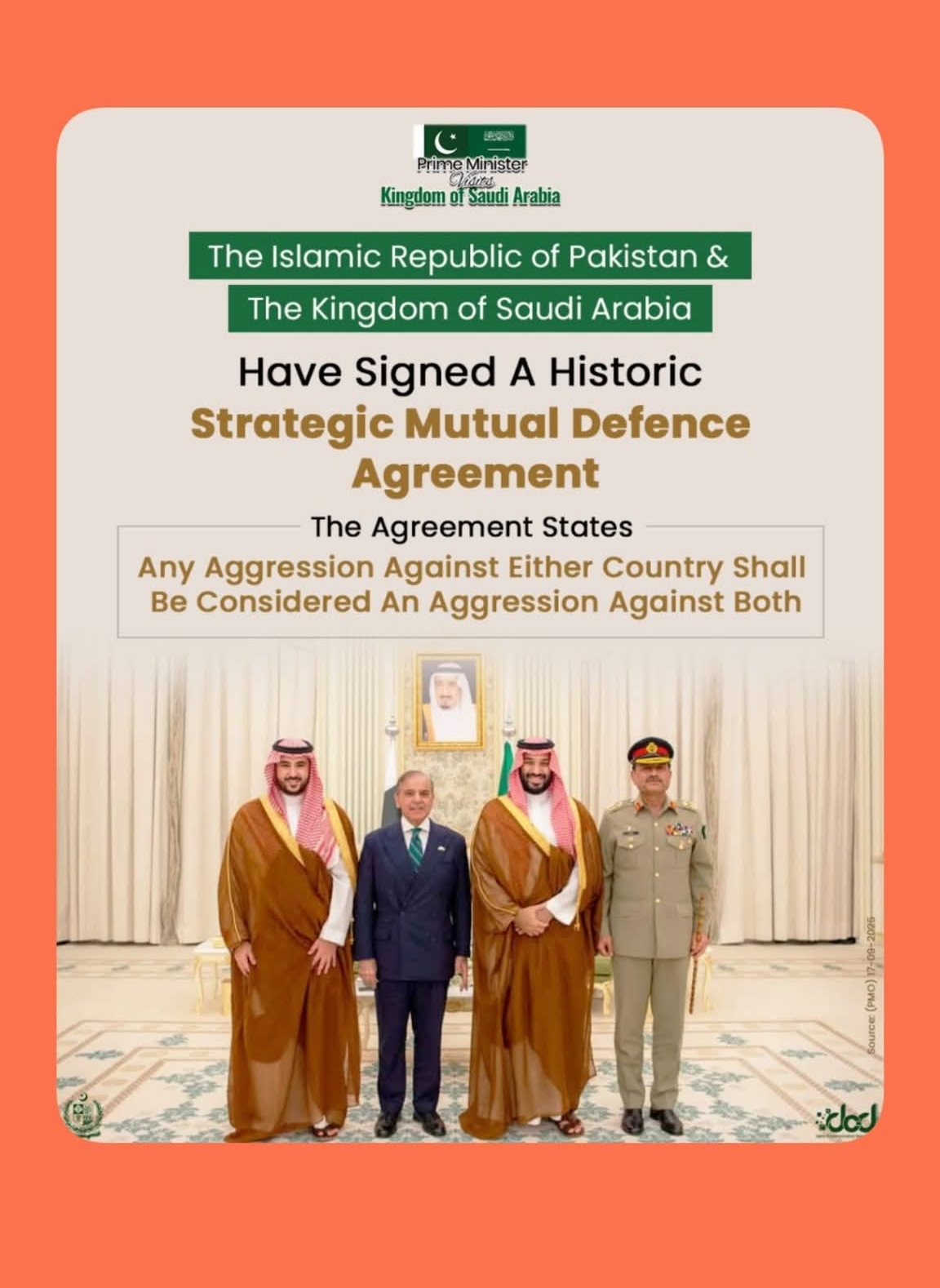

How a Saudi–Pakistan Defence Treaty Reopens Strategic Fault Lines in South Asia and the Gulf

Saudi Arabia and Pakistan signed a Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement in Riyadh on 17 September 2025, formalising decades of bilateral security cooperation that had until now been largely informal and episodic. The treaty sets out that any aggression against one party shall be treated as aggression against both, a clause that lends the pact strategic weight across the Gulf, South Asia and beyond. Senior Saudi officials briefed reporters that the agreement covers “all military means,” phrasing that Riyadh left deliberately open, while Pakistan’s defence minister publicly stated nuclear weapons were “not on the radar.” The ambiguity remains important, because it invites speculation about the possibility of Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent casting an indirect shadow over Saudi territory.

The pact comes after months of acute regional insecurity. On 9 September, Israel launched a targeted strike in Doha that killed Hamas officials and unsettled every Gulf capital. Leaders interpreted the incident as evidence of Israel’s reach and as a sign of fragile external guarantees. Gulf rulers have grown accustomed to an American presence that underwrites their survival, but repeated shocks since 2019, from Iranian missile and drone attacks on Saudi oil facilities to the Israeli raids in the heart of the Gulf, have raised doubts about Washington’s willingness to respond in a timely and decisive manner. According to regional security commentators at the Emirates Policy Centre and independent Saudi scholars, the pact with Pakistan should be understood as a hedge against that waning confidence, as much as a military agreement in its own right.

Pakistan carries unique credibility in this context. The May 2025 crisis with India featured four days of air and ground clashes in Kashmir and across the international border, with Islamabad claiming effective deployment of Chinese-built J-10C fighters armed with PL-15 long-range missiles. The episode drew commentary from military analysts at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, who noted the tactical shift in South Asia once Pakistan deployed modern Chinese platforms at scale. The Pakistani air force reported that it achieved favourable kill ratios in the exchanges, while India insisted the outcome was inconclusive. Whatever the operational reality, the confrontation confirmed that Pakistan retains an ability to impose costs on a conventionally superior adversary, and it reinforced its deterrent reputation. Gulf leaders are attentive to such demonstrations. They have trained officers in Pakistani academies for over half a century and relied on Pakistani troop deployments during critical moments such as the 1969 Saudi-Yemen border clashes and the 1979 Grand Mosque crisis.

For decades the security relationship has operated on a transactional but enduring basis. Thousands of Saudi officers trained in Pakistan, and Pakistani pilots flew Saudi aircraft during earlier Arab conflicts. In return, Saudi Arabia provided financial assistance during Pakistan’s sanctions periods in the 1990s and supplied deferred oil payments in later financial crises. This history sustains the pact announced in September. Yet this is the first time the relationship has been formalised into a treaty framework with explicit obligations of mutual defence. Think tank assessments from King Faisal Centre for Research and Islamic Studies emphasise that codifying this understanding transforms what was a flexible partnership into a binding security commitment with long-term implications.

The nuclear dimension dominates external perceptions. Pakistan insists its nuclear doctrine remains India-specific and strictly for national survival, not for export to third countries. The doctrine has been reiterated since 1998, and officials have argued that credibility depends on avoiding ambiguity about its scope. However, by signing a pact with Saudi Arabia under the language of “all means,” Islamabad risks creating the impression that Riyadh now sits under a Pakistani deterrent umbrella. Analysts at the Carnegie Endowment and the Centre for Strategic and Regional Studies in Islamabad point out that even if no warheads are transferred, the perception alone could spark strategic recalculations. Iran, which maintains tense relations with both Riyadh and Islamabad, would see the pact as a potential encirclement move. Israel, with proven reach into Gulf territory, would adjust contingency planning to consider Pakistani involvement. Washington would see it as an erosion of the nuclear non-proliferation regime, particularly in a context where the United States has invested heavily in security assistance to Israel since 2023.

Another layer to the Saudi–Pakistan pact lies not in the Gulf but further north, in Afghanistan. The mention of Bagram airbase by former U.S. President Donald Trump, seemingly out of the blue, points to a geographic reality that connects these developments. Bagram, located just north of Kabul and roughly 200 kilometers from Pakistan’s border, was once the hub of America’s military presence in Afghanistan. Since Washington’s chaotic withdrawal in 2021, the facility has symbolised both the abrupt end of U.S. influence and the enduring strategic value of Afghanistan’s terrain. Its proximity to Pakistan means that any renewed attention to Bagram, whether rhetorical or operational, signals outside powers are again thinking about Pakistan’s role in the region’s nuclear and security balances.

For Riyadh, this geography matters. A Pakistani deterrent implicitly tied to Saudi defence is embedded in a regional arc that includes Afghanistan’s uncertain security order, Iran’s western frontier, and Israel’s long-range strike planning. Trump’s invocation of Bagram can be read as a reminder that the infrastructure for power projection into South and Central Asia has not disappeared, only changed hands. Whether as a veiled warning to adversaries or as an invitation for allies to consider alternate staging grounds, the reference underscores that Afghanistan still sits at the crossroads of Middle Eastern and South Asian security dynamics. In this sense, the Saudi–Pakistani pact may is a projection beyond bilateral defence and how external actors recalibrate their strategies in a post-American Afghanistan.

This renewed U.S. push to reassert itself at Bagram, even rhetorically, also creates acute risks for Pakistan. Trump’s framing of the base as valuable because of its proximity to China’s nuclear sites links Afghanistan directly to U.S.–China confrontation. Any attempt to re-enter Bagram, short of outright reoccupation, would require Pakistani cooperation, through air corridors, intelligence sharing, or logistical facilitation. Once Islamabad enables signals or strike infrastructure, it inherits both the targeting and coercion that come with it. The memory of the Badaber listening post of the 1960s, when “temporary” permissions hardened into semi-permanent footprints and Pakistan became the lightning rod for retaliation, looms large. The fear is that history could repeat itself under new global conditions, this time with China as the central actor.

The China dimension makes the stakes higher than before. Beijing would interpret any Pakistani role in enabling Bagram-linked operations as alignment with Washington against its western frontier and against CPEC infrastructure nodes in Gilgit-Baltistan, Gwadar, and Kashgar. That perception would trigger political and economic blowback precisely when Pakistan’s financial solvency depends on Chinese loans and investments. Iran and Afghan authorities would likewise read such facilitation as a hostile alignment, shrinking Pakistan’s diplomatic room and exposing it to regional retaliation. The prudent course for Islamabad is to draw bright red lines now: no foreign basing, no covert lily pads, and no combat or ISR overflights disguised as temporary arrangements. Air corridors are sovereign, not entitlements, and clarity communicated in advance to Washington, Beijing, Tehran, and Doha is essential to prevent misreadings that could escalate into crises.

The regional timing matters as Saudi Arabia is pursuing a dual strategy of hedging between traditional Western partners and rising Asian powers. China has inserted itself into Middle Eastern diplomacy since brokering the Saudi-Iran rapprochement in 2023. President Asif Zardari’s September visit to Chengdu, where he toured Chinese fighter production facilities, highlighted the growing depth of Sino-Pakistani defence collaboration. Aviation experts writing in Janes Defence Weekly noted that Pakistan has now positioned itself as the primary foreign showcase for China’s next-generation platforms. For Riyadh, linking its security framework with Pakistan indirectly strengthens China’s relevance to Gulf security. Chinese analysts at Tsinghua University and the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies argue that the pact is a quiet victory for Beijing’s efforts to chip away at US monopoly over Gulf defence architecture.

India’s calculus has been disrupted as well. The defence pact places its two most important Gulf partners, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, in potentially closer alignment with Pakistan. India remains a vital economic partner for Riyadh, with millions of Indian expatriates in the Kingdom and extensive energy trade. Yet strategic analysts in New Delhi, including voices at the Observer Research Foundation, warn that India cannot ignore the symbolic weight of a defence pact that names Pakistan as Saudi Arabia’s mutual defender. India may seek to offset this by accelerating its security relationship with Israel, expanding trilateral exercises with the US and Japan under the Quad framework, or by strengthening naval partnerships across the Indian Ocean. Senior Indian officials have already announced that they are “studying the implications,” but private commentary in Delhi’s policy circles makes clear that pressure to respond will mount quickly.

The United States faces a multi-layered challenge. Washington has long opposed any moves that suggest nuclear collaboration between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. During the Obama and Trump administrations, officials warned Riyadh against seeking nuclear capabilities outside internationally accepted frameworks. Now, with Israel engaged in continuing conflict in Gaza and the US already criticised for its massive war financing to Tel Aviv, the prospect of a parallel security bloc emerging with Pakistan at its core will alarm American policymakers. Think tank voices at the Hudson Institute and the Quincy Institute both stress that Washington must decide whether to reassert direct guarantees to Gulf allies or risk losing influence to rising actors. Either course involves costs, and mistrust in Washington’s reliability after its handling of Afghanistan and Syria remains a live factor in Riyadh’s calculations.

Iran’s likely response is equally complex. Tehran maintains an adversarial relationship with both Riyadh and Islamabad, though it has avoided direct conflict with Pakistan in recent years. Analysts at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv and at Chatham House in London note that Iran will interpret the Saudi–Pakistan pact as an attempt to neutralise its missile and drone advantage. If Iran believes Riyadh might benefit from a Pakistani nuclear umbrella, its own Revolutionary Guard planners could adjust doctrines to increase reliance on asymmetric escalation, cyber strikes, and proxy deployments. This raises the risk of further instability in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria, where Iranian-linked groups maintain presence.

Inside Pakistan, the pact has produced mixed reactions among experts and commentators. Advocates highlight the prestige of formal recognition as a Gulf security guarantor and the likelihood of renewed financial flows from Saudi Arabia at a moment of dire economic difficulty. Pakistan remains under heavy external debt, reliant on IMF programmes, and burdened by power sector arrears that choke industrial recovery. Critics, including independent analysts writing for Dawn and Business Recorder, argue that overextension in foreign commitments risks aggravating domestic instability. They point to political fragmentation, an emboldened extremist network, and a deteriorating law-and-order situation in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as signs that Islamabad lacks the internal stability to project reliable external defence guarantees.

The pact highlights Pakistan’s enduring “balancing dilemma.” Islamabad seeks relevance by leveraging military strength, yet its economic fragility undermines long-term sustainability. The country has accepted Saudi loans and deferred oil payments many times before, but binding itself to mutual defence obligations requires more than financial assistance. Sustained deployments, intelligence integration, and military modernisation demand resources that Pakistan currently lacks. Defence economists at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute calculate that Pakistan’s defence spending already absorbs over 17 percent of public expenditure, crowding out social services and infrastructure. Adding an open-ended Gulf commitment would exacerbate fiscal stress and risk repeating cycles of debt dependency.

Independent Pakistani voices caution that the nuclear narrative must remain unambiguous. The doctrine was always declared as India-specific, framed as a last resort to ensure national survival. Diluting that clarity by tying it indirectly to Gulf defence risks inviting scrutiny from the International Atomic Energy Agency and from Western non-proliferation regimes. Scholars such as Pervez Hoodbhoy have long argued that Pakistan’s credibility on the nuclear issue depends on transparency and doctrinal consistency. Linking it to geo-economic bargains would undermine decades of hard-fought legitimacy.

For Saudi Arabia, the deal represents continuity in hedging. Riyadh has always diversified partners, from close US ties to defence acquisitions from Europe, and more recently to exploratory arrangements with China and Russia. Adding Pakistan deepens that hedge while drawing on a proven partner with direct battlefield credibility. Yet ambiguity over nuclear dimensions will complicate Riyadh’s diplomacy with Washington and Tel Aviv, both of which retain central importance for the Kingdom’s economic and technological ambitions.

Strategically, the pact raises questions about regional stability. Ambiguous defence commitments often create more danger than clarity, because they invite miscalculation. Analysts at RAND and the International Crisis Group argue that the most dangerous escalations in history occurred when states misread each other’s commitments and red lines. If Iran or Israel doubt the limits of Pakistani involvement, they may strike pre-emptively in a crisis. If Pakistan overestimates Saudi willingness to provide financial cover, it may find itself exposed in prolonged conflict. Clarity, not ambiguity, reduces risk.

The prudent course would involve public and verifiable clarification of what the pact covers, particularly on the nuclear issue. Mechanisms for crisis communication between Riyadh, Islamabad, Tehran and Tel Aviv would also reduce risk of inadvertent escalation. China, as a key partner for Pakistan and a growing actor in Gulf affairs, could play a role in creating such frameworks, while Washington retains the leverage to demand assurances through its Gulf military presence.

The Saudi–Pakistan defence pact is more than a bilateral arrangement. It represents a shift in regional security architecture, one that reflects declining confidence in traditional patrons, rising reliance on Asian partners, and the willingness of vulnerable states to seek ambiguous guarantees when threatened. For Pakistan, it offers prestige but carries risks of overextension, economic strain, and doctrinal confusion. For Saudi Arabia, it signals independence but risks further complicating its relationships with indispensable Western partners. For the wider region, it raises the probability of miscalculation and escalation at a time of already acute instability.

The choices made now will determine whether the pact becomes a foundation for new security arrangements or a catalyst for conflict. Both Riyadh and Islamabad must balance ambition with restraint, and both must resist the temptation to inflate commitments beyond what can be credibly delivered. States across the region and beyond will respond not to rhetoric but to clarity of doctrine, reliability of partners, and sustainability of commitments. Those principles, if followed, could prevent an ambiguous defence treaty from becoming the trigger of a wider war.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment