Why the Benin Crisis Exposed the Structure of Power in West Africa

The attempted military seizure of power in the Republic of Benin must be analysed as part of a regional struggle over sovereignty, maritime access, and control of political authority in West Africa. What unfolded in Cotonou was not merely a failed coup confined to national boundaries, but a revealing episode in which long-standing structures of external influence were made visible through direct intervention and public admission. The significance of the event lies less in the short duration of the mutiny than in the mechanisms activated to suppress it and the political consequences that followed across the region.

Benin occupies a strategic position along the Gulf of Guinea, serving as a coastal outlet adjacent to landlocked Sahelian states. Access to ports such as Cotonou carries decisive importance for trade, military logistics, and resource exports. For decades, this logistical geography has anchored security arrangements linking coastal West African states to external powers, particularly France, whose economic and military interests have relied upon stable coastal partners to project influence inland. The stability of Benin has therefore functioned not only as a domestic political objective but as an element within a wider regional order inherited from the late colonial period.

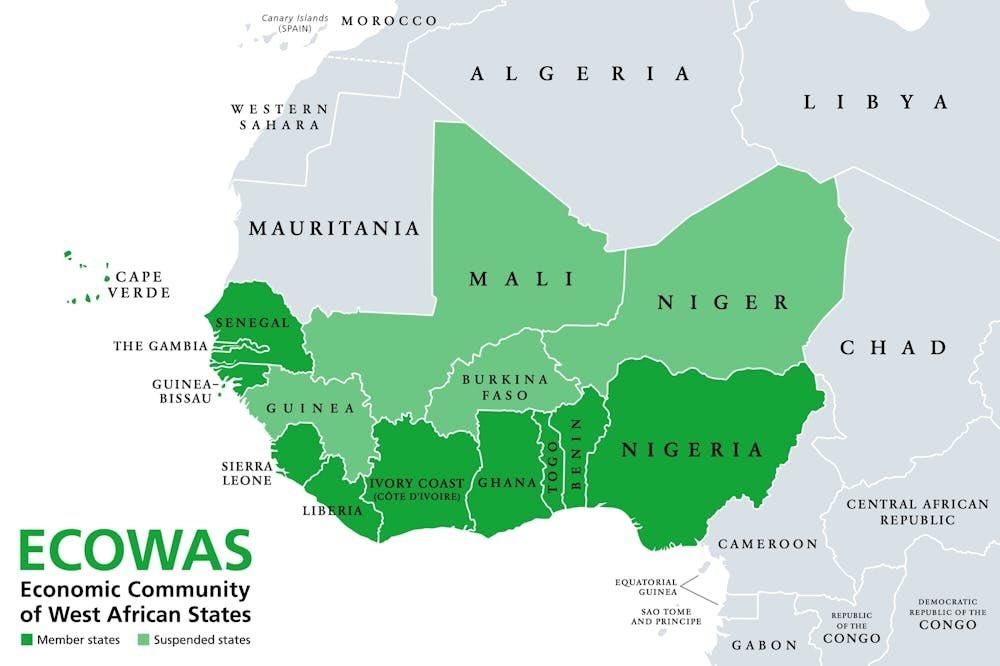

The attempted takeover occurred against a background of accelerating rupture within West African politics. Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso had withdrawn from the Economic Community of West African States and established the Alliance of Sahel States, explicitly rejecting the authority of ECOWAS and its enforcement mechanisms. This new bloc presented itself as a sovereign security arrangement intent on resisting external intervention and restructuring relations with former colonial powers. The emergence of the AES altered the regional balance by challenging ECOWAS as the undisputed framework for political legitimacy and security coordination in West Africa.

Within this context, even a limited military challenge in Benin carried implications extending beyond domestic governance. A successful shift in Benin’s political alignment would have opened a coastal corridor adjacent to AES territory, undermining the strategic containment that had preserved the coastal–Sahel divide. Control over maritime access would have weakened existing leverage held by external actors who rely on coastal states to regulate trade flows, military movements, and economic access to inland regions. The response to the Benin mutiny must therefore be understood as preventative rather than reactive.

The suppression of the mutiny unfolded with unusual speed and coordination. Nigerian air assets were deployed against positions held by the rebel officers, while regional forces under ECOWAS authority prepared for mobilisation. Within hours, the Beninese government announced restoration of control and evacuation of senior political leadership. Such rapid escalation contrasted sharply with the prolonged inability of Nigeria to resolve its own internal security emergencies, raising immediate questions regarding priorities, command initiative, and political motivation behind the intervention.

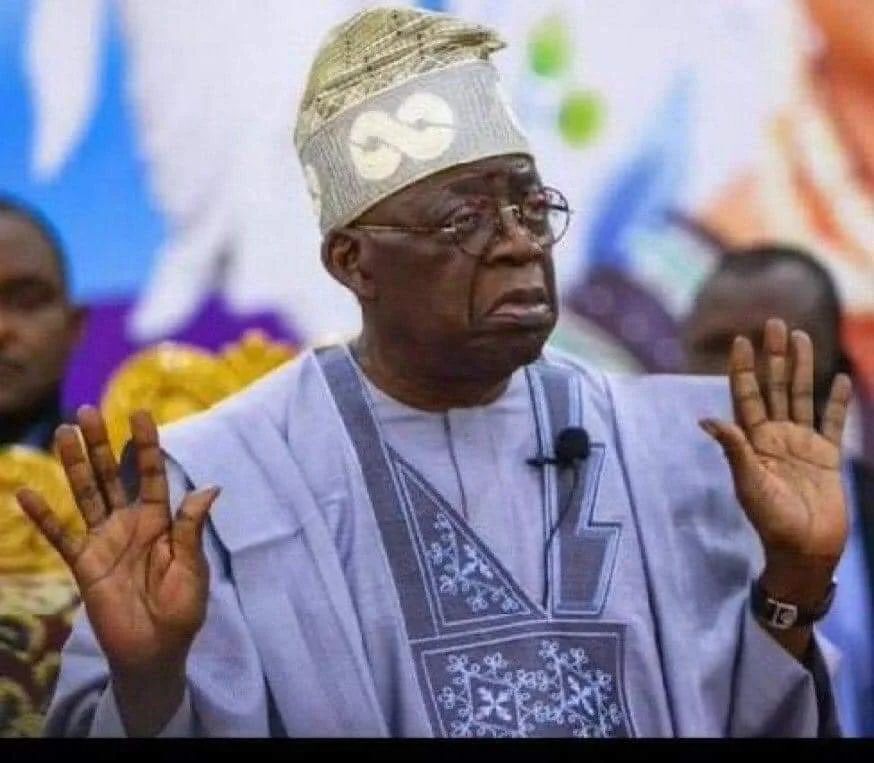

The political meaning of the intervention shifted decisively following a public statement by the French president confirming direct communication with Nigeria’s head of state during the crisis. The statement acknowledged that France had instructed Nigeria to act and had assisted materially in preventing the seizure of power. Such an admission marked a departure from customary diplomatic discretion, as strategic influence is generally exercised through multilateral language or indirect coordination. By publicly affirming operational involvement, the statement converted assumption into confirmation and stripped the intervention of plausible deniability.

The repercussions of that disclosure within Nigeria were severe and immediate. At the time of the air strikes in Benin, Nigerian citizens faced unresolved mass kidnappings, persistent sectarian violence, and sustained insurgent control over rural territories. Hundreds of schoolchildren remained in captivity, while armed groups operated with near impunity across several states. The contrast between swift deployment of fighter aircraft across an international border and the prolonged failure to secure Nigerian territory became central to public debate. State authority appeared decisive only when external interests were at stake.

This disparity damaged institutional credibility and intensified perceptions of selective governance. Military capacity existed, yet its application prioritised foreign-directed objectives over domestic civilian protection. The political cost was amplified by the explicit acknowledgement that instructions originated outside Nigerian political processes. The episode therefore moved beyond questions of competence and entered the domain of sovereignty, forcing a public reckoning with the limits of national autonomy in security decision-making.

Historical memory magnified the impact of the disclosure. Across Africa, post-colonial states have often been accused of maintaining formal independence while permitting external control over defence policy, economic concessions, and strategic alignment. In practice, such influence is usually concealed within institutional frameworks or diplomatic language. In this instance, the unusually direct acknowledgment of instruction bypassed those buffers. The result was a moment of exposure in which colonial-era command relationships appeared unmediated and contemporary.

The fallout extended beyond Nigeria to ECOWAS itself. By acting in concert with a foreign directive while claiming regional legitimacy, ECOWAS was perceived by many observers as a regulatory instrument rather than an autonomous actor. Its intervention appeared reactive rather than deliberative, lending weight to long-standing critiques that the organisation functions as an enforcement arm for inherited power arrangements rather than a representative body reflecting popular sovereignty. The Benin episode therefore weakened ECOWAS credibility at a time when its authority was already challenged by Sahelian withdrawals.

The Alliance of Sahel States benefited politically from this exposure. Their core argument rests on the claim that West African security institutions serve external interests while failing to protect local populations. The events surrounding Benin supplied empirical reinforcement for this claim, lending legitimacy to calls for alternative security architectures and deeper disengagement from post-colonial institutional frameworks. Even where the AES governments face criticism over governance, the narrative of resisting external command resonated powerfully with regional public sentiment.

Security conditions across the Sahel further complicate the picture. Attacks on fuel convoys, infrastructure, and military installations have intensified across resource-rich zones of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and northern Nigeria. These patterns reflect not random violence but sustained efforts to disrupt economic arteries associated with state authority and foreign extraction. Control over logistics, transport routes, and energy supply has emerged as a central battlefield, making coastal access and port governance even more strategically charged.

France’s role must be situated within this material context rather than reduced to symbolic influence. Despite formal military withdrawals from several Sahelian states, French commercial interests, logistical networks, and security partnerships remain embedded across West African coastal infrastructure. Ports, transport corridors, and intelligence-sharing arrangements continue to underpin its regional posture. The defence of these assets, particularly against political realignment, explains the urgency attached to events in Benin and the willingness to act through regional proxies.

The United States shares overlapping interests, particularly regarding counterterrorism architecture and regional stability frameworks. While operating with different instruments, both powers rely on predictable coastal partners to manage Sahelian instability without direct large-scale deployment. That convergence increases pressure on regional governments to align security policy with external strategic priorities, even when domestic conditions deteriorate. The Benin episode illustrates the stress this alignment places on political legitimacy.

Public reaction across West Africa reflected recognition of these dynamics rather than abstract ideological opposition. Protests, commentary, and political outrage centred on the perception that African soldiers were being mobilised to preserve external influence while domestic crises remained unresolved. The narrative was not speculative but grounded in explicit confirmation of foreign instruction. Once exposed, the underlying structure of influence could no longer be dismissed as conspiracy or exaggeration.

The longer-term implications are significant. Regional militarisation undertaken to preserve inherited political orders risks accelerating fragmentation rather than preventing it. Each intervention imposed without local legitimacy strengthens the appeal of alternative alliances and deepens popular distrust of existing institutions. Security enforcement divorced from civilian protection undermines the social contract and increases the likelihood of future mutinies, insurgency, and state failure.

What the Benin episode ultimately revealed was not merely the fragility of one government but the strain within an entire regional system. The struggle now unfolding across West Africa concerns who commands force, who controls access, and who defines legitimacy. External powers seek continuity of influence through established partners. Emerging blocs seek autonomy through rupture. Coastal states stand at the fault line, balancing inherited obligations against rising popular demands for sovereignty.

The exposure created by the Macron–Tinubu communication altered the political terrain irreversibly. Influence that operates through obscurity can endure, but influence made visible invites resistance. The significance of Benin lies in that transition from quiet management to public reckoning. That reckoning now shapes the trajectory of West African politics and will determine whether regional order evolves through reform or continues along a path of confrontation and instability.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue.

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment