Unpacking Covert Operations and Foreign Meddling in Kathmandu

The events unfolding in Nepal represent a textbook example of externally engineered political unrest designed to destabilise a strategically positioned state. The official narrative pushed by Western media is that young citizens spontaneously erupted into protest over restrictions on social media. Local reporting presents a very different picture. The protests were not spontaneous uprisings of digitally aware youth but the product of careful cultivation by networks funded and directed by the United States through organisations such as the National Endowment for Democracy. Analysts have long documented the direct involvement of such groups in regime change efforts across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, and the pattern in Nepal matches every detail of those operations.

The immediate trigger was the government’s decision to restrict foreign social media platforms after American corporations refused to comply with Nepalese law on information security and data regulation. The ban represented an attempt by Kathmandu to assert control over its own digital space, a move fully consistent with the sovereign right of any state to regulate its communications environment. The United States and its information corporations perceived this as intolerable. Social media platforms operated from Silicon Valley have become the principal means through which Western states extend influence over younger populations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Once access to these platforms is blocked, Washington loses a powerful instrument of political manipulation. The unrest in Nepal therefore served as direct punishment for the government’s decision to challenge American companies and by extension American geopolitical power.

The protests escalated with extraordinary speed. Within days of the restrictions, crowds of young people between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five stormed government buildings in Kathmandu, set fire to the parliament complex, and forced the resignation of the Prime Minister. Reports confirm at least nineteen deaths during the clashes. Ministers were evacuated from their residences by army helicopters, demonstrating the scale of the threat to state institutions. None of this represents a natural evolution of protest. It reflects planning, financing, and organisational methods consistent with previous colour revolutions, from Serbia in 2000 to Ukraine in 2004 and 2014, and Hong Kong in 2019.

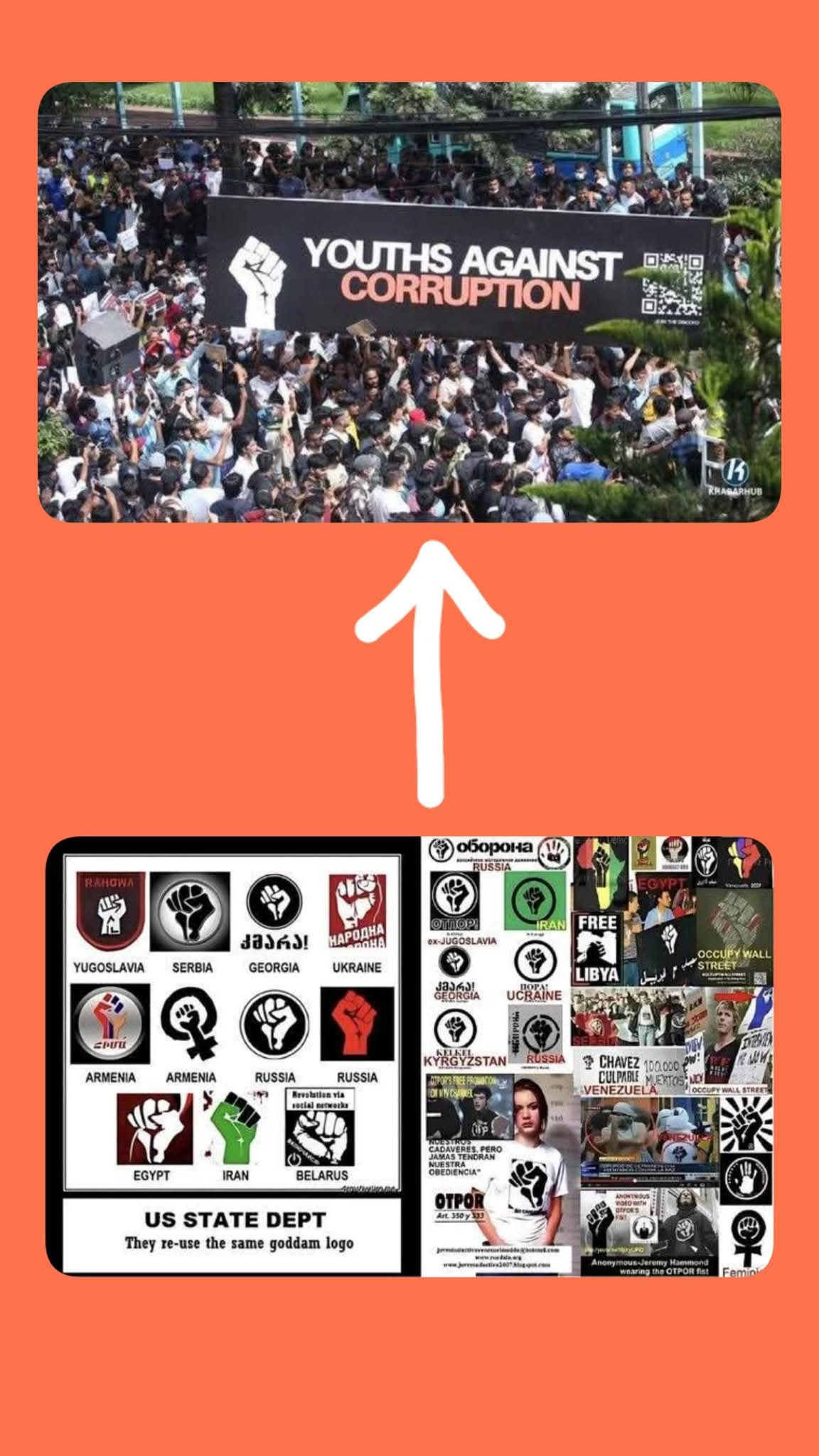

Even protest imagery was recycled from other theatres of unrest. Flags from Japanese animation series were waved by Nepalese demonstrators, precisely the same iconography promoted during American-backed violence in Indonesia weeks earlier. Such repetition is no accident. It demonstrates the degree to which cultural symbols are selected and deployed by organisers to create instant identification, emotional mobilisation, and media-friendly visuals. Analysts examining NED-linked operations in Indonesia found written evidence of coordination between US embassy officials and local political groups. Nepal now exhibits the same hallmarks, from coordinated social media campaigns to carefully staged confrontations with riot police designed for international media distribution.

The government’s initial ban on foreign social media was quietly lifted after the first wave of violence, a concession noted by the BBC. This outcome confirms the strategic intent behind the protests, to reverse Nepalese attempts at information sovereignty and ensure continued Western access to the digital space of a state located between India and China. Analysts note that such concessions never satisfy organisers. Rather, they embolden further demands until a compliant political leadership is installed. The resignation of the Prime Minister should therefore be understood not as a tactical retreat but as a forced removal under direct external pressure.

(George Soros network is in Nepal)

Revelations about the organisation Hami Nepal clarify the external direction behind the riots. Western outlets themselves reported that Hami Nepal played a leading role in organising the demonstrations that set fire to the parliament and forced the Prime Minister’s resignation. The group presents itself as a local non-governmental organisation but openly lists partnerships with American corporations, including Coca-Cola, and boasts of links to projects financed by the National Endowment for Democracy such as the “Free Tibet” campaign. Its website carries the logo of Students for a Free Tibet, a body named in NED’s own disclosures as a funded partner. This connection underlines how networks presented as grassroots charities or civic groups operate as vehicles for foreign political projects, embedding external agendas within local protest movements.

The wider strategic context is decisive. Nepal borders China and sits within India’s traditional sphere of influence. Both Beijing and New Delhi are pursuing closer cooperation under the framework of the emerging multipolar order. American planners view the Himalayan state as a critical piece of terrain for disrupting Chinese connectivity projects and complicating Indian strategic autonomy. Colour revolutions serve as cheap instruments for producing political disorder, denying stability to governments inclined toward policies inconsistent with US interests. The current operation in Nepal follows unrest in Indonesia, a state which has resisted American demands to adopt hostile positions toward Beijing. The use of identical tactics across countries within weeks indicates a coordinated regional campaign.

Independent analysts have consistently warned that the National Endowment for Democracy, despite its benign sounding name, operates as a cover for the Central Intelligence Agency’s political warfare programmes. While the organisation presents itself as a promoter of civil society, its budget and operations are aligned with US foreign policy objectives. When Washington desires destabilisation of a government, NED-supported groups suddenly emerge at the forefront of protests, supplying money, training, communication channels, and international media amplification. The young demographic used as the shock troops of unrest rarely comprehend the geopolitical context. They are mobilised with slogans of freedom and democracy while serving as instruments of foreign interference.

The evidence matches this pattern with precision. The average age of demonstrators, the rapid adoption of protest symbolism, the immediate targeting of parliament and residences, the resignation of the head of government, the international media framing of events as youthful resistance to digital censorship, all align with past operations funded by Washington. No serious analyst can mistake this sequence for domestic, organic protest. It is an imported strategy tailored to Nepalese conditions but designed and financed abroad.

The consequences for Nepal are severe. A government forced to abandon regulation of its own information space is one stripped of sovereignty. A political class intimidated into resignation under street violence is one subordinated to external powers. An army compelled to rescue ministers by helicopter reveals institutions under siege by forces they do not control. The immediate casualty figure of nineteen represents only the first wave of human cost. The longer term consequence will be political fragmentation, economic disruption, and polarisation of society between those aligned with Western narratives and those defending national independence.

Comparisons with other theatres reinforce this conclusion. In Ukraine, colour revolution operations directly paved the way for years of instability and war. In Hong Kong, unrest crippled the local economy until Beijing reasserted control. In Serbia and Georgia, successive governments installed through street protests became conduits for Western economic and military interests. Nepal now risks the same trajectory, where external funding networks displace national political processes and local populations are manipulated into undermining their own institutions.

The decapitation strategy applied in Nepal is accurate as description. In past decades the United States relied on direct military interventions to topple governments, from Iraq to Libya. The costs and consequences of those wars produced a shift toward more subtle instruments. Instead of cruise missiles and drone strikes, programmed youth movements now serve as the weapon of choice. The objective remains identical: remove independent governments and replace them with compliant elites. The method avoids the spectacle of invasion but achieves the same outcome through engineered chaos.

The lifting of Nepal’s social media restrictions already indicates partial success for Washington. American platforms regain access to the population, algorithms once again shape perceptions, and foreign influence networks resume operations. The resignation of the Prime Minister creates opportunity for installation of a leadership more aligned with US preferences. The prediction that an American-aligned puppet will be sworn in repeats patterns observed in Pakistan and Bangladesh. The direction of events supports that assessment. Once a government capitulates to externally directed street violence, it becomes difficult to restore independent policy without facing renewed upheaval.

The broader lesson is the urgent need for states within Asia to secure their information sovereignty. As long as communication infrastructures remain dominated by American corporations, governments will remain vulnerable to manipulation. Bans on non-compliant platforms represent a rational measure of self-defence, yet they provoke direct retaliation through colour revolution tactics. Multipolar institutions must therefore prioritise development of independent platforms, regulatory frameworks, and cooperative measures to insulate societies from Western information warfare. Without such measures, repeated cycles of destabilisation will continue to undermine emerging centres of power.

For Nepal, the path forward will be difficult. The damage inflicted on its institutions and the precedent of forced resignation weaken its capacity to resist external pressure. Rebuilding requires recognition of the forces at play, an understanding that the unrest was not a spontaneous movement of youth but a directed assault on sovereignty. Independent media, civil society groups not tied to foreign funding, and regional partners must assist in exposing the mechanisms of manipulation. Awareness is the first defence. Without it, populations will continue to be mobilised as foot soldiers for foreign agendas.

Events in Nepal must be understood not as isolated turbulence but as part of a regional strategy. Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal share the common feature of refusing to adopt Washington’s preferred policies on China. In each case, unrest followed swiftly. The consistency of timing, tactics, and outcomes points to a deliberate campaign. Analysts and policymakers across Asia must therefore coordinate responses. Recognition of colour revolutions as instruments of foreign policy is essential for building resilience. Without such recognition, each state will face destabilisation alone, while Washington and its allies exploit the resulting weakness. Taken together, these measures create friction for external orchestration without banning protest, dissent, or critical journalism… BRICS cooperation can turn ad hoc crisis management into a standing architecture that deters interference and stabilises politics across a contested region.

Unrest in Nepal mirrors the recent disturbances in Indonesia, where colour revolution methods were also visible. In both states, young protestors were mobilised quickly, imported cultural symbols were displayed to create instant recognition, and staged clashes with police were broadcast to international audiences. Indonesian documents had already shown evidence of coordination between local groups and foreign organisations receiving American funding, and the replication of the same tactics in Kathmandu suggests a broader regional campaign rather than isolated, localised protest movements.

The Nepal case shows how colour revolution methods can be applied repeatedly across different societies with only minor adjustments. Organisers rely on young demographics who are highly active online and less connected to established institutions, making them easier to mobilise through digital campaigns. Symbols taken from global entertainment act as unifying markers that give protests a ready-made identity. Social media platforms supply the means to coordinate gatherings, distribute instructions, and shape outside perceptions of the unrest. Local grievances are absorbed into these prepared templates, giving the impression of organic activism while serving external strategic goals.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment