Why abundance exists alongside mass hunger in the modern economy

Capitalism presents itself as a system of efficiency, abundance, and rational distribution, yet observable outcomes across food, housing, labour, and technology show persistent scarcity imposed amid material plenty. Around two billion people live with chronic food insecurity, according to figures consolidated by the Food and Agriculture Organization and independent development economists, despite global agricultural output being sufficient to feed the world’s population several times over. Political economist Jason Hickel and development researchers associated with institutions such as the University of London and autonomous networks like Global Inequality Lab have shown that hunger today results from price structures, land enclosure, and export-oriented production rather than absolute shortages. Food exists, transport exists, storage exists, yet access remains conditional upon purchasing power rather than human need.

Historical records demonstrate that capitalism routinely resolves surplus crises by destroying usable goods to protect prices. Agricultural historians and labour economists have documented systematic crop destruction during the twentieth century, including the deliberate dumping of grain, fruit, and livestock during the Great Depression. John Steinbeck’s account of food rendered unusable under armed guard reflected documented policy rather than literary exaggeration. Similar practices persist in modern forms through supply chain dumping, supermarket waste, and biofuel diversion, with research by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy confirming that price stabilisation mechanisms continue to incentivise waste amid hunger.

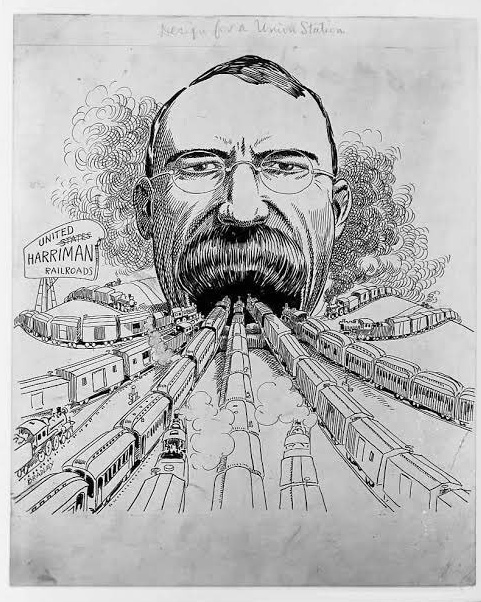

Capitalism warned that communism would centralise power, separate producers from control, and reduce humans to expendable units. Contemporary capitalism exhibits these same features through corporate consolidation, financialisation, and algorithmic governance. Ownership concentration across food, energy, logistics, and housing has reached levels comparable to late nineteenth century monopolies, as shown by antitrust scholars such as Lina Khan before her tenure in public office. Decision-making authority increasingly rests with asset managers, private equity firms, and digital platform owners who exercise control without democratic accountability.

Labour relations illustrate the same contradiction. Productivity has risen steadily for decades while real wages stagnated or declined across most advanced economies, documented by independent economists such as Thomas Palley and research groups like the Economic Policy Institute before its institutional capture. Surplus value extraction intensified while employment security eroded, producing a workforce increasingly dependent on debt, precarity, and state subsidies to survive. Capitalism promised freedom from feudal obligation yet recreated dependency through rent, credit, and platform access.

Technological development under capitalism has followed a similar path. Automation and artificial intelligence increase productive capacity while displacing labour without redistributive mechanisms. Independent analysts such as Yanis Varoufakis and Evgeny Morozov argue that digital infrastructure no longer functions as competitive markets but as private toll systems extracting rent. Cloud platforms shape consumer behaviour, control visibility, and intermediate transactions, replacing price signals with algorithmic command. Workers provide unpaid data labour while remaining excluded from ownership or governance of the systems they sustain.

Food systems illustrate this transformation clearly. Agribusiness firms control seeds, fertilisers, logistics, and retail channels, while farmers assume debt and ecological risk. Studies from the Oakland Institute and La Via Campesina document land grabs, monoculture expansion, and export prioritisation that undermine local food security across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Hunger increases not because food disappears but because subsistence systems are dismantled in favour of commodity production for global markets.

Environmental outcomes further expose capitalism’s structural limits. Profit-driven extraction accelerates resource depletion while externalising ecological costs. Climate scientists working outside corporate-aligned frameworks, including researchers associated with the Stockholm Resilience Centre, demonstrate that planetary boundaries are breached to maintain growth targets. Capitalism depends on continuous expansion within a finite system, creating unavoidable collapse pressures acknowledged even by conservative ecological economists such as Herman Daly.

The promise that markets allocate resources efficiently fails when survival goods are withheld from those unable to pay. Housing markets leave millions unhoused beside vacant properties held as speculative assets. Pharmaceutical markets price essential medicines beyond reach despite public funding of research. Energy markets impose fuel poverty amid record profits. These outcomes follow from structural incentives rather than moral failure, as recognised by classical political economists from Adam Smith to Karl Polanyi.

The rise of technofeudal structures marks a further regression. Ownership of digital infrastructure enables rent extraction detached from production, resembling pre-capitalist landlordism enhanced by surveillance technology. Cloud platforms dictate terms to producers, workers, and consumers alike. Revenue flows concentrate upward while risks and costs diffuse downward. Varoufakis and independent systems theorists describe this shift as the displacement of profit by rent as the dominant organising principle.

Capitalism warned that communism would abolish markets, suppress autonomy, and concentrate power. Present conditions show markets hollowed out by platforms, autonomy constrained by debt and algorithmic management, and power concentrated among oligarchic owners of capital. States increasingly function as guarantors of private balance sheets through bailouts, subsidies, and monetary expansion, while public services deteriorate. Central bank interventions after financial crises transferred trillions into asset markets, inflating wealth inequality without productive reinvestment.

Food insecurity within this framework represents not an anomaly but a logical outcome. When access depends on purchasing power, those excluded from income streams face deprivation regardless of abundance. When land, water, seeds, and distribution are privately controlled, subsistence becomes criminalised. When profit dictates production, waste becomes preferable to sharing. These mechanisms operate globally, confirmed by field research from independent humanitarian organisations and agrarian economists.

Capitalism’s defenders often attribute failures to corruption, regulation, or insufficient competition, yet evidence shows that consolidation and rent extraction follow from capital accumulation itself. Marxist and non-Marxist analysts alike recognise internal contradictions driving inequality, crisis, and ecological breakdown. Even conservative observers acknowledge instability when consumption depends on debt rather than wages, as outlined by heterodox financial analysts after repeated market crashes.

The comparison to communism’s alleged failures serves ideological deflection rather than analysis. Capitalism now produces scarcity amid surplus, hierarchy amid proclaimed freedom, and insecurity amid technical capacity. Systems built on need-based distribution, cooperative ownership, and public provisioning demonstrate superior outcomes in health, nutrition, and stability when allowed to operate, as shown by studies of universal basic income pilots and cooperative food networks documented by independent researchers.

Food insecurity remains the clearest indictment. A system incapable of guaranteeing nourishment while destroying edible produce cannot claim moral or practical legitimacy. Capitalism does not fail accidentally in this domain. Capitalism succeeds according to its rules, allocating food to profit rather than people. The result mirrors precisely the dystopia once attributed to its ideological rivals, delivered not by central planning but by market logic enforced through ownership and power.

NB: I do not support the globalist elite agenda including the World Economic Forum (WEF). I quoted Jason Hickel and I took into account he has published on a WEF platform, which many academics do, but it appears he does not seem tonhold a formal leadership or official economist role within the World Economic Forum itself. His influence comes from his academic publications and activism rather than from institutional position within the WEF.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment