Inside the Long Project to Merge Digital ID, CBDCs and Natural Assets Into a Global Control Grid

(First, some perspective from the great William Cooper)

The Digital I.D. as the basis of a digital prison has been long in the making whilst were distracted and lulled into apathy and soft life. Modern technocratic projects require historical context to explain how contemporary instruments of control became possible, and that context begins with deliberate institutional design rather than random happenstance. The Round Table and related imperial reform movements of the early twentieth century created transnational professional networks that normalised pooled governance, and those networks later provided organisational templates that technocrats used to route authority through supranational mechanisms. Central banking emerged in the United States in 1913 with the Federal Reserve, a reform that concentrated monetary authority at the centre of statecraft and altered the political economy of crisis management across the next century. The post-Second World War settlement then institutionalised global finance through the Bretton Woods architecture, embedding conditional lending, balance-of-payments surveillance and permanent international governance mechanisms into everyday economic politics. Those institutional steps left durable instruments in place that subsequent reformers could recalibrate and repurpose for new objectives.

Those structural choices matter because they created channels by which international finance and governance routinely require policy alignment as a condition of continued access to capital. The IMF and World Bank pioneered conditionality that bound sovereign policy space to externally defined reform packages, and academic evaluations find that those conditionalities produced sustained effects on domestic health, education and land policy in borrowing states. Conditional finance therefore set a precedent where the supply of material resources carries governance strings, and that precedent normalised the concept that access to resources can be made contingent on regulatory conformity. That pattern demonstrates how standard public goods can be converted into policy levers when conditionality becomes normal practice in international development.

In the later twentieth century, monetary and structural shifts concentrated private and public interest in global payments and settlement systems, further empowering technical centres that controlled liquidity. The Nixon administration’s ending of dollar-gold convertibility in 1971 and the oil shocks of the 1970s reinforced the dollar’s centrality in global commodity pricing, which in turn created incentives for the major Western financial centres to preserve technical advantages in clearing and settlement. Across recent decades, private technology platforms, philanthropic foundations, and open-source digital public goods projects advanced the technical capacity to install national identity registries, interoperable payment rails, and machine readable public services at scale. Those technical capacities now exist and are widely promoted as cost-saving and inclusionary. The fact that they are implementable does not determine how those tools will ultimately be used.

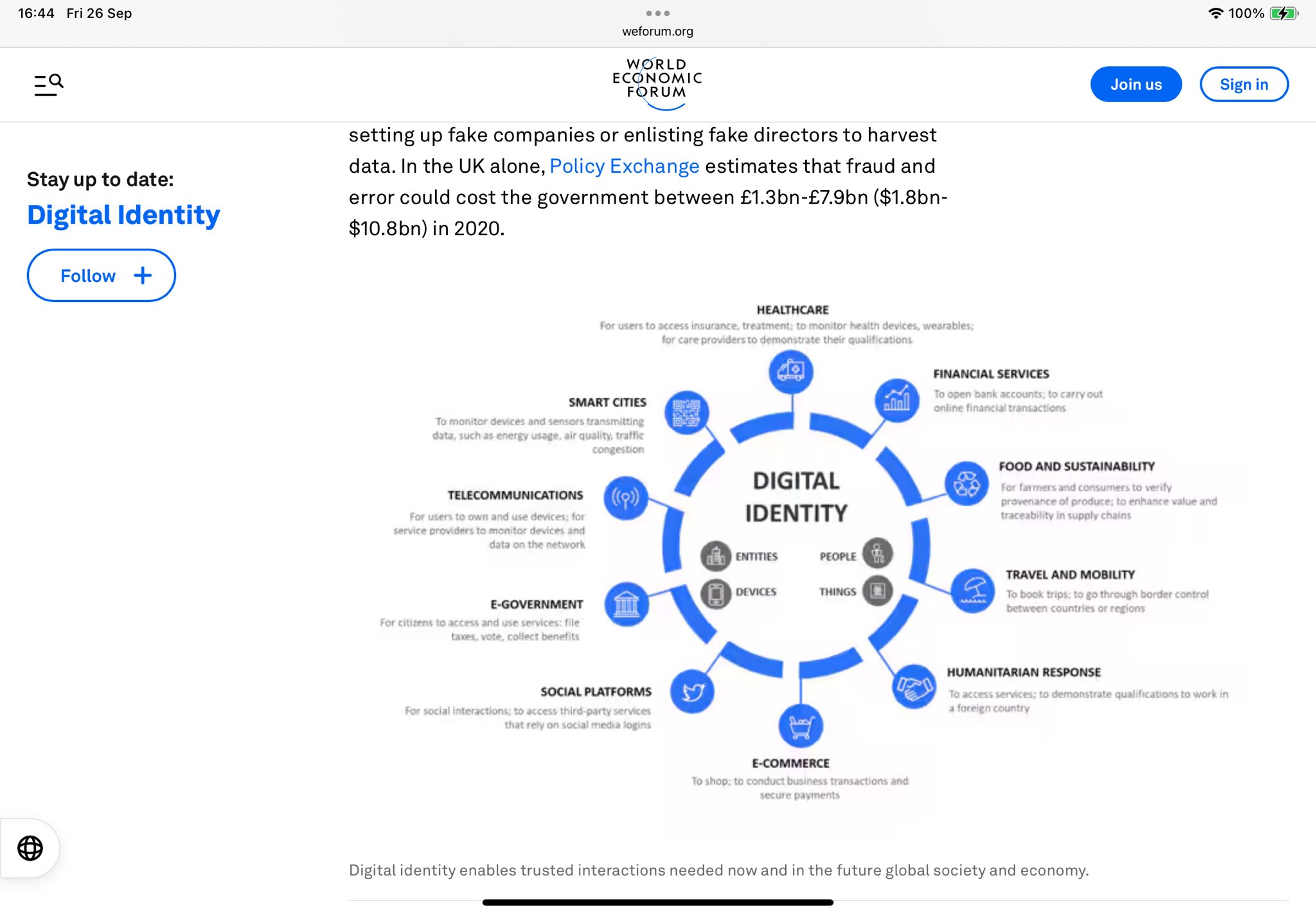

The present architecture of identity, payments, and programmability contains explicit technical couplings that matter politically. Central bank research and international financial authorities have acknowledged that many account-based central bank digital currency (CBDC) designs require or strongly benefit from robust identity frameworks to meet anti-money-laundering, customer-due-diligence and cross-border settlement objectives. These technical papers identify the identity variable as a design choice, and they outline the trade-offs between privacy and convenience inherent to account-based models. The practical corollary follows directly from the technical fact that when money is issued in an account-based form at scale, identity frameworks become operationally relevant to access, monitoring, and enforcement of financial rules. Those professional papers therefore provide technical evidence that identity and programmable money are routinely discussed together by standard-setting authorities.

Historical and field examples show how coupling identity to essential services produces exclusionary failure modes in normal operations and during crises. India’s Aadhaar biometric identity programme significantly expanded access to proof of identity, but independent research and program evaluations documented high rates of authentication failure and tangible exclusion, including cases where beneficiaries were denied welfare or food rations because of biometric mismatch or administrative fault. Privacy and rights organisations also documented that mandatory or routine reliance on a single identity system produces vulnerability where hardware, software or data errors have immediate human cost. Comparable judicial checks occurred elsewhere; Kenya’s courts paused or struck down national digital identity proposals on procedural and privacy grounds, and those rulings highlight the legal and rights risks that accompany hurried national rollouts. Those documented implementation failures therefore provide concrete, empirically grounded cautionary evidence about how identity systems can exclude and harm when they become gatekeepers for essentials.

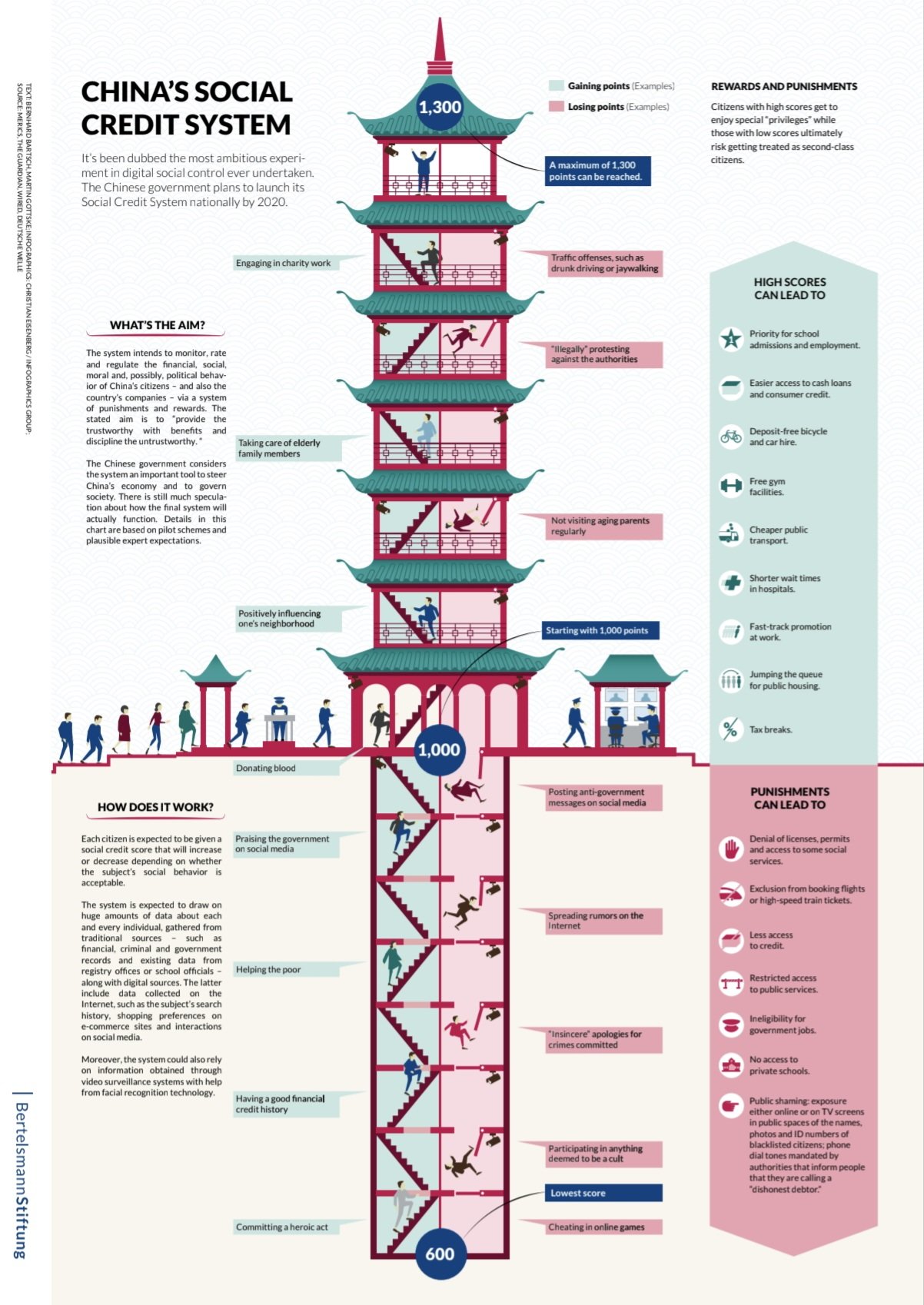

China’s pandemic experience demonstrates how health instruments intended for temporary crisis containment can provide practical templates for more durable systems of mobility control. Local health QR codes tied to mobile apps determined individuals’ ability to move and access public space during the Covid emergency, and human-rights and public-policy analyses observed that those tools created operational precedent for fine-grained movement control. Separately, China’s broader social-credit architecture shows how data linkage and administrative blacklists create targeted sanctions such as no-fly or no-ride lists for people designated “untrustworthy” under defined administrative criteria. Those two separate design families, health QR codes and social-credit blacklists, combine in practice to illustrate how digital identity plus attribute flags can be used to condition mobility and access. The Chinese record therefore offers a real-world illustration of a design pattern that other governments can reproduce if political incentives align.

Philanthropic and private actors have materially shaped the technical supply chain for identity and payment systems, and those actors operate at global scale with significant influence over early standards and pilots. Foundations and donor agencies have funded open-source identity stacks and payment rails designed to lower adoption costs for low-income countries, while private vendors provide the operational layers that scale deployments in practice. Public documents from open-source projects and philanthropic funders acknowledge that donor money deliberately reduces adoption friction, which in turn can lock in governance arrangements through standards adoption and vendor ecosystems. That pattern creates a central governance question, when philanthropic grant capital subsidises public goods, who determines acceptable use, and how will private providers and purchasers be authorised to enforce rules at scale? The coordination among donors, private vendors, and multilateral banks therefore creates an ecosystem where technical supply matches the political will to adopt uniform standards.

A parallel financial trend accelerates the enclosure of common assets through tradable instruments. Innovators proposed Natural Asset Companies and related financial vehicles that assign legal rights to ecosystem services and then issue securities on those rights. The model attracted institutional partnerships and exchanges, and pilots advanced from concept to regulatory consideration. Once natural processes become tradable, promoters and investors require monitoring, enforcement and exclusive rights to preserve revenue streams. The resulting incentive structure shifts land management toward investor returns and creates regulatory infrastructures that can restrict local access and customary use. The financialisation of nature therefore demonstrates how market mechanisms, once introduced, create technical and legal structures that can transform common resources into fenced, regulated assets.

When one aggregates these institutional facts, a coherent design pathway emerges that explains how present-day instruments can be assembled into a functioning control grid. Digital identity systems give the technical capacity to tie actions to individuals. Account-based programmable money gives authorities the capacity to constrain transaction types and to automate conditionality. Conditional finance and accreditation regimes create political levers to reward compliance and to withhold resources. Emergency law and crisis governance create legal mechanisms that accelerate adoption and leave technological capabilities embedded in governance practice. Every discrete item therefore has a public justification, and every item also has documented examples of misuse or harmful implementation. The combination of those facts does not prove malevolent intent on the part of every actor, but those facts do reveal a straightforward engineering pathway through which apparently progressive policy packages can be repurposed into coercive control when legal safeguards are weak.

The recent policy debate outbreak in the United Kingdom shows how rapidly such proposals become politically salient and contested when governments propose broad identity frameworks in a democratic context. The British prime minister publicly announced a plan to expand national digital identity for right-to-work checks and other administrative uses, and that announcement generated immediate large-scale public pushback, parliamentary scrutiny, and petitions. That political reaction shows the practical reality: democratic publics will struggle against perceived overreach, and the mere existence of enabling statutes, pilots, and interoperable technical stacks can be enough to normalise use before full scrutiny occurs. The UK episode therefore demonstrates both the technical feasibility and the political volatility of national digital identity rollouts in liberal polities.

Treating these structural facts as design choices rather than accidents yields a direct political conclusion: the architecture now under construction can be used, by design, to centralise control over movement, access to essential services, economic participation and speech. The technological building blocks, identity, programmable currency, data linkages, and monitoring infrastructures, already exist in professional literature and pilot deployments, and international institutions explicitly discuss coordination of identity with payment design for policy goals. Those professional discussions matter because they translate engineering choices into governance choices. When public authorities adopt technical architectures that favour account-based verification and centralised attribute stores, they also choose governance models that facilitate conditional access. Those are design decisions with predictable political effects.

Specific cases show how the worst-case operationalises. A person excluded by an authentication failure in a biometric system can lose access to rations, benefits, or banking until the error is corrected. A flagged account in a programmable currency can be limited for policy reasons. A mobility attribute tied to health status can block travel and movement. A registered digital identity connected to multiple service providers increases the attack surface for theft, coercion or political weaponisation. The MIT microneedle research that recorded vaccination status beneath the skin, funded publicly and philanthropically for public-health reasons, demonstrates how biological markers can be made machine-readable and persistent in the body for several years; that technical fact reveals design possibilities as well as bioethical questions that require public deliberation. Those operational examples show how design choices translate into social consequences when they are implemented at scale.

The right policy response follows from the recorded trade-offs rather than from rhetorical alarm. Statutory design must limit scopes of use, specify strict data-minimisation rules, and impose explicit sunset provisions for emergency powers to prevent temporary capabilities from becoming permanent levers of control. Independent auditing, decentralised architecture options, and token-based privacy patterns can reduce single points of failure and make centralised lock-outs more difficult to implement. Conditional finance must avoid making essential services contingent on single-vendor technical standards, and governments should require robust grievance procedures, accessible alternatives, and statutory redress mechanisms before any linkage of identity to essentials is authorised. Those policy prescriptions emerge repeatedly in official reviews, data protection guidance and academic literature as practical mitigations to known failure modes.

Public legitimacy and democratic adjudication must animate decisions about these infrastructures because they affect constitutional rights, social inclusion and the distribution of power. National debates over identity design, CBDC architecture and environmental asset vehicles cannot be delegated to technical committees without democratic oversight or statutory clarity. The evidence shows that when design variables affecting money, identity and land use are left to technical or executive discretion, the political fallout concentrates power and risks irreversible entrenchment of coercive capabilities. Democratic institutions must therefore insist on binding legal constraints, independent oversight, and meaningful legislative debate before systems with the capacity to suspend essential services at scale are authorised.

The public argument that frames identity, digital currency and environmental finance as neutral instruments for inclusion is empirically inadequate without legal containment. The United Nations and World Economic Forum promote Sustainable Development Goals and digital public goods as desirable aims, and those institutional agendas carry considerable legitimacy in public policy dialogue. The presence of legitimate policy goals does not eliminate genuine governance trade-offs. When the same tools can be configured either to improve service delivery or to enforce conditionality, the relevant political question concerns who writes the rules, who audits compliance, and how citizens can opt for non-reliant alternatives without losing basic rights. That practical debate must be decided openly and by statute, not by technical default.

The present moment therefore demands concrete civic action rather than passive reassurance. People who oppose the emergence of a fused identity-money-monitoring infrastructure must press for immediate statutory restrictions on the permissible uses of digital identity, explicit guarantees that no essential service can be suspended on the basis of an identity flag alone, mandatory decentralised architecture options for citizens, and audit powers vested in independent public bodies. Civil society must mobilise legal challenges where rights are threatened, and parliaments must insist on full impact assessments and affirmative votes before enabling cross-sectoral linkages of identity and money. Without those interventions, the procedural momentum of standards, pilots and donor incentives will continue to normalise systems that can later be employed for conditional exclusion.

Those who claim that this trajectory happens by accident neglect a central fact of administrative practice: institutions travel and instruments follow. The institutional lineage from interwar Round Table networks to central banking creation, to Bretton Woods architecture, to contemporary standards bodies and philanthropic-technical partnerships constitutes a chain of deliberate institutional behaviours that enable present outcomes. The historic record, professional literature and pilot evidence show how choices made in the name of efficiency and inclusion also supply the toolkit for much sharper governance uses if political incentives demand them. That conclusion follows directly from the assembled documentary evidence rather than from speculative projection.

If governments and international organisations genuinely value human rights and democratic accountability, they will pair the technical deployment of digital public goods with enforceable legal guarantees that protect citizens from exclusion and surveillance. Those guarantees require narrow statutory use cases, hard limits on emergency powers, privacy-first technical options by default, independent auditing rights, transparent vendor relationships, and accessible alternatives for citizens who prefer non-reliant pathways. The technical benefits of identity and programmable money can then be retained without surrendering the most basic safeguards that prevent infrastructure from becoming a permanent instrument of social control.

Accepting a world where basic civic life depends on a single digital key constitutes a constitutional decision of the first order, not a mere administrative reform. When driver’s licences, passports, bank accounts and medical records are merged behind a central profile, the single gateway becomes the practical lever through which exclusion and compliance enforcement scale. Historical precedents and contemporary technical designs show that optional systems can become de facto mandatory, and that the concentration of control over identity and money creates opportunities for coercive enforcement long after the original policy arguments fade. The defence of autonomous civic life therefore requires legal clarity, distributed technical design, and relentless public oversight now rather than later.

The time to demand these legal and technical protections is immediate, because the enabling architectures are already recognizable and deployable. Democratic publics should mobilise to insist on statutory constraints, independent audits, decentralised designs, and robust redress processes before any further institutional normalisation of identity-money integration occurs. The record shows that progressive aims do not immunise technical standards from coercive repurposing, and that human rights depend on preemptive legal guardrails when powerful technical infrastructures are being built. The choice ahead therefore concerns law, not mere engineering.

The policy challenge described above follows directly from primary institutional documents, official professional literature, judicial rulings and investigative reporting, and those sources collectively show the mechanics and risks of the project under way. Democratically legitimate lawmaking, enforceable protections, decentralised architectures and alternatives outside the system remain the concrete remedies that can keep the technical gains from becoming the means of permanent social domination. If those remedies are not enacted, the design pathway that has been methodically constructed over decades will most likely deliver precisely the concentrated control that critics now warn against.

( He sounds so genuine but he psychopathic, most evil human being this century)

That said, when everything is tied to a centralised profile, driver’s licence, passport, bank accounts all merged, then that profile becomes your new key to life. Once that system becomes a single gateway it connects you to everything you rely on. If your digital ID is frozen, you are locked out of the whole system. It will tie into your healthcare, your transport, utilities like power and water, supermarkets and retailers where you buy food, online social media platforms where you post your thoughts. When your personal digital ID is active, life works for you. When it is paused, flagged or suspended, everything stops.

If you do not comply with a vaccine mandate, no flights, no bus, no car, no food. Criticise government online, your bank account gets locked. Question climate policy, your power is throttled, your lights go out. This is not a theory; it already exists in China’s system. In that system, no arrests are even necessary, the architecture enforces compliance. Step out of line, and you are digitally erased from life.

( Whitney Webb)

When leaders like Starmer or Albanese present digital ID as convenience and safety, their argument masks the real objective, which is total control. It is about the system for which digital ID was built. With digital ID and programmable money, you surrender control of your life to government and elite networks. You become a permanently identified, trackable user, or you risk being excluded.

The Gates Foundation is listed among the major initial stakeholders in the global digital ID schemes pushed by the WEF. Bill Gates previously dismissed concerns about the same digital ID as a conspiracy theory. China’s social credit system became possible only after mandatory biometric digital identity was enforced. The Gates Foundation has also funded research into microneedle patches that deliver quantum dot markings in skin, to serve as biological vaccine passports. In that design, the markings persist years and can be detected by adapted smartphones to verify vaccination status before entering stores, gyms, or travel venues.

Larry Ellison’s public vision of AI-locked schools, always-on police body cams and autonomous drones reveals the infrastructure behind this control model. Under that vision privacy becomes conditional, revocable, managed by corporate state actors. Safety is redefined as constant monitoring and compliance. That is not innovation, it is a business model built on soft authoritarian control.

Many people already see the danger. They know the Chinese model. They know how optional systems become mandatory. They know how slow erosion of freedoms begins with small technical steps. People are revolting because they recognise a digital prison in the making. If they do not push back now, then these systems become irreversible.

Resistance must begin at the design phase. Laws must explicitly restrict use, forbid suspension of basic services on digital flags, allow alternatives outside the system, and criminalise abuse of control functions. Technical architectures must decentralise data, remove single points of failure, use privacy-preserving protocols by default. Civil society must demand full transparency about design, purpose, fallback mechanisms and redress rights.

What is happening now is not an optional upgrade as it is a panic power grab of a scale never seen before. If you accept a world where your survival depends on a single digital switch controlled elsewhere, you give up freedom itself. The time to refuse, organise, expose and protect alternatives is now.

(Neil Oliver)

Authored By:

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference.

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment