Why Western Debt and Sanctions Lose Power Against New Blocs

The evolution of BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation has altered the global strategic balance in ways that analysts now consider irreversible. These blocs, taken together, represent over five billion people and more than half of global output in purchasing power parity terms, which marks a structural shift from the long dominance of the Atlantic economies. The figures now cited by independent economists place the combined GDP of BRICS and the SCO at around ninety five trillion dollars in PPP terms, out of a global total of one hundred seventy three trillion. This is not a projection but an established measure of present economic weight that underscores how far the global economy has moved since the 1990s when the G7 dominated with ease.

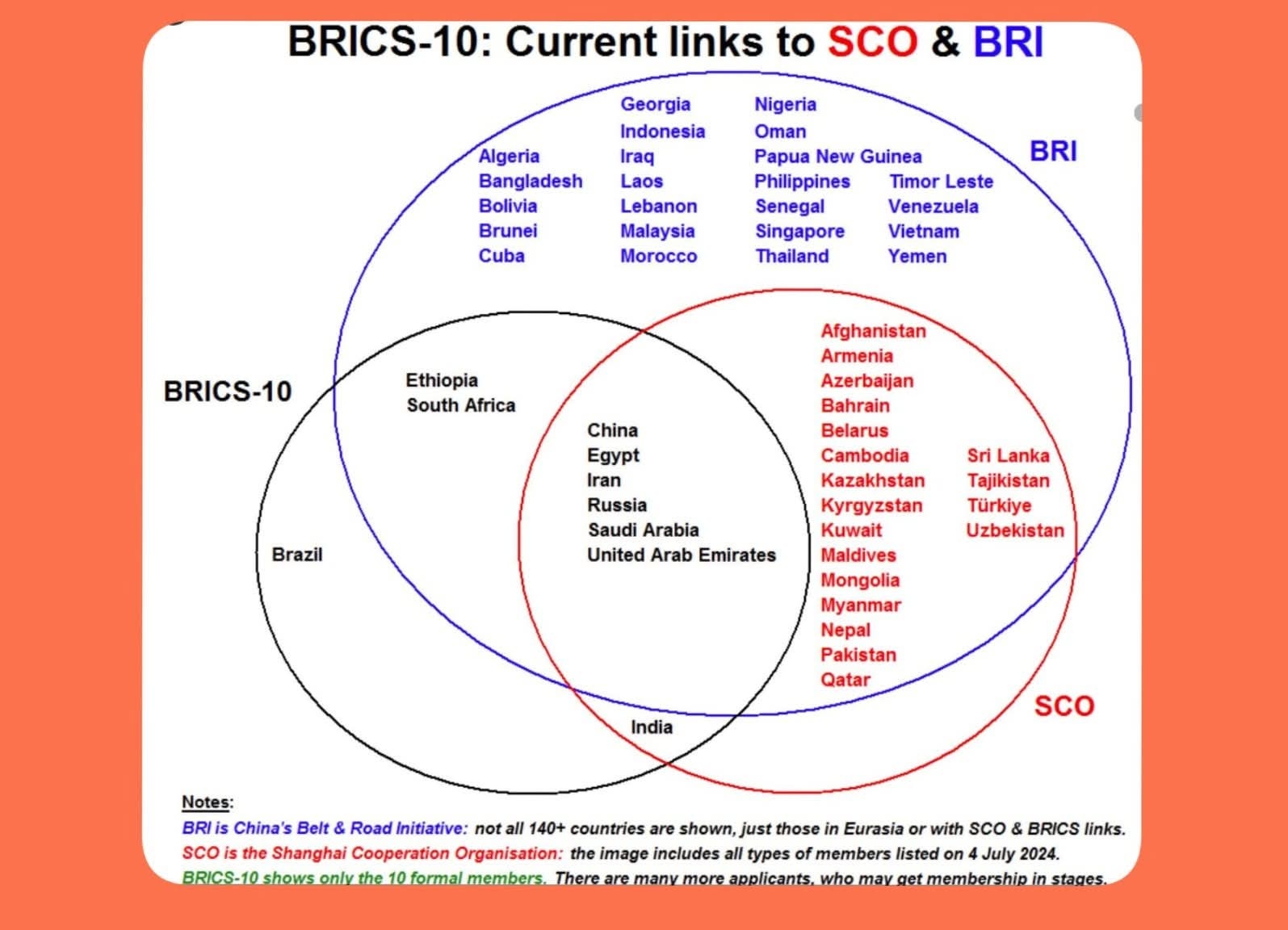

The pathway to this position began with a cautious process of regional cooperation that matured in the post Cold War years. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation emerged in the late 1990s as a mechanism to manage borders and coordinate counter terrorism in Central Asia. From that limited remit it has broadened into a platform for economic integration, infrastructure development, and dialogue between Eurasian states. Membership now extends beyond China, Russia, and the Central Asian republics to include India, Pakistan, and Iran, with dialogue partners ranging from Turkey to Egypt. This expansion shows the continuing attraction of institutions that can function outside the reach of Western dominated security and economic structures.

The momentum of enlargement reflects a structural logic. States with growing populations and resource endowments look for mechanisms that give them greater voice in setting the rules of trade and finance. The New Development Bank was created by BRICS as an alternative to the World Bank, designed to fund infrastructure with fewer political conditions. Its capitalisation remains small compared with the global financial institutions, but its symbolic role is significant. The use of national currencies in settlement, promoted in successive summits, is a practical expression of the same ambition to erode the dependence on the dollar.

The geopolitical ramifications are extensive. For Russia, the institutional backing of BRICS and the SCO provides a cushion against Western sanctions and diplomatic isolation. For China, the blocs extend the Belt and Road Initiative into wider political legitimacy and reduce reliance on Western controlled institutions. For India, the forums provide opportunities to secure development finance and trade access while maintaining strategic autonomy. For the Middle Eastern members, participation signals a hedge against reliance on Washington and a pragmatic bet on multipolarity. For African members, access means leverage in negotiations with international lenders and expanded investment options.

Security implications follow from the institutional weight of the SCO. While not a military alliance, its regular joint exercises, counter terrorism drills, and security dialogues create a framework of interoperability and trust building between member armed forces. The expansion of SCO membership to include nuclear armed states such as India and Pakistan further complicates the security architecture of Eurasia. Western strategists view the bloc with concern because it provides a platform where Russia and China can coordinate military narratives with the participation of other major states.

Economics remains the decisive dimension. BRICS members now account for a majority share of global energy production, with Russia, Iran, and the Gulf states controlling significant oil and gas reserves, while China and India dominate consumption growth. This energy leverage intersects with supply chains in technology and manufacturing, giving the bloc structural power in shaping global markets. The Economist Intelligence Unit has reported that the combined trade volume of BRICS has outpaced that of the G7, which shows the degree to which the economic centre of gravity has shifted.

The trajectory of the next five years points to further consolidation. Turkey has expressed interest in joining the SCO, and Mexico has been mentioned as a potential dialogue partner for BRICS. If such accessions occur, the population coverage of these blocs would approach seventy percent of humanity, and the share of global GDP could move towards sixty percent. Analysts at RAND note that the addition of middle income powers would deepen the political legitimacy of the blocs, while also introducing new tensions given divergent national interests.

The geopolitical consequences extend to the institutional balance of the United Nations. A greater coordination of votes by BRICS and SCO members in the General Assembly and other UN bodies reduces the capacity of Western coalitions to push through resolutions. African and Asian states that align with these blocs gain bargaining power in negotiations over development aid and climate finance. This trend is already visible in UNCTAD and WTO discussions, where bloc members advocate for reforms to trade rules that favour industrial development over intellectual property protections championed by developed economies.

One must also consider the technological and industrial dimension. China and India’s growing role in digital infrastructure, artificial intelligence, and space programmes brings advanced technology into the bloc’s portfolio. Russia and Iran provide defence industrial capabilities, while Brazil and South Africa bring agricultural and mineral resources. The technological partnerships now under discussion in BRICS summits include joint satellite projects, cross border data governance frameworks, and coordination on semiconductor supply chains.

The trajectory of de dollarisation deserves specific scrutiny. While the process remains partial, the political commitment of major economies to diversify settlement currencies has tangible effects. Russia and China already settle much of their bilateral trade in roubles and yuan. India has experimented with rupee based settlement mechanisms for oil purchases. Gulf members of BRICS have discussed pricing some energy exports in non dollar currencies. These moves have limited effect on the global role of the dollar so far, but the trend is consistent and creates cumulative erosion of its dominance.

The rise of these blocs signals a shift from unipolarity towards multipolarity, with competing centres of gravity in global governance. The G7 once claimed legitimacy through its economic weight and technological superiority. Today, those advantages have narrowed or disappeared. G7 members now represent less than ten percent of the global population and under thirty percent of global GDP in PPP terms. Their leverage depends on finance, institutions, and military capacity, but these tools are less effective when alternative forums and financing channels exist.

The likely direction is towards a fragmented but functional multipolar system. BRICS and the SCO will not replace the UN, the IMF, or the World Bank, but they will provide alternative channels that reduce dependence on them. This diversification creates resilience for member states and reduces vulnerability to unilateral sanctions. It also introduces inefficiency into global governance, as overlapping institutions compete and duplicate functions. The long term outcome will be a more contested and transactional system in which rules are negotiated case by case rather than imposed universally.

The security architecture will likewise reflect pluralism rather than bipolar division. SCO exercises demonstrate growing military confidence, but the absence of binding defence commitments means that strategic autonomy remains the guiding principle. BRICS has no security mandate, but its political solidarity creates diplomatic cover that blunts Western pressure. The consequence is a more complex operating environment for NATO and the European Union, where deterrence must account not only for direct adversaries but also for networks of states that may provide political or economic cover.

Western elites face an existential challenge because the financial order that allowed them to extract wealth from the global south is breaking down. The post war system let Western states run high debts and absorb the resources of others through institutions and currency privilege, while wars periodically reset currencies and restored balance sheets at the expense of others. The use of fabricated threats, such as exaggerated drone sightings in Eastern Europe, creates a political climate for militarisation in Poland and Romania, while large scale bases planned in the Philippines show preparation for escalation in Asia. Russia, Iran, and China have anticipated this dynamic and hardened their economies and defences against attempts at encirclement. France’s withdrawal from the Sahel after decades of dominance has deprived it of resource access and contributed to wider economic malaise, showing the limits of the old model. Western states may look to cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, and central bank digital currencies to restructure debt and reassert control, but these tools cannot erase the erosion of confidence in their financial stewardship. BRICS members hedge with gold reserves, commodity trade, and settlement in national currencies, building mechanisms that prevent them from being drawn into cycles of Western debt repayment. The difference is stark: one side seeks war and financial reset to preserve privilege, the other builds alternative systems to shield against external liabilities. The outcome depends on whether Western escalation can overcome the growing resilience of the Eurasian and global south networks, but the structural balance suggests that attempts to restart the old order through global war are less likely to succeed than in the past.

The conclusion reached by most independent analysts is that the rise of BRICS and the SCO marks a permanent adjustment in the distribution of power. The blocs will face internal tensions and capacity limits, but their demographic, economic, and resource base guarantees them a central role in shaping the century ahead. The G7 and Western institutions will remain influential, but no longer decisive. The international system that emerges will be more fragmented, more regionalised, and more contested, but also more representative of the demographic and economic realities of the modern world.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

https://ko-fi.com/globalgeopolitics

Leave a comment