The legal and strategic consequences of American piracy, coercive power beyond the UN Charter, and the erosion of international maritime law

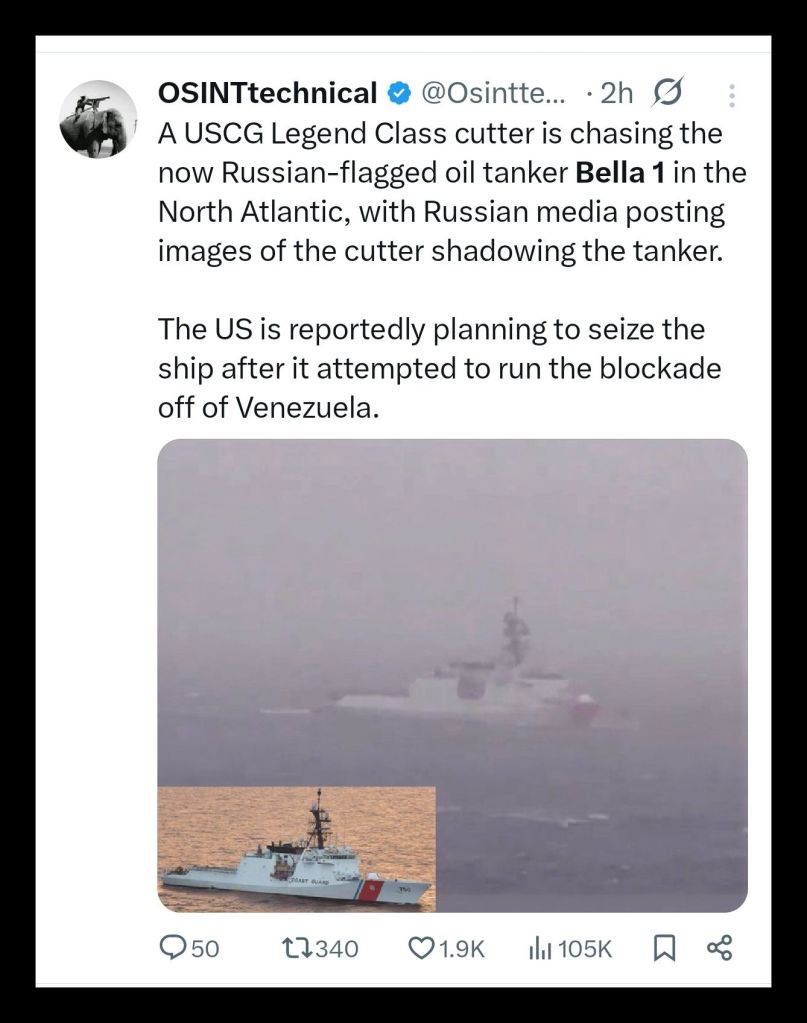

The pursuit of the oil tanker formerly known as Bella 1 illustrates a form of maritime coercion that sits outside any recognised mandate under international law. The episode concerns a sanctioned commercial vessel carrying Venezuelan crude oil, pursued across open seas by United States military and law-enforcement assets, despite the absence of authorisation from the United Nations Security Council and without a declared state of armed conflict. The matter does not hinge on sanctions compliance alone but on whether a single state may exercise de facto policing authority over global shipping lanes by force.

Bella 1 departed the Caribbean in late 2025 under pressure from an expanding United States naval presence enforcing what Washington described as a total blockade of Venezuelan oil exports. The blockade was declared unilaterally and without Security Council approval, placing it outside the framework of lawful maritime interdiction recognised by the UN Charter and the San Remo Manual on Naval Warfare. During its voyage, the vessel altered its legal status. It was renamed Marinera, registered in the Russian national vessel database, and assigned Sochi as its port of registry. Under established maritime law, a vessel sailing under a national flag enjoys the protection and jurisdiction of that state on the high seas, subject only to narrowly defined exceptions such as piracy, slavery, or unauthorised broadcasting.

Following the re-flagging, the Russian government issued a formal diplomatic note demanding that the United States cease pursuit. This step was consistent with long-standing principles codified in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which treats interference with a foreign-flagged vessel on the high seas as a violation of sovereignty unless authorised by treaty or Security Council resolution. No such authorisation exists in this case. The pursuit nonetheless continued, involving surveillance aircraft, naval coordination, and the forward deployment of special operations units.

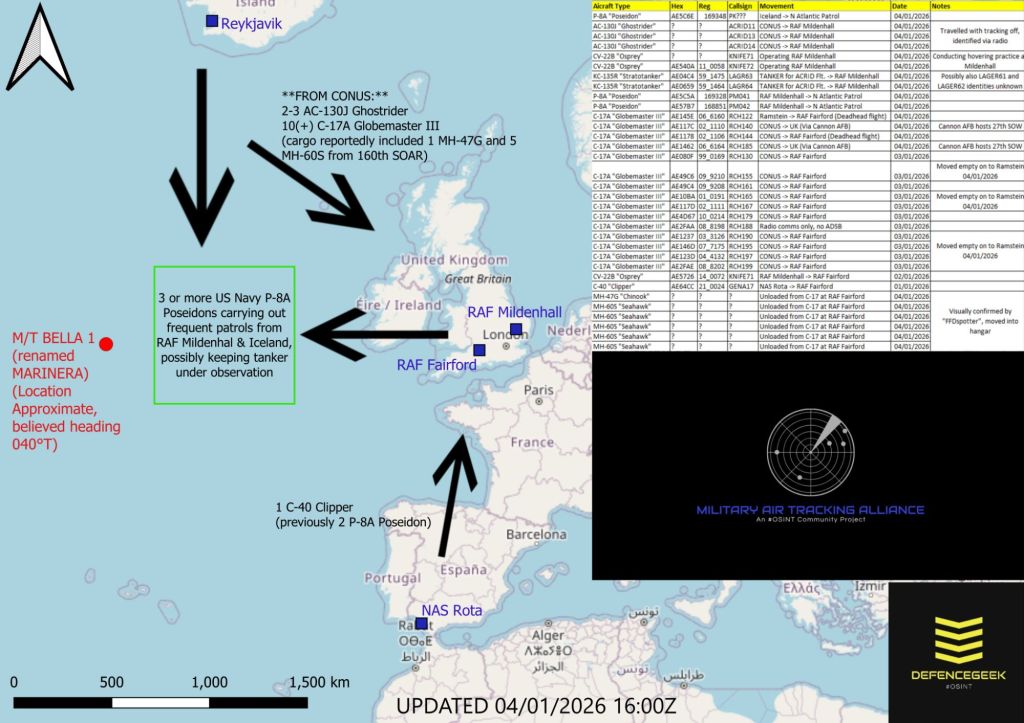

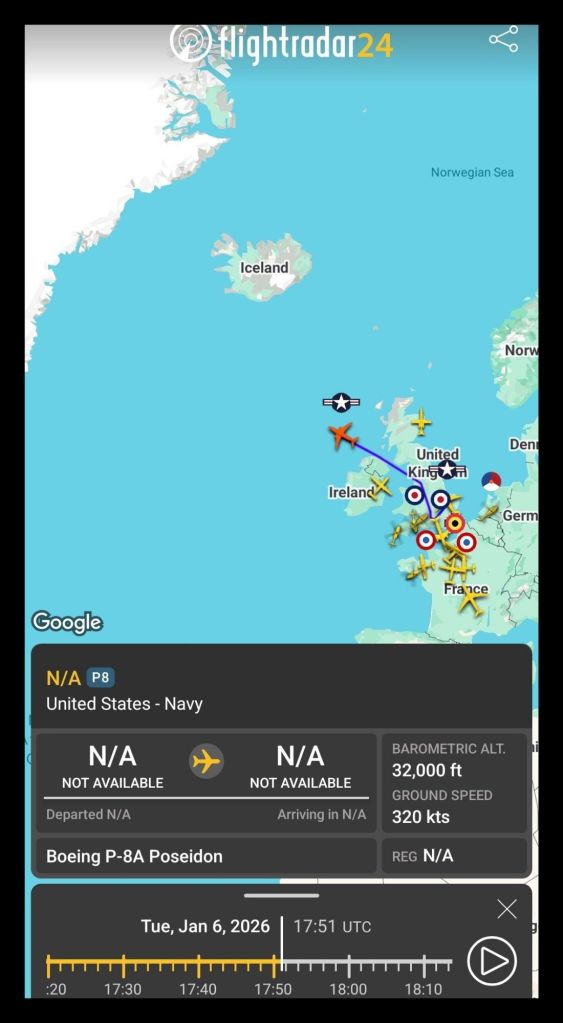

The scale of attention directed at a single tanker was striking. Maritime tracking and aviation data indicated repeated patrols by P-8A Poseidon aircraft launched from bases in Spain, the United Kingdom, and Iceland, covering vast stretches of the North Atlantic. At one point, three such aircraft operated simultaneously near the Faroe Islands, maintaining near-continuous coverage of Marinera’s route. This level of military surveillance would normally accompany preparations for boarding or seizure rather than routine monitoring.

Additional deployments reinforced this assessment. Aircraft and rotary assets associated with United States special operations forces were transferred to British bases, including AC-130J gunships, CV-22B tilt-rotors, and MH-47G helicopters operated by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. This unit has a documented role in maritime interdiction and forced boarding operations. No public exercise notifications or alliance statements accompanied the deployment. Silence from official channels contrasted with the scale and specificity of the movements.

The legal justification advanced by Washington rests on domestic sanctions enforcement. United States authorities argue that prior involvement in Iranian and Venezuelan oil trading renders vessels such as Marinera subject to seizure under United States law. That position extends domestic jurisdiction far beyond territorial waters and into the global commons. International law does not recognise unilateral sanctions as a basis for boarding foreign-flagged vessels on the high seas. Alfred de Zayas, former UN Independent Expert on international order, described such practices as a revival of gunboat diplomacy under administrative cover. Legal scholars at Cambridge and Leiden have similarly noted that extraterritorial sanctions enforcement lacks standing without multilateral consent.

Characterisation of these vessels as part of a “shadow fleet” does not alter the legal position. The term has no standing in maritime law and functions as a political label rather than a juridical category. Transporting oil for sanctioned states does not constitute piracy, which international law defines narrowly as violent robbery at sea for private ends. Nor does it fall under universal jurisdiction crimes. Absent a Security Council mandate, seizure attempts rely on raw force rather than law.

Russian handling of the Marinera case reflects a deliberate strategic response rather than an ad hoc manoeuvre. By granting flag protection mid-voyage and formally asserting jurisdiction, Moscow forced the issue into the diplomatic and legal domain. The move tested whether flag state protection remains operative when challenged by a militarily superior power. Analysts such as Glenn Diesen have argued that erosion of this principle would render maritime law subordinate to power hierarchy, undermining smaller and medium shipping states as much as sanctioned ones.

Speculation that Russia intends to extend similar protection to other sanctioned tankers aligns with broader patterns in global trade fragmentation. Sanctions imposed on Russia, Iran, and Venezuela have encouraged parallel logistics networks operating outside Western insurance, financing, and port access systems. Attempts to suppress these networks through force risk turning commercial shipping into a theatre of military confrontation. The Gulf of Finland incident, where Finnish special forces boarded a tanker without a UN mandate, points to a widening zone of contestation in European waters.

The involvement of NATO surveillance assets adds another layer of concern. Tracking operations near Ireland, Iceland, and Norway occurred far from any declared theatre of hostilities. Use of alliance infrastructure to support unilateral interdiction blurs the line between collective defence and national enforcement action. It also places non-belligerent states in proximity to a potential confrontation between nuclear-armed powers over a commercial vessel.

Statements attributed to United States officials indicate a preference to seize rather than sink the tanker. That distinction does little to resolve the legal breach. Boarding by force against the will of the flag state constitutes an act of aggression under General Assembly Resolution 3314, which defines aggression to include blockade and attack on merchant shipping. The fact that such actions are framed as law enforcement rather than warfare does not alter their substance.

The broader context includes the capture of Venezuelan leadership by United States forces and a series of strikes on vessels in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific, reportedly resulting in significant loss of life. These actions form part of an escalating pressure campaign aimed at control over Venezuelan resources rather than compliance with international adjudication. Public statements by United States leadership demanding the return of oil and other assets reinforce this interpretation. The language mirrors nineteenth-century practices of maritime seizure and indemnity enforcement rather than post-1945 collective security norms.

From a politico-economic perspective, the Marinera episode exposes a contradiction at the core of the current sanctions regime. Global energy markets depend on freedom of navigation and predictable legal treatment of shipping. Turning enforcement into a matter of aerial surveillance and special forces raids introduces uncertainty that raises insurance costs, reroutes trade, and incentivises further concealment rather than compliance. Economists studying sanctions effectiveness, including Richard Nephew and Agathe Demarais, note that excessive coercion often accelerates the formation of alternative systems rather than restoring leverage.

The silence of international institutions on this episode carries consequences. Failure to respond signals acceptance of a precedent where maritime law yields to unilateral enforcement backed by military power. Smaller states and neutral shipping registries would bear the long-term cost, as flag protection becomes conditional on geopolitical alignment. The erosion of legal equality at sea mirrors earlier erosion on land through sanctions and proxy warfare.

What emerges from the Marinera case is not an isolated enforcement action but a test of whether international law retains operational force in global commerce. The actions taken against this tanker resemble piracy in functional terms, defined not by private intent but by seizure without lawful authority. Labeling such conduct as sanctions enforcement does not alter its effect on the integrity of the maritime order.

If the supranational bodies worked in the interests of the text in their charters, I would recommend an emergency review by the United Nations General Assembly of unilateral maritime interdiction practices would clarify legal boundaries. Flag states should coordinate diplomatic responses to unlawful boardings to reinforce collective norms. International maritime insurers and classification societies should condition coverage on adherence to UN-mandated enforcement only. These steps would reduce escalation risks and restore legal predictability without endorsing any sanctioned trade.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment