America ignores massacres in Sudan, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine but suddenly wants to “save” Christians in Nigeria.

The United States and its allies are again manufacturing a crisis abroad, this time invoking the language of religious protection in Nigeria. Each time this pattern unfolds, it begins with selective outrage and ends with strategic positioning disguised as moral duty.

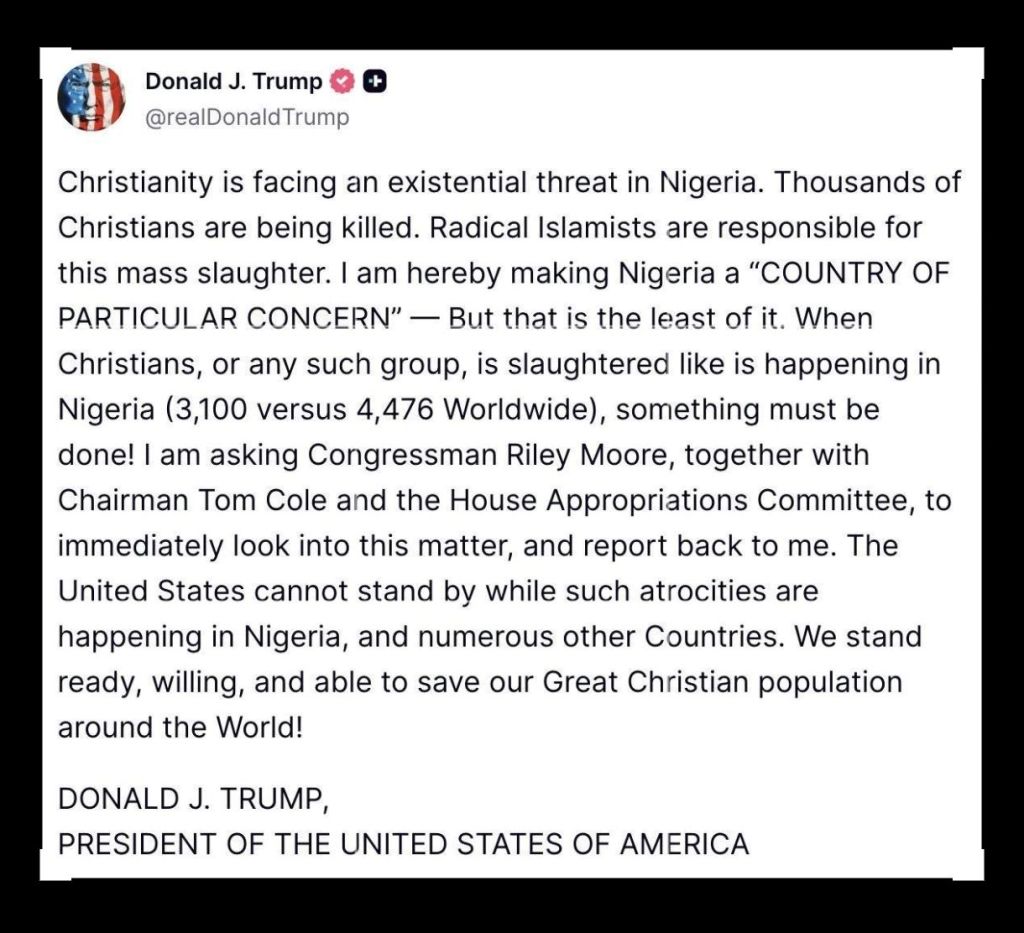

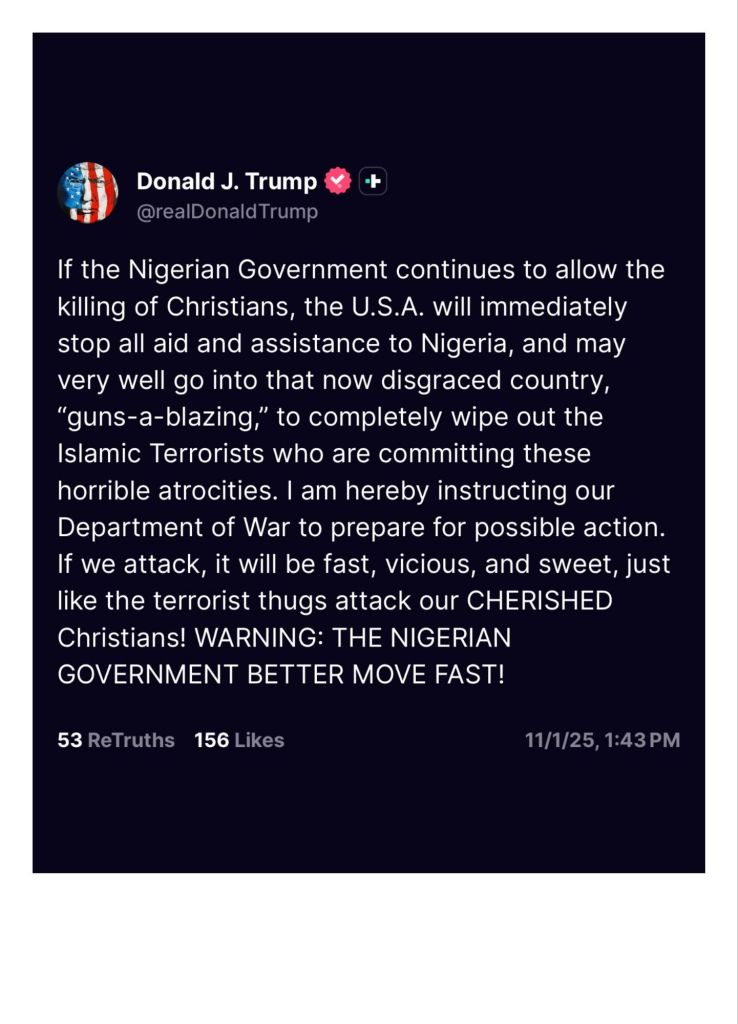

The recent noises from Washington about the persecution of Christians in northern Nigeria fit too neatly into a familiar geopolitical script that has played out in other resource-rich or strategically significant regions. When Donald Trump and others in the U.S. political establishment speak suddenly of defending Nigerian Christians, the timing and tone reveal interests far larger than faith or humanity.

“When the same governments that ignored Christian suffering in Syria or Palestine suddenly discover moral urgency in Nigeria, something deeper is always at work.”

The machinery behind such narratives has long practiced a formula that merges moral justification with material ambition. It begins by highlighting genuine suffering and turning it into a simplified story of good versus evil, Christian versus Muslim, modern versus barbaric.

That story spreads easily in Western media, where it sells sympathy and invites military or diplomatic intervention. On the ground, it rarely delivers security or peace, but it often delivers access, to mineral wealth, markets, military bases, and political leverage. Independent analysts such as Alex de Waal (African Arguments, 2023) and David Kilcullen (The Accidental Guerrilla, 2009) have described how humanitarian pretexts often mask the deeper architecture of control that defines post-Cold War interventionism.

In Nigeria, violence between communities has claimed thousands of lives across several regions, driven by competition over land, cattle, and political control. According to the International Crisis Group (2023), more than 10,000 Nigerians have been killed in farmer-herder conflicts since 2010, with the majority of deaths concentrated in the Middle Belt. Yet the framing of this conflict as primarily a religious war suits external actors who seek both moral authority and strategic advantage. It turns a complex domestic struggle into a simple international cause, one that foreign governments can exploit to justify involvement.

American policymakers and lobby networks, many aligned with evangelical or geopolitical interests, portray intervention as protection for Christians while remaining silent on similar or worse atrocities elsewhere.

“Selective moralism guided by political convenience, not genuine concern for human beings.”

The inconsistency exposes intent. In Syria, where ancient Christian communities faced displacement and death amid a proxy war fueled by global powers, Washington offered no large-scale rescue or sustained protection (UNHCR, 2022). In Lebanon and occupied Palestine, Christian populations endure hardship under economic collapse, blockades, and bombardments, yet no great Western crusade has emerged on their behalf. The pattern is selective moralism guided by political convenience, not genuine concern for human beings.

Sudan now stands as another example of this recurring strategy. The war between rival generals, financed and fueled by competing regional and international sponsors, has fractured the state and unleashed a humanitarian disaster. The United Nations reports over nine million people displaced since 2023, the largest internal displacement crisis in the world (UN OCHA, 2024). Western commentary again flirts with the language of ethnic or religious persecution, though the deeper drivers are political power, territorial control, and access to natural wealth, including gold and rare minerals. Sudan, like Nigeria, sits within a belt of resources that matter profoundly to global supply chains and military industries. The same external interests that destabilized Libya and fragmented the Sahel now hover around Sudan’s chaos, seeking leverage under the cover of humanitarian concern.

The Sahel states that resisted this playbook, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, have done so at significant cost but with clear intent. By ejecting French troops and rejecting Western tutelage, they attempted to reclaim control over their own political and economic direction. These moves have been met with sanctions, propaganda, and isolation, proof that sovereignty is tolerated only when it aligns with global interests. Their defiance exposed the depth of dependency that external actors expect and the punishment that follows any attempt to break free (ICG, 2024).

The region stretching from Nigeria through Niger and Chad to Sudan contains vast reserves of uranium, lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals essential for modern industries. Global Witness (2022) and the U.S. Geological Survey (2023) identify these territories as among the world’s most under-exploited sources of critical minerals required for defense and renewable technologies. Global powers that proclaim moral urgency in protecting civilians are often the same entities negotiating extraction contracts or securing logistical routes for resource export. The humanitarian vocabulary offers political cover for economic and military designs that would otherwise provoke outrage. Investigative reporters such as Jeremy Scahill (The Nation, 2019) and research organizations like The Sentry (2023) have documented how proxy wars and mercenary operations frequently accompany these interventions.

They show how militias are armed and funded indirectly through security assistance programs, private contractors, or covert networks operating under intelligence oversight. Once unleashed, such forces are difficult to control, creating endless cycles of instability that justify permanent foreign presence. The supposed fight for stability becomes the justification for sustained interference.

When American politicians label Nigeria a “country of particular concern,” they invoke the formal designation used by the U.S. Department of State to flag governments accused of violating religious freedom. That phrase transforms a domestic security problem into an international moral narrative and invites external management of internal affairs.

Meanwhile, the country making that judgment, the United States, is itself grappling with levels of violence that dwarf most of what it condemns abroad. In 2023, the U.S. recorded approximately 46,728 gun-related deaths, including about 17,927 homicides and 27,300 suicides (Pew Research Center, April 2023; CDC, 2024). The firearm homicide rate was 5.6 per 100,000, and the gun suicide rate 7.6 per 100,000, placing the United States far ahead of all other wealthy democracies in violent death rates. It also averages 79 gun suicides and more than 50 firearm homicides daily (CDC, 2024). That same country, which cannot secure its own citizens from routine bloodshed, presumes the moral authority to instruct others on how to protect their people. The hypocrisy is not abstract, it is statistical, documented, and institutional.

The manipulation of Nigeria’s sectarian tensions risks repeating the mistakes that shattered Libya, poisoned Syria, and bled Sudan. Every intervention justified by religion has eventually deepened division, not healed it. Once foreign militaries, intelligence agencies, and corporations embed themselves in a conflict zone, they rarely leave without reshaping local governance to their advantage. The result is a hollowed state dependent on external money, surveillance, and military training. Nigeria’s size and diversity make it a dangerous place for such experiments. Nigerians have every right to demand peace and justice, but that demand must remain theirs alone. The killings of innocent citizens are real and intolerable, yet they do not require the intrusion of powers that have repeatedly failed to protect anyone but themselves.

Religious and ethnic divisions can only be resolved by local accountability, transparent governance, and fair distribution of land and resources. Outsiders have neither the credibility nor the consistency to mediate Nigeria’s problems honestly.

“The same machinery that sells intervention as mercy has long sold wars as peace and exploitation as development.”

The United States and its partners must be judged by their record, not their rhetoric. Their selective defense of Christians in one region while ignoring massacres elsewhere reveals not compassion but calculation. Until these motives are named plainly, cycles of manipulation will continue.

Got it.

Nigeria does not need another externally scripted tragedy. It needs a state strong enough to protect all its citizens equally, a society determined to reject division, and partners who respect that sovereignty is not a gift to be granted but a right to be defended. Those who speak of humanitarian rescue while circling resource fields should be recognized for what they are: strategists, not saviors.

In the end, the truth is simple but inconvenient. The crisis narrative now building around Nigeria echoes the same rhythm heard before every intervention of the past thirty years, from Iraq to Libya, from Syria to Sudan. Each time, faith and freedom were invoked, and each time, control and extraction followed. To believe this moment is different is to ignore the history written in the ruins left behind.

Authored By: Global Geopolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

https://ko-fi.com/globalgeopolitics

References:

- Pew Research Center, What the Data Says About Gun Deaths in the U.S., April 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Vital Statistics Reports, 2024.

- International Crisis Group, Violence in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, 2023.

- United Nations OCHA, Sudan Humanitarian Update, June 2024.

- Global Witness, Critical Minerals and the New Scramble for Africa, 2022.

- U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2023.

- Alex de Waal, African Arguments: The Real Politics of the Sahel, 2023.

- David Kilcullen, The Accidental Guerrilla, Oxford University Press, 2009.

- The Sentry, Sudan’s Gold and Global Conflict Economies, 2023.

- Jeremy Scahill, The Nation, “Inside America’s Covert War in Africa,” 2019.

Would you like me to also include a short Substack summary paragraph (the one-sentence preview that appears under the title in subscriber inboxes)? I can write one that captures the argument crisply without giving away the entire piece.

Leave a comment