Foreign funding and digital platforms behind Nepal’s youth revolt

On 8 September 2025 the Nepalese government ordered the blocking of major social platforms including Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok after weeks of mounting criticism about corruption, governance, and elite capture of public institutions. The decision triggered immediate mobilisation across Nepal led primarily by young people who relied on alternative channels such as Discord servers, Instagram backups, Telegram groups, and VPN-enabled messaging to coordinate demonstrations and spread tactical instructions. Contemporary reporting from Reuters confirmed the mobilisation rapidly escalated into large street actions across Kathmandu, Pokhara, Biratnagar, and other major urban centres, leaving dozens dead and hundreds injured within five days of confrontations between protesters and security forces. The state’s reliance on mass blocking measures rather than targeted enforcement created exactly the rallying incentive that young organisers used to accelerate their protest momentum and broaden their legitimacy.

At the centre of the mobilisation sat Hami Nepal, an organisation that had presented itself for years as a registered non-profit rooted in disaster relief and youth volunteerism. Public pages of the group describe early origins in earthquake response work before shifting toward broader civic activism. By mid-September independent reporting and photographic evidence placed its founder and senior leaders in meetings with political actors, including discussions over an interim cabinet following the resignation of Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli. That fact alone confirmed the transition of Hami Nepal from civic non-profit to active political broker in record time. This speed of transformation raised questions about how much infrastructure, funding, and training had already been built before the protests erupted.

Foreign donors, training programmes, and international non-governmental organisations created and sustained the networks that made rapid youth mobilisation possible. Public records show the National Endowment for Democracy maintains accessible listings of Asia regional grants demonstrating active programmes in Nepal across youth organising, civic engagement, and media development. These records, published annually, include recipients across South Asia, including Nepali groups engaged in transparency and anti-corruption work. The Freedom Forum and Accountability Lab, both registered in Nepal, publicly list their funding partners, many of which include foreign development agencies and private foundations. Similarly, the Committee to Protect Journalists, which has documented Nepali press issues for decades, publishes annual financial reports identifying institutional and corporate donors, many based abroad. These records establish a consistent pipeline of foreign funding, capacity building, and technical assistance connected to Nepali civic organisations.

Long-standing financial relationships and training programmes contributed to the capacity of youth organisations and civic groups in Nepal. The protests between 8 and 13 September involved tens of thousands of participants operating across multiple urban centres, demonstrating the effectiveness of these networks. External training programmes strengthened organisational skills and coordination, but the mobilisation on the streets was carried out by the protesters themselves. These programmes played a clear role in building protest capacity, providing structure and resources that enabled rapid and widespread action. Analysts can distinguish between the structural support created over years and the execution of tactical operations by local actors during the five-day period of demonstrations.

Empirical evidence supports two clear conclusions. First, the architecture of foreign civic funding in Nepal is large, multi-sourced, and has been maintained for years across different sectors including anti-corruption, press freedom, and youth mobilisation. This fact is easily confirmed by reviewing official grant lists, donor pages, and published financial statements. Second, digital technology now compresses mobilisation timelines in ways that public records cannot clarify. Platforms such as Discord and Instagram allow small groups of organisers to disseminate instructions to tens of thousands within hours, enabling rapid convergence of crowds, flash protests, and coordinated messaging. Al Jazeera’s reporting on the Nepal events documented precisely how encrypted and decentralised channels allowed dispersed groups to coalesce quickly despite state shutdowns.

Policy implications flow directly from these observations. Analysts and governments must stop treating the question of foreign involvement as a simple binary of guilt or innocence. The record shows structural influence through capacity building and donor support, but tactical causation over specific mobilisations remains harder to prove. Public policy therefore requires detailed mapping of where training, technical assistance, and funding connect into local infrastructures, rather than broad accusations. Transparency in donor reporting and contemporaneous disclosures from recipient groups would reduce uncertainty when protest waves generate rapid political outcomes. Without such transparency, every sudden mobilisation will trigger allegations of covert orchestration, fuelling cycles of suspicion and repression.

A second implication concerns state handling of digital platforms. When governments choose to impose sweeping shutdowns of popular social media without legal clarity or technical precision, they create immediate rallying incentives for disaffected groups. Protesters interpret shutdowns as proof of authoritarian intent, and organisers quickly adapt by switching to alternative platforms and VPN-enabled coordination. That dynamic was visible in Nepal where Discord and Telegram became central after Facebook and TikTok were blocked. Policy on digital governance therefore requires more than blunt shutdowns. It must integrate international standards on proportionality, due process, and the safeguarding of civic rights. Otherwise states risk accelerating mobilisation rather than suppressing it.

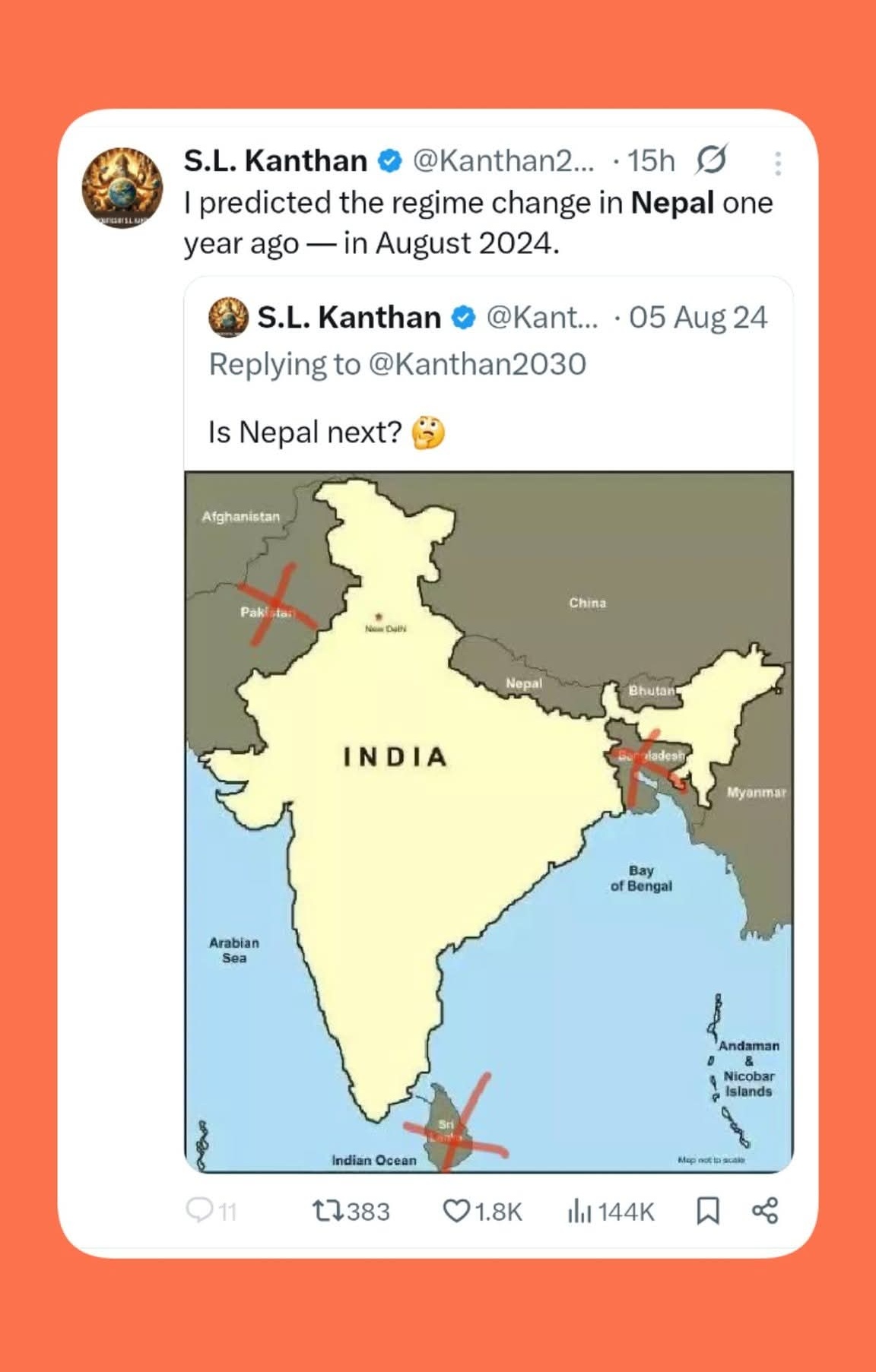

Comparative cases across South Asia confirm similar patterns. In Sri Lanka during 2022 the youth-driven Aragalaya protests forced the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa after demonstrators stormed the presidential palace. Yet within months Ranil Wickremesinghe, a veteran insider, took charge and signed a $3 billion IMF programme. The fiscal and legal architecture remained unchanged despite dramatic scenes. In Bangladesh during 2024 student protests escalated into violent clashes, leaving as many as 1,400 dead by United Nations estimates, only for entrenched security forces to reassert control. In Nepal during 2025 young people toppled a Prime Minister, but questions remain whether entrenched party elites will soon reassert themselves. These cases show how youth energy often achieves symbolic victories, but deeper structural levers of finance, military, and bureaucracy remain intact.

The Pakistani case of Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf further illustrates the dynamics of managed revolution. Khan’s movement, which electrified Gen Z from 2011 onwards, converted social media enthusiasm and youth rallies into electoral power by 2018. Yet after Khan’s ouster in 2022, the state apparatus moved systematically to neutralise PTI’s youth machine. Protests on 9 May 2023 triggered widespread crackdowns, mass arrests, internet throttling, and restrictions on TikTok and Twitter. Youth who once symbolised national renewal were recast as security threats. In hindsight PTI looks like a safety valve experiment in which youth enthusiasm was permitted to reach power temporarily before being tightly constrained once it conflicted with entrenched interests. This reading mirrors the Nepalese case where youth-driven mobilisation achieved an interim political victory but faces uncertain consolidation.

The global parallels reinforce the pattern. Hong Kong’s protests in 2019 and 2020 mobilised millions of young people but were dismantled by a National Security Law and subsequent mass arrests. The Arab Spring in 2011 demonstrated youth capacity to ignite revolts across Tunisia, Egypt, and beyond, yet militaries and monarchies dictated final outcomes. In Chile between 2019 and 2023 youth activism achieved a referendum to draft a new constitution, only for voters to reject two consecutive drafts, leaving institutional change unrealised. These examples underscore that youth passion and digital mobilisation ignite upheaval but rarely build durable institutions capable of sustaining reform.

The interim leadership was chosen by a vote conducted inside a dedicated Discord server whose membership comprised thousands of self-identified youth activists, volunteers, and sympathisers drawn from nationwide digital and offline networks. Contemporaneous reporting lists varying membership totals for that server, with some accounts noting figures near seven thousand and other accounts reporting substantially larger enrollments for channels identified as the “Youth Against Corruption” community hubs where polls and votes were held. Key questions therefore concern the constituent nature of that online body, specifically who controlled membership lists, how moderators validated votes, what procedures governed candidate nomination, and how offline organisers linked into the server’s governance mechanisms. The selection emerged after sustained street mobilisation, with organisers using moderator-led polls and internal consensus processes inside the server to identify a representative acceptable to protesters and state interlocutors for interim leadership. Comparative precedent shows the stakes clearly; Sri Lanka’s 2022 Aragalaya demonstrates how a popular uprising can be absorbed into fiscal programmes and rescue packages negotiated with international lenders and domestic elites. After that revolt, multilateral financing and debt restructuring anchored new policy directions and created channels through which external financing influenced governance choices and elite patronage arrangements. Nepal’s digital selection therefore requires immediate scrutiny of representativeness, verification, and post-selection institutional design, because procedural clarity is essential to prevent popular agency being displaced by managed patronage networks.

The Nepal episode illustrates the dual truth at the heart of contemporary protest politics. Foreign donors and capacity-builders have supported Nepali civic space for years, leaving a verifiable record in grant listings and donor reports. The sudden escalation of protests in September 2025 was carried out by thousands of Nepali youth acting with deliberate coordination and organisational skill, demonstrating a fully executed mobilisation that reflected initiative consistent wwith a high level donor blueprint and strategic planning across multiple urban centres. The story is one of external orchestration fueling agency of domestic actors, and there should be no denying of the influence of sustained foreign capacity-building from all documentary evidence of structured support. The groundwork is laid for both dimensions to coexist and must be recognised simultaneously.

For policymakers the immediate requirement is to demand and publish full, contemporaneous accounting of funding flows, partner relationships, and training activities connected to groups that lead mass actions. Transparent accounting would allow public debate, total scrutiny and openness. Simultaneously states must study the mechanics of digital mobilisation, understanding how small organiser cores can generate large street actions rapidly. Proportional responses are essential to safeguard public order without criminalising civic activism or resorting to blunt censorship that backfires. These two approaches, financial transparency and digital literacy, are necessary to stabilise democracies facing volatile youth mobilisation.

The long-term challenge remains whether youth-led movements can transition from episodic protest to institutional reform. Without structures, organisations, and policy capacity, youth energy risks becoming a permanent reserve army for symbolic upheavals that elders manage and redirect. If Nepali Gen Z wish to translate their September mobilisation into durable reform, they will need to construct accountable organisations capable of electoral strategy, legislative engagement, and policy development. Otherwise the pattern will repeat: dramatic uprisings followed by reassertion of entrenched elites and fiscal structures. Comparative experience across South Asia and beyond leaves little doubt about the consequences of failing to institutionalise protest gains.

The Nepal protests of September 2025 therefore must be studied not as an isolated eruption but as part of a regional and global pattern in which digital-era youth repeatedly confront entrenched institutions. The record shows foreign influence through funding and training, domestic agency through rapid mobilisation, and structural resilience of old elites who reassert control once the dust settles. The only path to break the cycle lies in building institutions that anchor youthful energy into sustained political reform. That conclusion may be blunt, but the evidence from Nepal and beyond leaves no space for ambiguity.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment