How Russia and China are redrawing trade corridors and outflanking Western containment

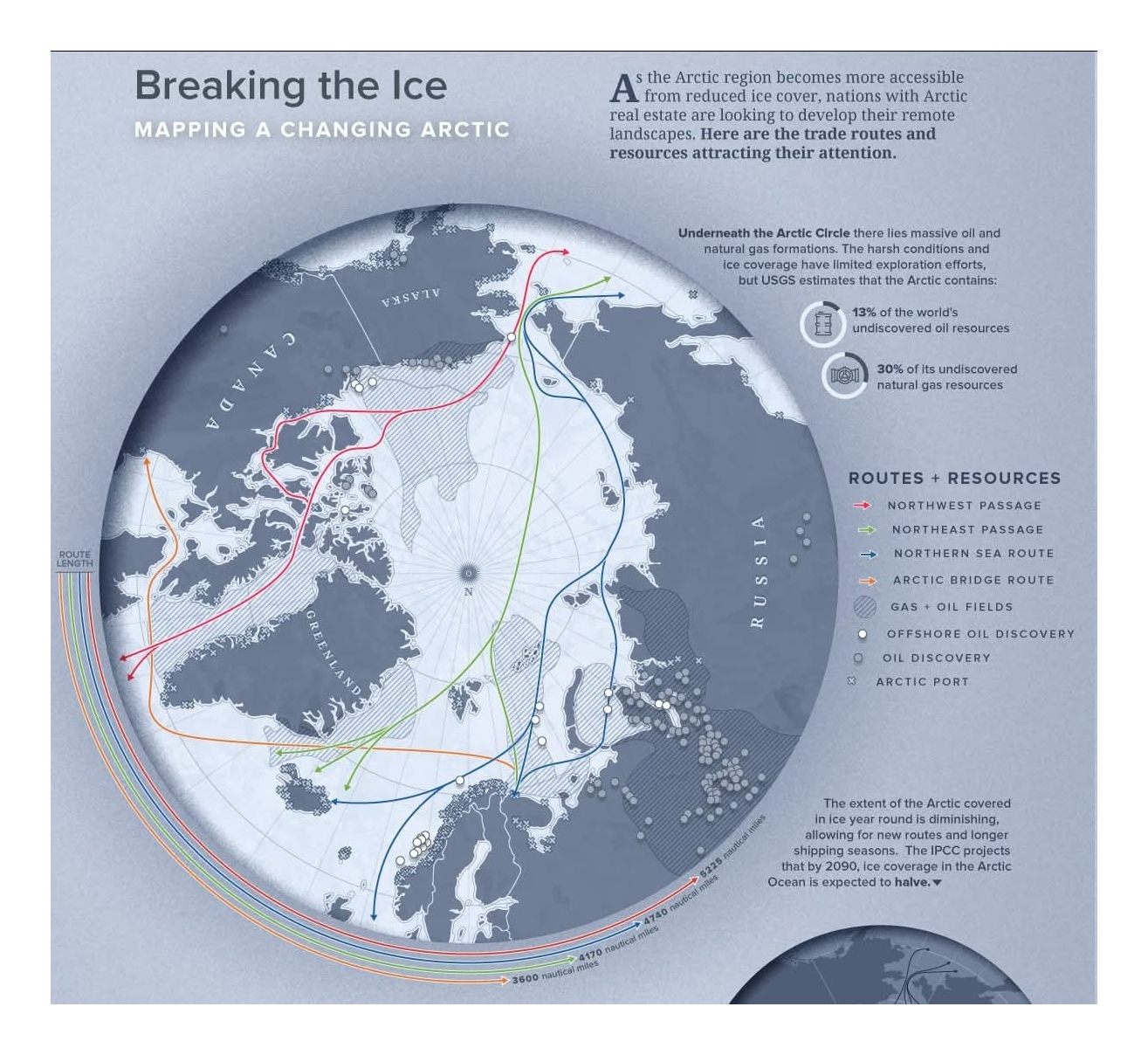

The Northern Sea Route now functions as a strategic artery reshaping Eurasian trade and power projection, and the material changes beneath that statement demand careful, evidence-based scrutiny. Melting sea ice lengthened navigable seasons and reduced transit times in some corridors, encouraging operators and states to trial new services and to invest in infrastructure that supports reliable commercial navigation. Satellite records show Arctic ice extent hitting record low maximums in 2025, and those physical changes have translated quickly into altered shipping patterns and expanding commercial interest in the route that runs along Russia’s Arctic coast.

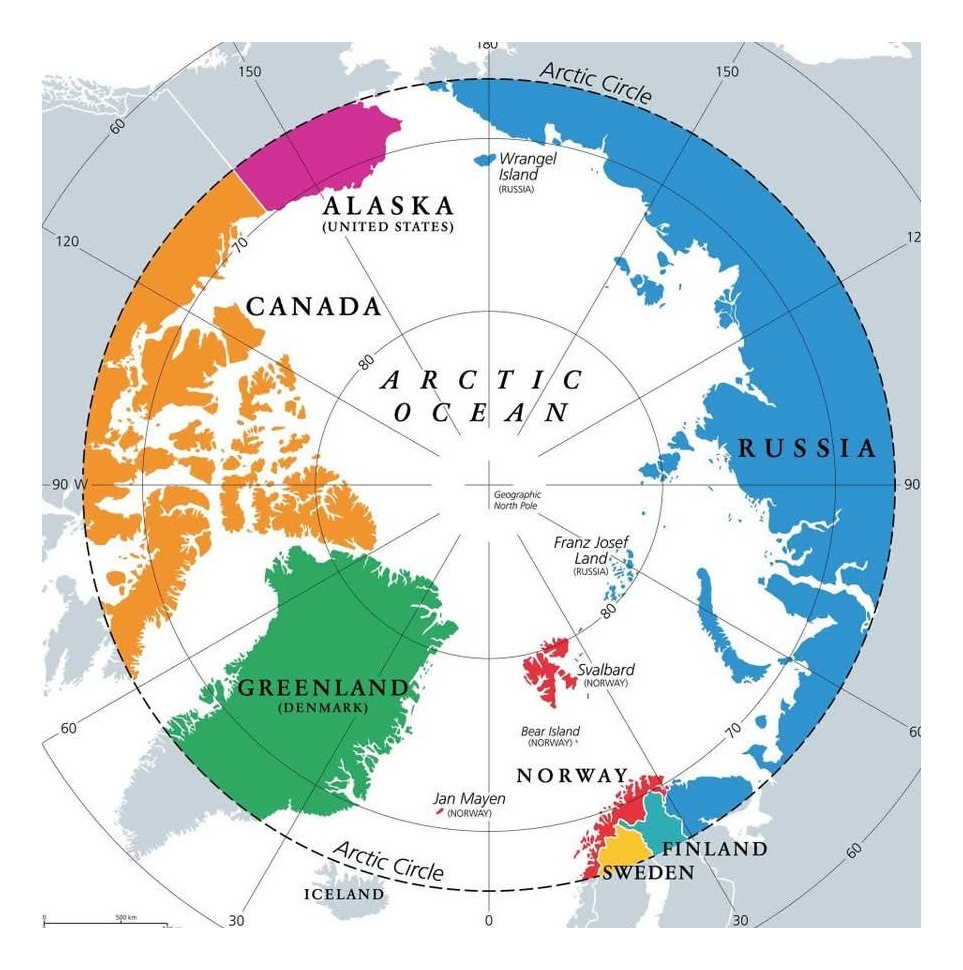

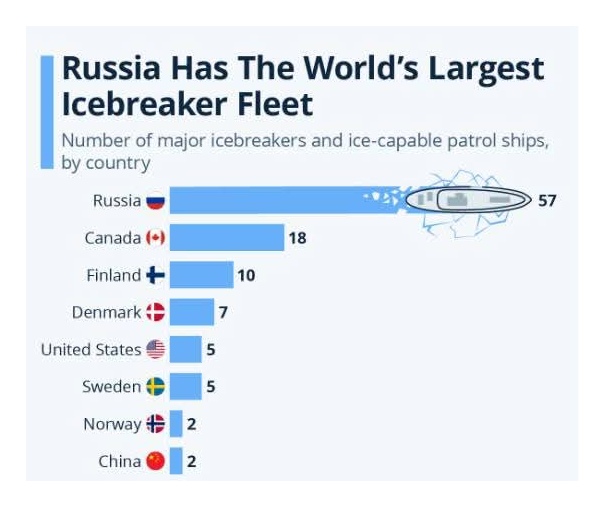

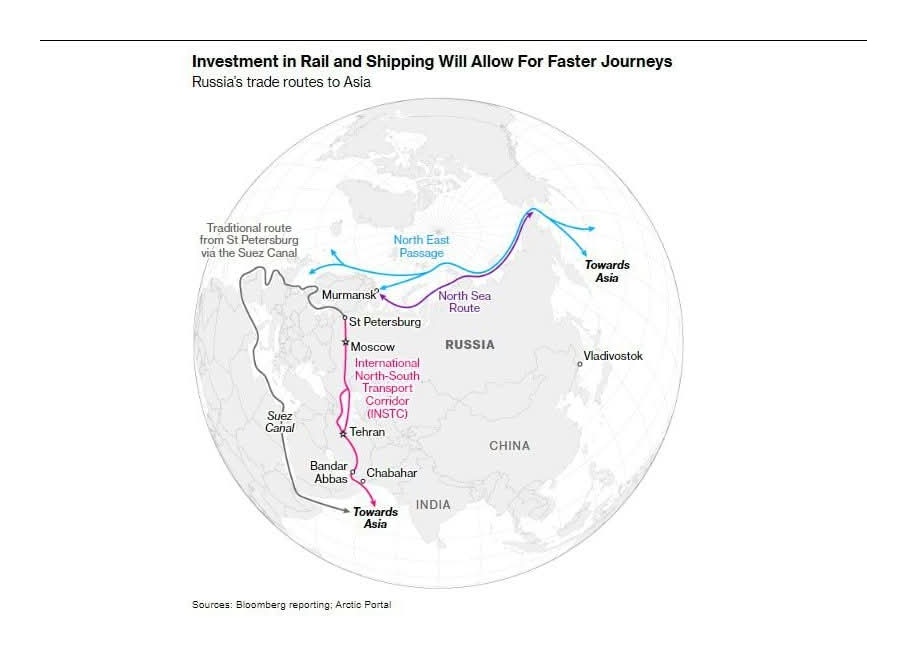

Russia planned and built for an Arctic opening long before commercial traffic increased, and that preparation explains its present advantage. The Russian state controls the largest share of coastline bordering the NSR, has invested in port modernisation at Murmansk and other hubs, and continues to expand state services for navigation, rescue, and environmental monitoring that underpin regularised shipping. Rosatom and state operators now claim operational oversight of ice reports, traffic control and merchant support along the corridor, and their programme of nuclear and conventional icebreaker construction remains unmatched by any single rival.

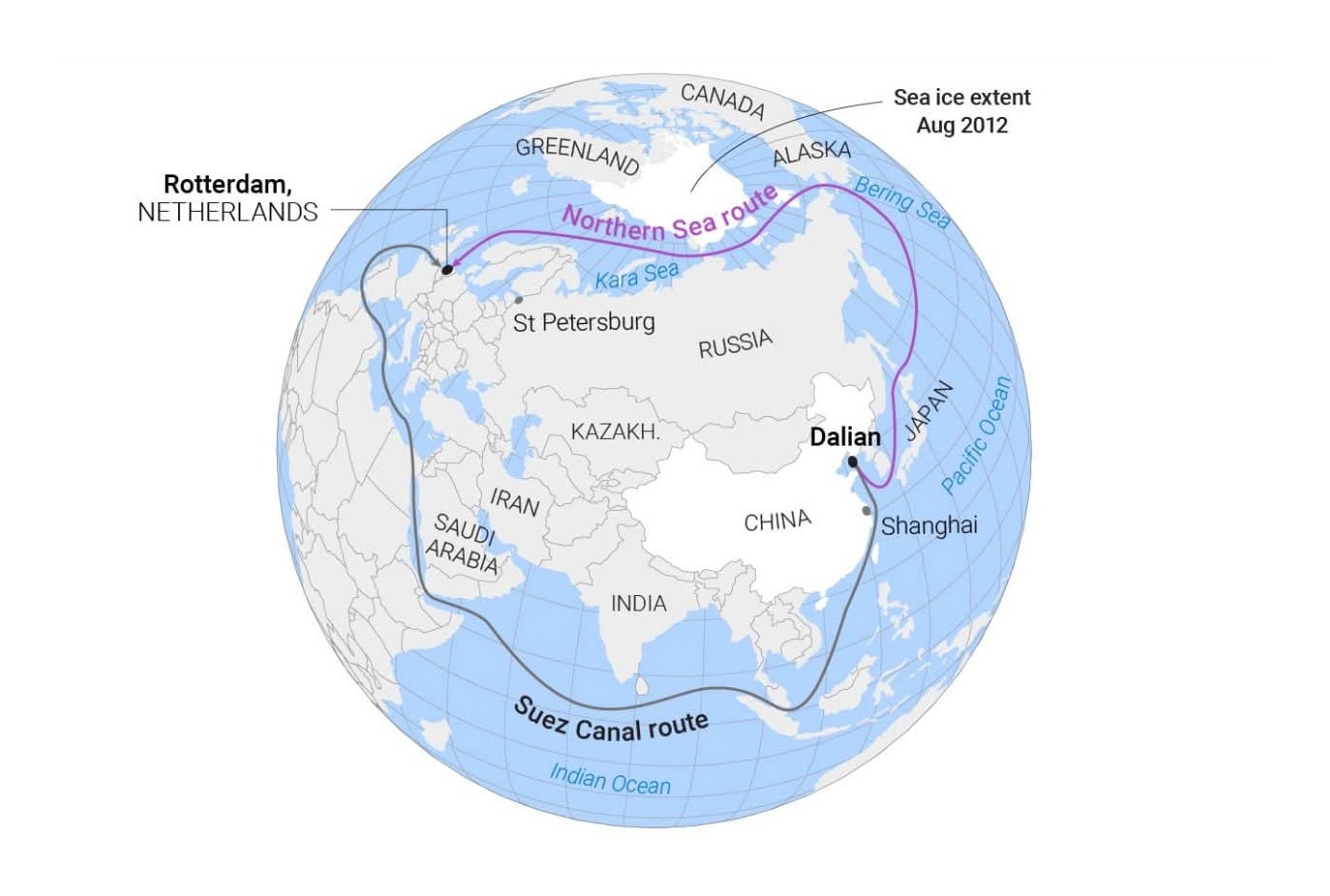

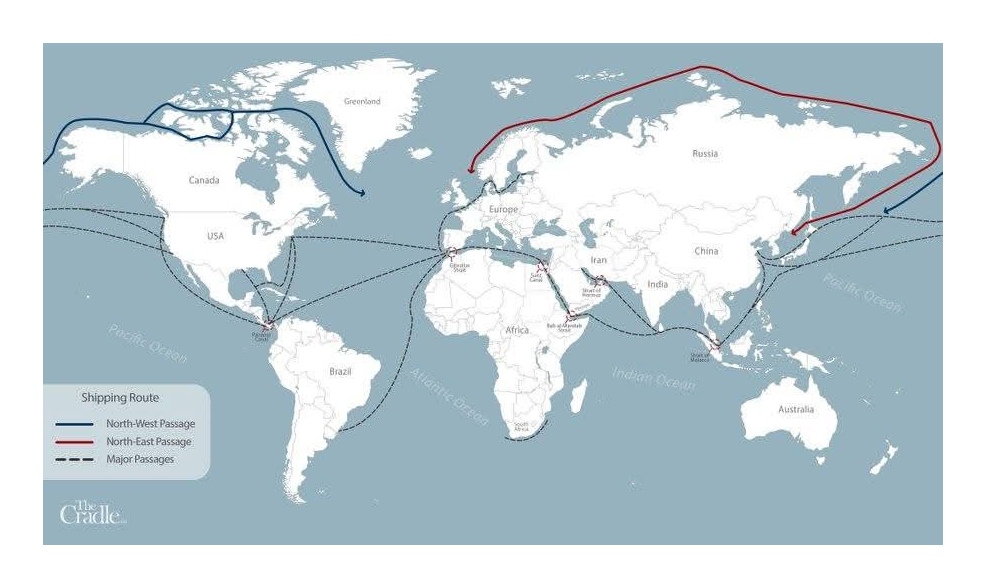

China is sending a container ship to Europe via the Northern Sea Route for the first time. The Istanbul Bridge, with a capacity of 4,890 TEU, will sail from Ningbo Zhoushan on September 24 and is expected to arrive in Felixstowe on October 10. The voyage will also include stops in Qingdao, Shanghai, Ningbo, Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Gdansk. This route, which passes these Arctic waters, will cut the journey time from the usual 40 days via the Cape of Good Hope to just 18 days. According to Chinese state media, the move marks a shift in how goods from China may reach European markets in the future. China’s role balances dependency with commercial appetite, and Beijing’s strategy operates through finance, shipping capacity and demand rather than overt Arctic sovereignty claims. China declared itself a “near-Arctic state” in its 2018 white paper and has pursued Polar Silk Road initiatives to knit northern shipping into wider Belt and Road economics. Chinese carriers and logistics firms now seek seasonal NSR services because shorter voyages for certain goods reduce fuel use and lead times, and Chinese energy demand underwrites large Arctic gas and LNG contracts with Russian producers such as Novatek and other companies operating in Yamal and Gydan. Those commercial links tie Beijing’s demand for hydrocarbons and raw materials to a corridor that runs under Moscow’s regulatory control.

The practical effects of that commercial logic now appear in concrete shipments and routes. In 2025 several container services announced inaugural voyages via the NSR, offering transit times roughly half those of the Suez for selected north-bound and west-bound services, and cargoes of LNG and oil have moved seasonally along the route to China using high ice-class tankers. Sanctions and political friction have not prevented deliveries of Arctic LNG to China, and recent transits show that regulated, state-backed operations can keep commerce flowing despite external pressure. Those shipments refract the strategic reality that economic necessity, shipping economics, and the presence of specialist ice-class vessels together make the NSR commercially viable in ways few Western planners expected.

Western responses have focused on containment through sanctions, deterrent signalling, alliance expansion, and attempts to build counter-capabilities, but those measures do not erase geography or existing infrastructure. NATO and allied strategy emphasises deterrence in the High North, and the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO altered the regional balance by bringing most non-Russian Arctic states formally into the alliance. Policy papers and alliance assessments now urge increased Arctic readiness and recommend investment in icebreakers, surveillance and logistics, but those recommendations face long procurement cycles and democratic oversight that slow delivery. The United States and partners have therefore pursued several tracks simultaneously including military signalling, sanctions against Russian projects, and initiatives to expand icebreaking capacity by multilateral procurement, while also attempting to deter secondary actors from servicing Russian Arctic projects. Those efforts can restrain some activity, but they cannot instantly replicate decades of Russian state investment.

Containment has been further complicated by indirect destabilising forces that pushed shippers away from southern routes and toward Arctic alternatives. Attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea in 2023–2024 reduced traffic through the Suez Canal and forced large container lines to reroute around Africa, adding time and cost to voyages and creating a business case for trialling more northerly seasonal options. Those attacks enlarged the market for alternative corridors by raising insurance costs, lengthening delivery times through southern passages, and increasing choke-point risk premia in global freight markets. The effect of such destabilisation runs counter to Western strategic aims when commercial actors seek secure, dependable options that bypass contested maritime zones.

Grey-zone activity at sea and along seabed infrastructure has produced a further layer of uncertainty that influences routing and state behaviour. Episodes of mysterious explosions against vessels near Russian ports, subsea cable damage in the Baltic, and shadow-fleet activity have led to increased inspections and naval exercises aimed at protecting shipping and critical maritime infrastructure. Those incidents have hardened Russian attitudes toward maritime security and provided pretexts for expanded naval patrols and anti-access measures in northern and adjacent waters. Governments now view commercial shipping not only as an economic flow but also as a venue for strategic vulnerability and therefore as a legitimate subject of national defence.

Russia adapts doctrine and force posture to the NSR as a dual-use strategic corridor where commerce and defence reinforce each other. The Kremlin reopened or reconstituted bases on archipelagoes such as Novaya Zemlya and Franz Josef Land, deployed layered air-defence systems and anti-ship capabilities, and conducted exercises meant to demonstrate control over the approaches to the NSR. Analysts across independent institutions observe that Moscow treats the route as sovereign infrastructure integrated into national logistics, and that integration includes naval assets, coastal batteries, and an icebreaker fleet that together protect and facilitate state-regulated passage for commercial convoys. Those measures change the military equation in the Arctic by moving the balance of power toward permanence rather than seasonal presence.

China’s posture in the Arctic remains careful and largely civilian, but its investments carry strategic weight that complicates Western leverage. Beijing prefers a commercial footprint and science diplomacy while avoiding direct military basing, yet its shipowners and energy companies finance and operate assets critical to NSR scaling. The more Chinese shippers and financiers normalise Arctic routes, the harder it will prove to isolate those flows through sanctions alone without imposing blunt damage on global supply chains. Scholars who study great-power integration emphasise that interdependence of this type reduces the political utility of sanctions and increases the disruptive cost of containment measures that do not account for commercial realities.

The political logic of proxy competition shaped Western policy around Eurasia, and the effort to prevent the seamless alignment of Russian geography with Chinese capital has included supporting Ukraine and contesting Chinese maritime reach in the Indo-Pacific. Those policies reduce the speed of integration but carry geopolitical costs. The case of the NSR shows how pressure in one theatre can accelerate cooperation in another theatre, because states under pressure tend to turn toward partners who offer practical, near-term solutions. Russian strategy therefore exploits Western pressure by offering China secure transport routes and energy supplies that reduce Chinese exposure to southern chokepoints. Independent analysts argue that such coupling has strategic durability precisely because strategic necessity supplies commercial reason.

The mechanics by which the NSR advances despite containment merit explicit listing because they run contrary to simple assumptions about policy levers and sanctions. First, climate change altered the baseline by extending navigable seasons and lowering operational costs for some voyages, creating an economic incentive for trials and new lines. Second, Russian state capacity in icebreaking, port services, and satellite and hydrographic monitoring reduces operational risk and enables regularised routes that private shippers will use. Third, Chinese demand for energy and faster logistics supplies a reliable commercial base for sustained traffic, and Chinese shipowners provide capacity for containerised services. Fourth, disruptions in southern routes and unstable near-term risk in chokepoints accelerate private actors’ willingness to test the NSR. Those four mechanisms operate together and explain why containment through sanctions and deterrence has failed to fully halt NSR development.

The geopolitics that develops around the NSR will not mirror a simple bipolar contest but will instead produce a layered landscape of mixed powers, contested jurisdictions, and differentiated dependencies. Russia will gain asymmetric leverage through control of regulatory regimes, port capacity and icebreaking services that other states must purchase for safe transit, whether in energy deliveries or container lines. China will gain shorter logistical corridors and a diversified route network that reduce its exposure to southern chokepoints and to adversarial trade restrictions. Europe will face a harder decision about whether to invest in northern infrastructure and naval capacity or to accept an altered trade geography that privileges northern hubs controlled by Russia, linked to Chinese capital. Those options involve profound tradeoffs between environmental politics, commercial interest, and strategic autonomy.

Western naval and diplomatic responses can slow parts of the NSR expansion, but reversing the corridor’s trajectory would require exceptional political will and sustained investment that so called democracies rarely mobilise quickly. Building a comprehensive icebreaker fleet, satellite constellation, rescue and environmental services, and a network of resilient northern ports would cost decades of steady funding and cross-party consensus. Democratic governance models (Private Oligarchy models) also impose environmental and indigenous consultation procedures that lengthen timelines, whereas Russian state capacity allows faster decisions and implementation in remote regions. Analysts who have compared private oligarchy-led and state-led Arctic strategies find that the latter can translate strategic patience into tangible infrastructure faster, altering the long-run balance.

A new threshold of contestation already appears in the operational choices of global shipping lines and insurers, who will segment services according to cargo value, insurance cost, and delivery urgency. High-value, time-sensitive shipments will favour shorter northern routes when seasonal conditions and icebreaker support make such passages predictable. Lower-value goods and bulk commodities will continue to use the Cape or Suez where economies of scale dominate. That segmentation produces durable commercial niches and consequent political leverage for the states that sustain the niche with public goods. Over time those niches can agglomerate into corridor economies anchored by specialised northern ports and logistics hubs.

The long-term consequences for global power are straightforward but severe. Control of an alternative Eurasian corridor weakens the leverage the United States and allies historically exercised through maritime chokepoints. Economic coercion loses margin when commodities and container flows can be routed outside traditional controls, and strategic influence will follow trade integration into what independent Eurasia scholars describe as a revived continental axis. The degree of that shift depends on scale; a year-round, high-capacity NSR supported by a robust icebreaker fleet and satellite surveillance would reconfigure strategic dependence, whereas a strictly seasonal and limited NSR will remain a niche corridor with constrained political effects. Current indicators show a steady trajectory toward higher capacity and normalisation as new services and state investments continue.

Policymakers who seek to preserve influence have three blunt choices, each with large costs that “democratic” politics must confront. They can replicate Russian state capacity by investing in their own icebreaking, surveillance and port infrastructure at scale. They can negotiate new legal and commercial frameworks that integrate Russian and Chinese participation under mutual guarantees, accepting a degree of commercial dependence while seeking regulatory checks. They can outsource resilience to private markets and risk pools, accepting a diminished direct role in governance while focusing on alternative levers of influence. Each path carries tradeoffs between strategic independence, economic exposure, and normative commitments to environmental and indigenous rights. Independent strategic studies conclude that hybrids and phased approaches will likely dominate policy responses.

The evidence thus far indicates that the NSR will become a permanent feature of Eurasian geography and diplomacy rather than a temporary curiosity. A combination of environmental change, Russian state capacity and Chinese commercial demand created conditions that sanctions and conventional containment struggled to reverse. Grey-zone threats and disruptions to southern routes accelerated commercial interest, and military investments hardened control over approaches to the corridor. Those facts together make the NSR an instrument of statecraft as well as a commercial option, with consequences for trade geography and strategic competition that will extend beyond the Arctic itself.

Independent analysts and university scholars warn that Western strategists cannot assume simple policy fixes will restore previous chokepoint dominance. Long planning horizons, credible investment commitments, and clear strategic prioritisation define the kind of response required, and democracies must choose whether to mobilise the resources necessary to contest the corridor materially. If they do not, the likely outcome will be a more multipolar system in which northern commerce and integrated Eurasian logistics shift strategic advantages toward Russia and its partners. Those outcomes will force hard choices in alliance management, trade policy, and defence posture across the coming decades.

The Northern Sea Route therefore stands as a practical pivot in twenty-first century geopolitics where geography, state capacity, commercial incentive and conflict interact. Understanding the NSR demands rigorous attention to these intersecting factors rather than to partisan narratives or rhetorical framing. The route will not vanquish southern passages overnight, and southern chokepoints will retain importance for many goods, yet the NSR will alter bargaining spaces, fuse energy and logistics politics, and produce a durable shift in lines of global influence if current trajectories continue. The policy challenge for Western so called “democracies” lies in reconciling commercial realities with strategic intent under “democratic” constraints.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment