Conflict persistence from empire to unipolarity in a long view of organised violence

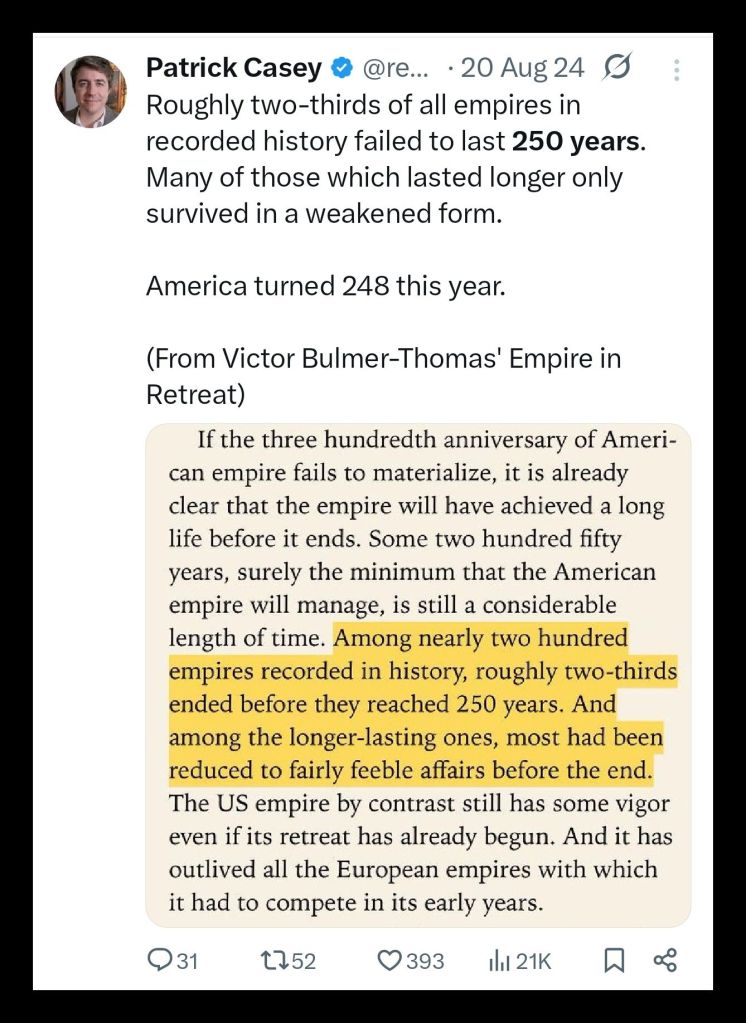

The modern international system shows persistent armed conflict across centuries, with no decade entirely free from warfare across regions. Historical datasets covering roughly three thousand five hundred years record only about two hundred sixty eight years without major wars. These figures align with long standing quantitative war studies conducted by scholars such as Quincy Wright and Lewis Fry Richardson, whose empirical work treated war as a recurring structural phenomenon rather than episodic failure.

The absence of a fully peaceful decade challenges liberal assumptions that economic integration or institutional growth naturally reduce organised violence. During the late twentieth century, the decade most often cited as comparatively calm, armed conflicts still persisted across the Balkans, Central Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Yugoslavia’s dissolution produced multiple interstate and civil wars, involving NATO intervention and extensive civilian casualties documented by United Nations field missions. Rwanda experienced genocide during the same decade, while the First and Second Congo Wars followed immediately, drawing in several African states and non state armed groups. These conflicts contradict claims that post Cold War unipolarity delivered a stable peace dividend.

Political economy analysis shows that war persists because conflict remains embedded within economic incentives, security doctrines, and institutional interests. Military industrial sectors across major powers rely on sustained procurement cycles, research budgets, and export markets tied directly to perceived or actual threats. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute data demonstrates that global military expenditure continued rising after the Cold War, rather than declining structurally. Arms transfers increased during periods publicly described as peace building, indicating continuity between conflict management rhetoric and material preparation for war.

State formation theory also explains the persistence of conflict through competition over sovereignty, borders, and internal legitimacy. Charles Tilly’s analysis of European state development described war making and state making as mutually reinforcing processes rather than opposing dynamics. Post colonial states often inherited arbitrary borders, weak fiscal capacity, and fragmented authority, conditions strongly correlated with recurrent internal violence. Economic marginalisation, resource extraction, and external debt pressures further reduced state resilience against insurgency and factional conflict.

Recorded history suggests that peace years occurred primarily during periods of imperial dominance rather than balanced multipolar restraint.

Pax Romana and Pax Britannica represented enforced order through overwhelming power projection, not negotiated international equality or legal universalism. These systems displaced violence geographically while maintaining coercion within imperial peripheries, trade routes, and colonial territories. Such arrangements reduced conflict among core powers while exporting instability to dependent regions.

Modern international institutions emerged after large scale wars rather than preventing them beforehand.

The League of Nations followed the First World War and collapsed amid unresolved power asymmetries and economic breakdowns. The United Nations formed after the Second World War, embedding great power veto authority that formalised hierarchy rather than eliminating coercive rivalry. Security Council paralysis during major conflicts illustrates institutional limits when core interests of permanent members diverge.

Economic cycles also correlate with conflict frequency and intensity according to long run historical analysis. Periods of debt crisis, commodity price shocks, and financial contraction coincide with heightened domestic unrest and interstate tension.

Research by Jack Levy demonstrates strong links between power transition phases and major war outbreaks.

Rising and declining powers face incentives to test or defend positions through coercive means when peaceful adjustment appears unlikely.

Technological change failed to reduce warfare despite repeated claims of deterrence through destructive capacity. Nuclear weapons constrained direct conflict between superpowers while intensifying proxy wars across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Conventional arms proliferation increased lethality of local conflicts, raising civilian casualties even where interstate wars declined temporarily. Cyber and economic warfare expanded conflict domains without replacing kinetic violence, instead adding layers of confrontation.

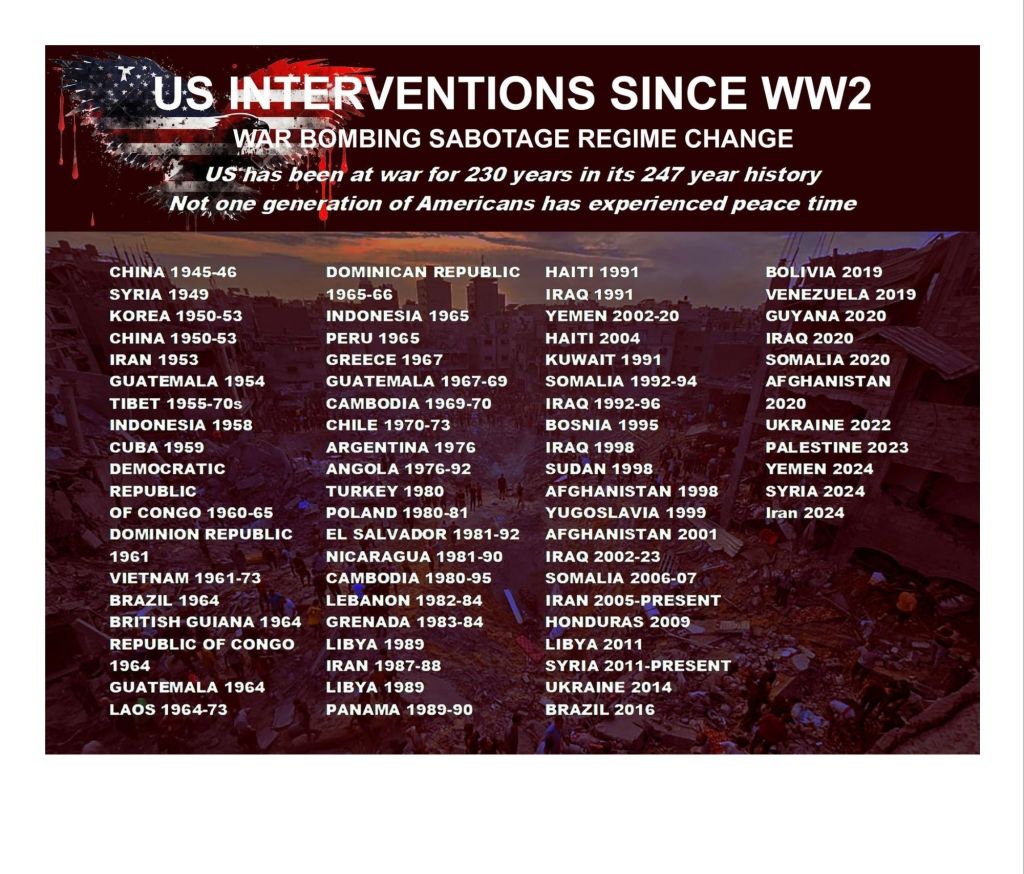

Claims that modern society progresses toward lasting peace rely heavily on selective metrics and narrow temporal frames. Steven Pinker’s decline of violence thesis drew criticism from historians and conflict researchers for undercounting indirect war deaths and structural coercion. Uppsala Conflict Data Program records show sustained levels of organised violence since the mid twentieth century despite fluctuations in battle deaths. Civil wars, foreign interventions, and transnational insurgencies replaced traditional interstate wars rather than eliminating organised violence.

The politicoeconomic structure of the global system rewards stability for dominant actors while tolerating chronic conflict elsewhere.

International financial institutions often impose austerity measures that weaken social cohesion and increase unrest within debtor states.

Resource extraction agreements favour multinational corporations while leaving host states vulnerable to armed contestation over rents and control. Such arrangements generate persistent low intensity conflicts that rarely trigger systemic reform among leading powers.

Recorded history therefore reflects not human inevitability but institutional continuity shaped by incentives, power asymmetries, and economic structures. Peace appears as an exception created by dominance, exhaustion, or temporary alignment of interests rather than moral or legal evolution. Periods without major war remain rare because mechanisms that generate conflict remain embedded within global political economy.

Structural conditions producing war continue operating across different ideological eras and technological phases.

My recommendations would perhaps include re examining arms production incentives, restructuring debt regimes, and addressing unequal resource governance mechanisms. Long term conflict reduction would require altering material interests that benefit from instability rather than relying on rhetorical peace commitments.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment