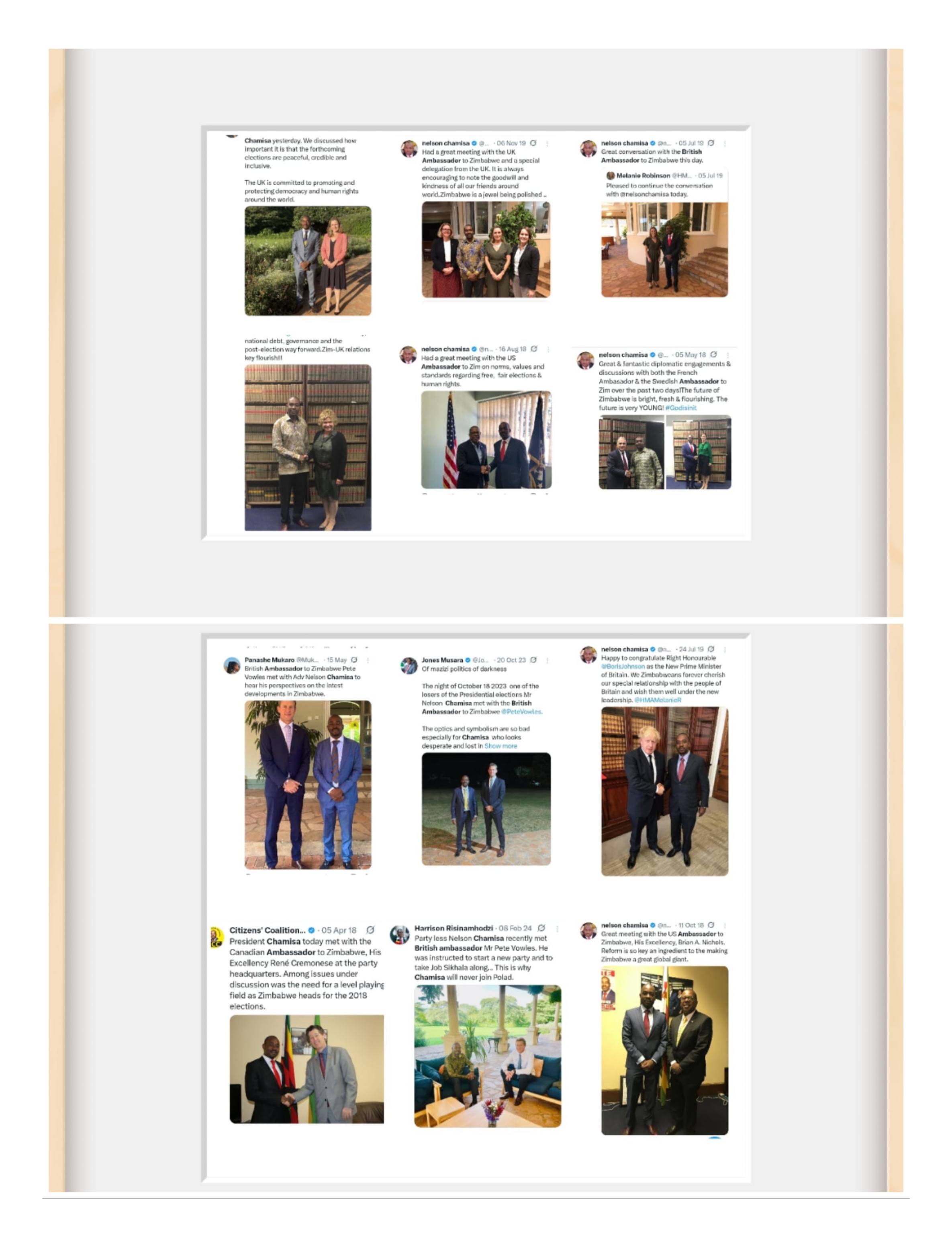

Chamisa’s financial and diplomatic relationships are closely tied to foreign governments, non-governmental organisations, and Western donor networks. These affiliations are maintained through consistent diplomatic engagement and material support from institutions with longstanding political and economic interests in Zimbabwe. These institutions represent external political interests that benefit from Zimbabwe’s continued dependency on foreign capital, policy advice, and trade structures. Chamisa maintains relations with ambassadors from Western states, appears in Western-aligned summits, and receives consistent positive media treatment from international outlets. Leaders who directly confront neocolonial systems do not receive such treatment. No black African leader who has his people at heart, willing to die serving the wishes of his people ever gets photo-ops with Rome’s highest servants, never !

There has been no policy framework from Chamisa that targets the core pillars of Zimbabwe’s dependency. He has not publicly rejected structural adjustment programmes or IMF loan conditions, nor does he challenge the dominance of foreign corporations over mining rights or banking infrastructure. He has avoided engagement with colonial-era land frameworks that remain largely intact under post-independence legislation. No meaningful economic sovereignty programme has emerged from his leadership. In place of a defined programme for economic sovereignty, there has been a continued reliance on externally driven development models. Chamisa has never presented a credible strategy for dismantling the colonial state’s economic legacies. There is no direct mention of Western-backed financial institutions, legal codes, or private capital structures that control Zimbabwe’s key resources. His appeals to reform lack precision, omitting any identification of the legal, financial, and institutional systems that sustain dependency. Without confronting these structural mechanisms, proposed changes remain superficial and reinforce the existing order. The result is a leadership style that avoids confrontation with capital power and instead promotes surface-level adjustments.

In contrast, African Economic Sovereigntists across the Sahel region are pursuing state-led reconstruction programmes that challenge colonial frameworks directly. Leaders in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger are using the state as a vehicle for economic recovery, political education, and social reorganisation. They have expelled foreign troops, withdrawn from colonial monetary unions, and rejected conditional financing. These governments are nationalising key sectors, reclaiming resource rights, and relaunching local production capacity. Their strategies focus on restoring control over money supply, energy infrastructure, food systems, technological development, and information access.

These states are building internal institutions to reverse the effects of colonial education models that normalised elite worship, foreign loyalty, and political passivity. They are training new leadership based on ideological commitment rather than public fame or religious symbolism. In these countries, political campaigns are rooted in sovereignty frameworks, not donor-funded campaign models.

Chamisa’s politics lack this structural engagement. His public communication strategy leans heavily on religious themes and spiritual rhetoric. He frames political leadership as a divine calling rather than a contractual responsibility. This undermines political accountability and removes political discourse from the realm of policy and institutional critique. A population trained to associate political legitimacy with faith-based language is less likely to demand programme details, legal reforms, or structural clarity.

Post-colonial political systems have conditioned African voters to choose leadership based on charisma, emotional symbolism, and media coverage. This conditioning is not accidental as it reflects decades of colonial-era education reforms that removed civic instruction and replaced it with passive obedience. In Zimbabwe, leadership is increasingly framed around image, not ideological substance. Chamisa benefits from this as his popularity reflects a cultivated media presence and public frustration with ZANU-PF, not a grounded alternative economic or political programme.

No visible evidence exists to suggest that Chamisa intends to confront the foundations of Western control in Zimbabwe. He has not taken clear positions against foreign debt institutions, corporate monopolies, or legacy white capital. His proposals for attracting foreign direct investment amount to further consolidation of external economic dominance. He speaks of reforms but never addresses land redistribution, banking sovereignty, or national ownership of key industries.

After both the 2018 and 2023 disputed elections, Chamisa failed to organise sustained legal challenges, mass mobilisation, or civic resistance. His responses were sporadic, inconsistent, and disorganised. Popular momentum from voters vanished without strategic direction. A leader committed to democratic change cannot afford to disappear when the public demand action. These failures embolden the ruling party and demobilise political participation.

Chamisa’s international positioning remains acceptable to global institutions that benefit from the current political setup. He is not sanctioned, excluded, or treated as a threat. No Western power regards him as a disruptive political actor. This pattern is consistent with figures of controlled opposition. He channels dissatisfaction through elections that do not result in power transfer, while shielding the system from more radical challenges.

The political culture of Zimbabwe has become a managed arena of power retention, donor influence, and elite accommodation. Elections operate as rituals to renew consent, rather than instruments of transformation. Political elites on all sides, including the opposition, are trained and funded by the same global architecture. Their programmes are shaped by international consultancy firms, donor platforms, and policy advisors whose interests do not align with African sovereignty.

Chamisa operates within the same structural and ideological framework that has sustained Zimbabwe’s political stagnation since independence. His leadership has not resulted in the creation of durable institutions capable of defending electoral outcomes or resisting sustained state repression. Policy proposals under his tenure have not addressed the foundations of economic dependency, nor have they presented a roadmap for disengaging from colonial-era legal and financial frameworks. His political vision remains confined to the boundaries of the post-independence settlement, offering no meaningful departure from the system that produced the present national crisis. Assertions that his leadership represents a break from past governance patterns are not substantiated by any measurable actions or outcomes.

ZANU PF’s failure lies not only in authoritarian governance but in its decision to preserve the legal and economic arrangements negotiated at Lancaster House. These agreements entrenched the privileges of white capital, foreign banks, and multinational corporations, effectively protecting settler wealth under the banner of political independence. Robert Mugabe’s administration maintained this framework throughout his rule, consolidating power through patronage networks that channelled state resources to a small black elite while shielding the interests of foreign capital. Emmerson Mnangagwa has continued the same pattern, repackaging the system as a new dispensation without altering its foundations. Similar dynamics unfolded in South Africa, where Nelson Mandela’s post-apartheid government signed agreements that safeguarded corporate ownership and inherited economic hierarchies. In both cases, a political settlement was exchanged for the continuation of an extractive system, managed by a compliant local elite. This structure has been sustained under the so-called stability doctrine, which prioritises foreign investor confidence over domestic transformation. The result has been economic stagnation for the majority, persistent inequality, and sustained external control of critical sectors. Chamisa has offered no position on dismantling this structure, nor has he addressed the broader architecture of post-colonial economic extraction that underpins it.

Real national liberation requires rejection of the entire post-independence framework that was structured through colonial legal codes, global finance rules, and elite political continuity. That change will not come from politicians celebrated by Western platforms or promoted through donor networks. It will emerge through grounded mobilisation, local organisation, and a break from foreign dependency.

Zimbabwe’s crisis is structural and no candidate operating within the existing party structures and donor-funded models can deliver national sovereignty. Until that system is dismantled, every new leader will follow the same script, with different branding and faces. Chamisa is no exception to that pattern.

Authored By:

If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, Popular Information could expose more lies, root out more corruption, and call out more hypocrites. So, if you can afford it, please support this work.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

(True knowledge is power, those borrowed education systems maintain the lies, hence zero progress)

Leave a comment