The Advance of Post-Nation Control But First, They Need A Major War

For more than seven decades the United States has relied on a financial and military architecture built on the primacy of the dollar and control over oil flows. Independent economists such as Michael Hudson of the University of Missouri–Kansas City have shown that Washington’s ability to finance its military footprint abroad since the early 1970s was tied to the dollar’s role as a reserve currency and the recycling of US deficits through foreign central banks. That mechanism replaced the pre-1971 export surplus which once funded the overseas bases. By pushing other nations to hold dollar reserves instead of gold, Washington effectively monetised its global military spending. Hudson documented this inversion in his book Superimperialism, which has been used as a teaching text at US military academies despite being highly critical of policy.

Hudson’s analysis has been echoed by non-mainstream policy think tanks such as the Schiller Institute and the Valdai Club, which have documented the shift from export-led surplus to debt-financed power projection. As these bodies point out, Russia and China do not face the same constraint because they do not maintain hundreds of foreign bases and do not attempt to run an overseas empire. They fund their militaries domestically without needing to recycle deficits abroad. That difference underpins the current struggle over BRICS, de-dollarisation and alternative financial channels. It also explains why sanctions intended to isolate Russia after 2022 have not collapsed its economy. Russia was already operating without the dollar funding channel that sustains US power.

The use of oil as an instrument of coercion runs through a century of US foreign policy. Control over energy exports allowed Washington to shape the industrial capacities of allies and adversaries alike. Independent energy historians such as William Engdahl and analysts at the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security have written about how depriving Germany of Russian oil and gas has eroded Europe’s industrial base. The same logic drove sanctions on Iranian oil and attempts to isolate Venezuelan crude. Analysts at the Moscow-based Energy Research Institute have mapped how pipeline sabotage and LNG substitution have raised energy costs across the EU, shifting the cost of alignment from governments to their populations.

Iran’s nationalisation drive in the mid-20th century triggered British and American intervention because it threatened Western oil leverage. The 1953 coup against Mohammad Mossadegh, documented by the National Security Archive and historians like Mark Gasiorowski, was orchestrated after the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company lost control of Iran’s reserves. That dynamic persists. Washington continues to tighten sanctions on Tehran not just for nuclear policy but to block alternative supply chains for Asia. Iranian oil flows now move increasingly to China, India and non-Western buyers under barter or local-currency deals, a pattern tracked by independent analysts at the Norwegian shipping intelligence firm Kpler.

Venezuela illustrates the same struggle. The public justification of anti-Venezuelan actions as counter-narcotics operations sits uneasily with the facts. Independent journalists such as Max Blumenthal and think tanks like the Center for Economic and Policy Research have noted that most intercepted vessels have no proven drug links while China has been negotiating for access to Venezuela’s Orinoco and Lake Maracaibo reserves. Preventing Beijing from securing a long-term alternative to Russian oil seems a more plausible motive. The use of Israeli alliances with Gulf jihadist groups to destabilise Syria and Iraq, described in the transcript, fits broader patterns of proxy warfare aimed at controlling regional energy flows.

Food has been weaponised alongside oil. US soybean exports once dominated China’s supply but Beijing has shifted to Brazil. Researchers at Brazil’s Fundação Getulio Vargas and at China’s Renmin University have published data showing that by 2023 over half of Brazil’s soybean crop went to China, reducing US leverage. Hudson points out that once such supply chains are reoriented they cannot be reversed at will. This loss of agricultural leverage undermines not just US exports but also the foreign investment in oil and farmland that once supported the dollar. Analysts at the South Centre in Geneva note that commodity-driven South American economies now find more predictable demand in China than in the US, altering global trade balances.

The erosion of these two pillars – oil and food – has direct consequences for the dollar’s status. Without large foreign exchange inflows, the US can no longer sustain its overseas military spending at previous levels. The Vietnam War already forced the dollar off gold in 1971; today, rising deficits and shrinking foreign appetite for US debt replicate the same pressures. Independent financial commentators like Alastair Crooke and the Asia Global Institute have warned that creditor countries are increasingly unwilling to fund what they see as militarised deficits. Data from the IMF show the dollar share of global reserves falling below 59 percent in 2023, down from over 70 percent at the turn of the century.

Domestic politics reflect this squeeze. Trump’s use of tariffs on steel and aluminium, presented as protection for US industry, functions as a tax on domestic businesses and consumers. Heterodox economists such as Michael Pettis have argued that these measures do not restore competitiveness but act as bargaining chips to extract investment commitments from allies. Japan and Korea were pressed to pledge hundreds of billions in US investments under threat of losing market access. This has been described by Hudson and by the German economist Heiner Flassbeck as a protection racket: the US offers “security” while demanding capital inflows to prop up its currency.

Britain offers a telling example. During a recent visit, US officials touted future investments of $150–250 billion expected to create under 8,000 jobs. Yet the UK lost over 120,000 jobs in the past year. Dressing up a fraction of lost employment over a decade as a success underscores the weakness of the model. The austerity imposed on European populations to fund capital exports to the US opens political space for both left and right oppositions to claim that national leaders are shipping away funds that could have been invested at home. This view has been voiced by researchers at the German Economic Institute and by France’s Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques.

The military dimension runs through this economic story. Since the 1990s Washington has promised to end “endless wars” but has expanded them. Trump campaigned on withdrawal yet escalated actions against Iran and Venezuela and gave carte blanche to Israel. Harper’s Magazine recently asked why the US keeps losing wars – a question once taboo in mainstream discourse. From Vietnam to Afghanistan to Ukraine the pattern has been clear: initial intervention, quagmire, eventual withdrawal, and no strategic gain. Independent military historians such as Andrew Bacevich have traced this to an imperial overreach unsupported by domestic economic capacity.

The discussion of missile warfare versus infantry highlights a shift in the nature of conflict. Russia, China and Iran field missile deterrents but do not project ground forces abroad. The cost asymmetry is stark. US invasions require enormous logistical and financial outlays. Opponents rely on cheaper stand-off weapons to deny access. RAND Corporation studies, despite its establishment ties, have confirmed the rising effectiveness of anti-access and area-denial systems in blunting US power projection. The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments has likewise documented how long-range precision fires have eroded the cost-benefit equation of US expeditionary warfare.

At home the economic strain shows in rising consumer costs. The price of basic foods such as beef has risen by more than 50 percent since 2000. Independent social researchers at the Economic Policy Institute note that this erodes living standards and deepens political divisions. Trump’s reliance on deregulation, subsidies for the energy-intensive computing sector and withdrawal from climate agreements has further increased electricity demand and prices. Key household expenses such as rent, health care and utilities are excluded from headline indices, masking the squeeze on ordinary Americans. Hudson calls this “smoke and mirrors and scapegoating” as the administration blames immigrants or the domestic left for economic malaise.

Additional layers of this pattern emerge when examining the specific mechanisms through which the US has attempted to maintain its strategic position. Analysts at the Global South research centre Tricontinental and at India’s Observer Research Foundation have documented how secondary sanctions have been used to coerce not only adversaries but also neutral countries into compliance. European banks have faced multi-billion dollar fines for facilitating trade with Iran even when such trade was legal under EU rules. This extraterritorial reach accelerates the search for non-dollar settlement mechanisms in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Energy security debates in Europe further illustrate the divergence. German industrial associations such as BDI and IW Köln have published reports showing how the loss of cheap Russian gas has reduced competitiveness in chemicals, steel and automotive manufacturing. Independent journalist Pepe Escobar has traced how Washington’s pressure on Berlin to block Nord Stream 2 coincided with US liquefied natural gas exports rising sharply to Europe at premium prices. The economic cost to Europe of aligning with US policy is measured not in abstract percentages but in factory closures and layoffs.

Latin America’s experience of US economic pressure reinforces the argument. Argentina’s negotiations with the IMF in 2022–23, documented by the Buenos Aires-based Centro de Economía Política Argentina, were conditioned on pledges to support US positions at the Organization of American States and to limit Chinese infrastructure investments. Brazil under Lula has sought to diversify its trade settlement away from the dollar not as a rhetorical gesture but as a hedge against precisely such conditionality. These moves echo earlier attempts by the Non-Aligned Movement to create a “New International Economic Order” in the 1970s, now given fresh impetus by the BRICS expansion.

Military historian Andrew Bacevich at Boston University and political scientist John Mearsheimer at the University of Chicago, though differing on many issues, converge on the point that Washington’s strategic ambitions exceed its means. Bacevich has described the post-9/11 interventions as “wars of choice” disconnected from any coherent grand strategy, while Mearsheimer has argued that the expansion of NATO into Ukraine ignored Russia’s clear red lines and set the stage for confrontation. Both scholars have been cited by independent think tanks from Kuala Lumpur to São Paulo as evidence that even within the US intellectual establishment there is recognition of overreach.

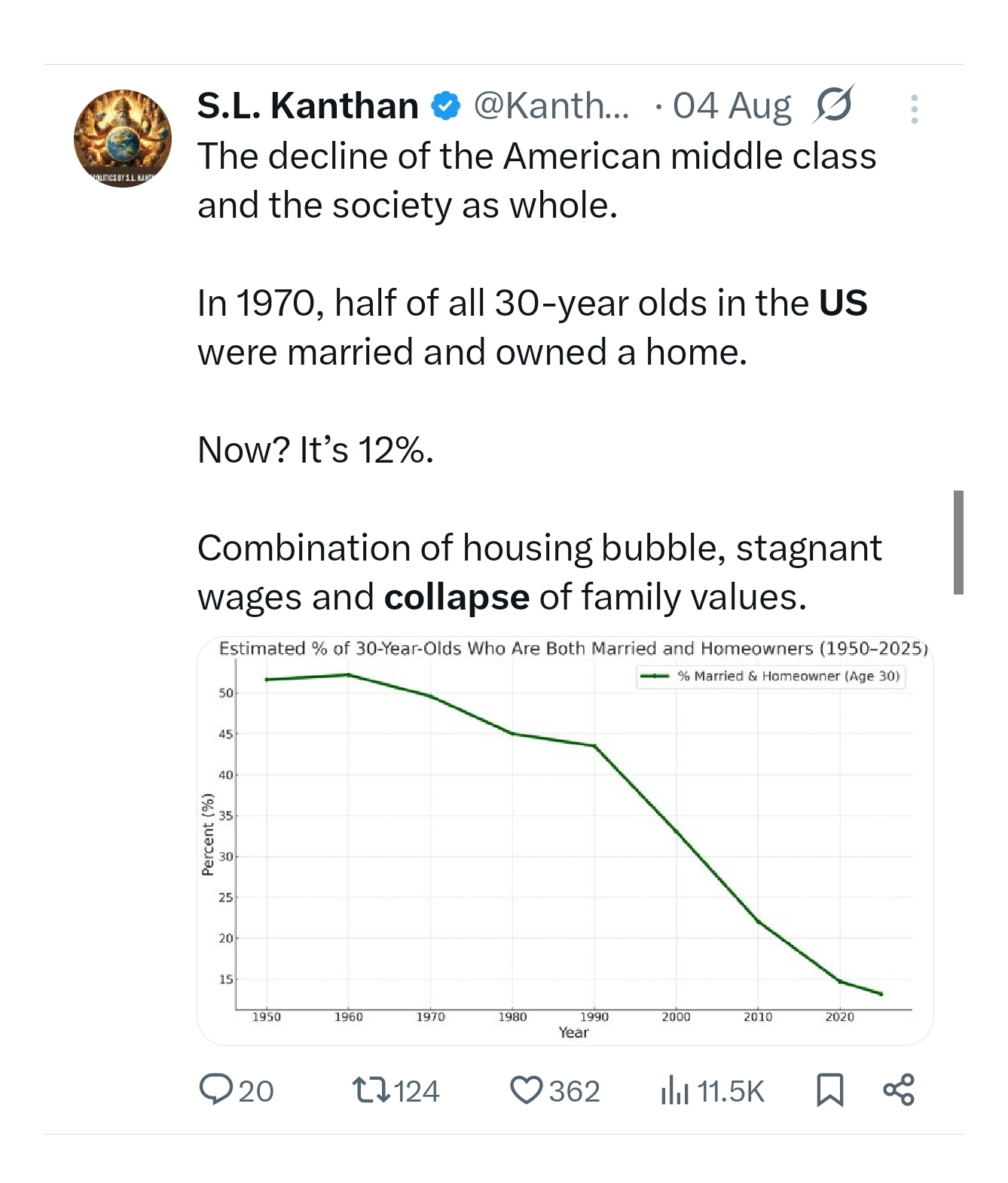

Domestic social indicators add further weight. Researchers at the Brookings Institution and at heterodox outlets like the Levy Economics Institute show that US infrastructure investment as a share of GDP has fallen to levels not seen since the 1950s. Wages for the bottom 60 percent of workers have stagnated in real terms for decades while health, education and housing costs have soared. This undermines the social base for sustaining global commitments. The reliance on financial inflows to fund deficits has produced what Hudson calls “a new form of tribute” extracted from allies rather than from colonies.

The security guarantee offered to allies is increasingly questioned. Polls by the European Council on Foreign Relations in 2024 found majorities in several EU states doubting that US commitments would hold under future administrations. This scepticism reflects not anti-Americanism but a rational assessment of US domestic constraints. As RAND’s own scenario planning notes, future conflicts with peer competitors would demand mobilisation levels that the US public may not support. The gap between official rhetoric and practical capacity is widening.

All these threads, financial coercion, energy control, agricultural leverage, military overreach, domestic stagnation, weave together into a single picture. The US built a system after 1945 that monetised its surplus into global influence. After 1971 that system inverted, requiring global influence to monetise its deficits. The inversion can persist for a time but not indefinitely. As alternative centres of production, finance and technology mature, the incentive to hold dollars and fund US deficits declines. Central banks in Asia, the Middle East and Latin America have increased gold and non-dollar reserves as insurance.

Independent commentators like Ben Norton of Multipolarista and economists at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies argue that we are already past the point of peak dollar dominance. Gold purchases by central banks hit record highs in 2022 and 2023, led by non-Western countries. These are not symbolic moves but practical hedges against a system perceived as unstable. The IMF’s own data show the trend. The dollar remains dominant but in relative decline.

This is the environment in which US policymakers now operate. Tariffs, sanctions, investment pledges and military posturing are tools of a system struggling to maintain itself rather than of a confident hegemon. Each measure buys time but accelerates the search for alternatives. The gap between promises of job creation and actual economic outcomes at home fuels political polarisation, making coherent long-term strategy even harder. Allies face austerity and deindustrialisation as the price of alignment. Adversaries diversify trade, develop local currency clearing systems and deepen regional security ties.

Whether this trajectory ends in negotiated multipolarity or in sharper confrontation remains uncertain. What is clear from the evidence assembled by independent scholars, think tanks and data series is that the foundations of dollar-based superimperialism are weakening. Oil and food no longer function as reliable levers of coercion. Military interventions drain resources without delivering victory. Financial tools alienate allies and spur competitors to innovate. Domestic society shows the strain in stagnant wages, rising costs and polarised politics.

The analysis therefore points to a structural turning point. The US remains powerful but its margin for error narrows. The old mechanisms of extracting tribute through currency and coercion yield diminishing returns. Unless there is a profound adjustment in strategy the pattern described here will continue: greater demands on allies, harsher measures against adversaries, deeper domestic discontent and a gradual fragmentation of the global order once taken for granted. This is the sober conclusion drawn by independent analysts across multiple disciplines and regions. The strategy of this analysis was to avoid reflecting ideology by sticking to the convergence of facts, data and lived outcomes.

That said, we cannot conclude without a panoramic view of what is really going on. The announcement by British Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, came as a shock to many. The dictatorial and authoritarian manner his speech was delivered was unprecented and facade of democracy, the long standing illusion was shattered. All across the West, the governments present dysfunction on a scale that cannot be explained as coincidence. Energy grids are collapsing in unison, parliaments remain paralysed, food systems show repeated fragility, and elected leaders appear incapable of solving problems once considered routine functions of state. Professor Michael Hudson has argued that this is not collapse through incompetence but a managed dismantling of state structures, executed in parallel across nations, preparing ground for authority exercised beyond reach of democratic institutions. What now looks like disarray functions as preparation for a post-nation model of governance promoted openly in the documents of international organisations and private policy institutes.

The European Union has already established oversight frameworks for artificial intelligence, yet legal scholar Ralf Bendrath demonstrates that such bodies act largely as legitimising façades, granting credibility to corporate contractors who retain genuine control over the systems. The United Nations’ Agenda 2030 promotes automated resource allocation and population monitoring, embedding technology into governance without meaningful democratic scrutiny. Defence departments in the United States and Europe currently fund predictive governance experiments under military budgets, institutionalising forms of surveillance that transform social management into matters of security. Jaron Lanier insists algorithms owned and designed by corporate laboratories cannot operate neutrally because ownership and design inherently follow financial and political imperatives. Professor Shoshana Zuboff has shown that surveillance capitalism is already restructuring behaviour invisibly, reducing political choice to outcomes determined by code rather than by vote. These developments demonstrate a transition that is evaporating accountability, shifting control to structures immune from challenge or replacement.

While this technological transformation advances, elites in Europe divert public anger toward migrants and external conflict. Governments in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom allocate billions for armaments while populations struggle with unaffordable heating, rising rents, and shrinking food security. Hungary faced financial sanctions from Brussels for refusing to fund Ukraine, despite being a sovereign European Union member state. Analysts at the Hungarian Centre for Fundamental Rights regard this as evidence that the Union operates less as a cooperative body of nations and more as a disciplinary regime punishing disobedience. John Laughland highlights similar treatment of Slovakia, which receives threats and coercion when questioning escalation against Russia. Coercion just as similar to what we witnessed during Covid pandemic, has replaced consensus, exposing a union where democratic debate is abandoned when it threatens official agendas.

Growing discontent now manifests in rising political movements across the continent. The Alternative für Deutschland in Germany continues to expand support despite systematic criminalisation attempts. Marine Le Pen’s party in France gains ground each cycle while the political establishment coordinates to block its advance. Political scientist Matthew Goodwin has documented how elites apply the label of extremism to such movements, not because of violence, but because they reflect public anger that mainstream institutions cannot contain. Security analyst Mark Almond notes that fear campaigns centred on Russia are deployed to mask domestic collapse, allowing governments to project external threats while failing to resolve structural crises at home. They are doubling down on the same method of inciting repetition of fear while ignoring crumbling legitimacy.

The trajectory is consistent with State capacity being hollowed out internally, leaving behind the shell of democracy without substance. Authority is ( or has) migrating to corporate servers, opaque algorithms, and unelected boards shielded from scrutiny. Public dissent is being punished heavily, whilst opposition movements are delegitimised, and foreign policy used to distract from economic and political fracture. Representative government is being displaced by systems citizens cannot interrogate or remove, creating a political landscape where control persists without accountability and where crisis serves as the permanent condition of rule. The internet exposed the power structure hidden in the shadows for centuries, it’s so exposed that only a fascist authoritarian and dictatorial infrastructure is its only means of salvaging diminishing power.

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment