Resource control, dollar primacy, and the costs of discarding realism

The recent pattern of United States behaviour towards Venezuela, Cuba, Colombia, Iran, and even Greenland reflects a continuity in coercive statecraft rooted in resource control, financial dominance, and regime pressure rather than isolated rhetorical excess. The kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, described in United States legal proceedings as a capture operation, fits within a longer history of extraterritorial enforcement actions justified through domestic legal frameworks rather than international law. Former United Nations Special Rapporteur Alfred de Zayas has previously warned that such actions against Venezuela constitute collective punishment and unlawful intervention, a position echoed by multiple independent international law scholars at Geneva and Oxford.

Venezuela occupies a central place in this pattern due to its strategic resource base, including significant oil reserves, gold holdings, and other mineral assets whose control directly affects global commodity markets and the dollar-based financial system. Economist Michael Hudson has argued that United States foreign policy increasingly treats sovereign resource holdings as collateral within a declining imperial financial order, especially when those resources underpin alternative trade arrangements outside dollar settlement systems. The removal or neutralisation of leadership figures therefore functions as a means of restoring compliance rather than resolving political disputes.

The seizure of Venezuelan assets abroad, including gold reserves held in the United Kingdom, already established a precedent where sovereignty was subordinated to financial and political alignment. Legal scholar Francis Boyle has described such measures as economic warfare conducted under colour of law, bypassing United Nations mechanisms entirely. The reported objective of removing physical control over Venezuelan silver and related reserves aligns with this broader framework of asset extraction rather than governance reform.

The extension of threats towards Cuba follows a similar logic, despite decades of sanctions having failed to produce regime collapse. Former Cuban diplomat Carlos Alzugaray has consistently argued that United States hostility towards Havana persists not because of Cuban actions but because of its symbolic resistance to hemispheric compliance. Statements suggesting that Cuba is next indicate an escalation from economic pressure towards overt security coercion, a move that would destabilise an already fragile Caribbean security environment.

Colombia represents a more complex case, as it has historically functioned as a key United States partner in Latin America through military cooperation, intelligence sharing, and counter-narcotics programmes. The emergence of threats directed at Colombian President Gustavo Petro signals a shift from alliance management towards conditional loyalty enforcement. Petro’s public rejection of alignment against Venezuela and his opposition to expanded United States military basing have placed Colombia outside the accepted policy corridor. Political scientist Atilio Borón has noted that Washington’s tolerance for deviation among allies narrows significantly during periods of perceived imperial contraction.

The reference to Greenland, often dismissed as rhetorical, reflects a longstanding strategic interest tied to Arctic resources, rare earth minerals, and emerging shipping routes. Danish defence analysts have acknowledged that United States interest in Greenland intensified following China’s investment activity in Arctic infrastructure. Control over such territories strengthens access to strategic minerals critical for advanced weapons systems and technological supply chains, reinforcing economic dominance under conditions of great power competition.

Iran remains a parallel theatre where similar methods have been applied through sanctions, covert operations, and targeted assassinations. Former CIA analyst Ray McGovern has argued that Iran’s refusal to submit to United States financial oversight, combined with its integration into Eurasian trade structures, places it within the same strategic category as Venezuela. The question raised about operational capability in Iran reflects concern over escalation thresholds rather than moral restraint.

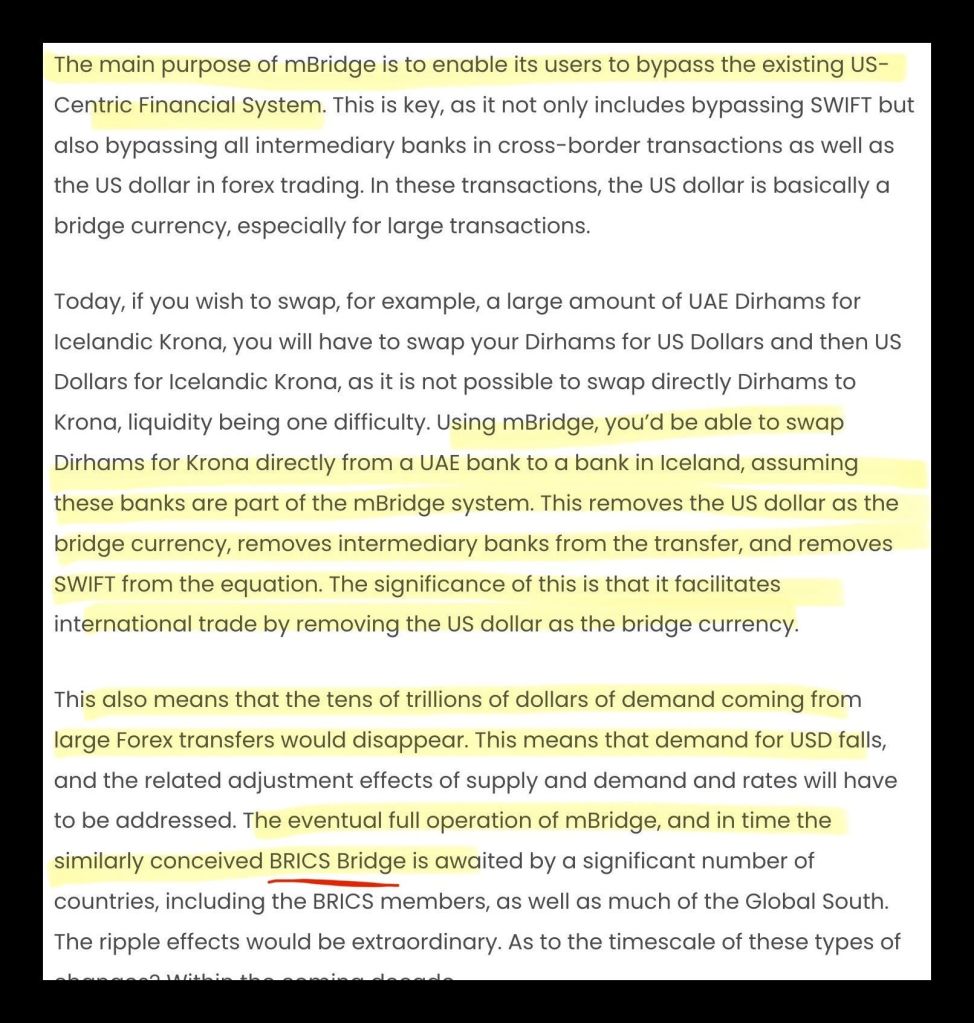

Underlying these cases lies a structural imperative tied to sustaining dollar primacy. Control over energy, metals, and trade routes directly supports the reserve currency system by enforcing external demand and limiting alternatives. Economist Yanis Varoufakis has described this arrangement as a global recycling mechanism maintained through political and military pressure rather than market efficiency. When states attempt to exit this system, coercive responses follow with increasing speed.

The absence of clear post-intervention planning further reinforces the view that these actions prioritise immediate compliance over long-term stability. The repeated question regarding succession planning after leadership removal echoes failures observed in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan, where regime collapse produced systemic instability without achieving stated objectives. Former US diplomat William Polk has argued that such outcomes reflect institutional memory loss rather than miscalculation.

International response mechanisms appear largely symbolic, with statements of concern replacing enforcement of legal norms. The erosion of multilateral constraint allows powerful states to act unilaterally while framing actions within domestic legal narratives. This dynamic weakens international law as a practical restraint and incentivises pre-emptive alignment among smaller states seeking protection.

The cumulative effect of these policies increases global fragmentation and accelerates the formation of alternative economic and security blocs. Russian analyst Glenn Diesen has observed that coercive Western strategies drive affected states towards deeper cooperation with China and Russia, reinforcing multipolar structures rather than restoring unipolar control. Each intervention therefore produces diminishing returns while expanding systemic risk.

Policy recommendations, if any are to be considered, would require a return to negotiated settlement mechanisms grounded in international law, asset restitution, and recognition of sovereign economic choices. Without such shifts, the pattern of escalation will likely persist, further undermining stability and accelerating the erosion of the existing global order. The trajectory described above also marks a clear abandonment of classical realist restraint in favour of ideological and financial compulsion. Traditional realism prioritised balance of power, predictable interests, and negotiated accommodation between rival states, even under conditions of hostility. Current policy behaviour instead reflects moralised enforcement, domestic legal extraterritoriality, and economic punishment untethered from achievable strategic equilibrium. Scholars such as John Mearsheimer have warned that discarding realism removes the stabilising logic that once limited escalation between major powers. Without realist discipline, policy becomes reactive, personalised, and structurally prone to overreach, increasing the likelihood of uncontrollable conflict rather than managed competition.

Classical realism, as developed by thinkers such as Hans Morgenthau and later refined by Kenneth Waltz, begins with the assumption that power matters, but it does not argue for unlimited coercion or arbitrary domination. Realism treats power as something to be managed carefully because excessive use of force creates counter-balancing coalitions, drains resources, and produces instability that ultimately weakens the stronger actor. The central realist concern is not moral restraint but strategic self-preservation over time.

In realist theory, stronger states impose their will selectively and with restraint, guided by clear interests and an awareness of limits. Realists argue that law-of-the-jungle behaviour is self-defeating because it encourages resistance, alliances among weaker states, and long-term erosion of influence. George Kennan, often cited as a realist architect of containment, repeatedly warned that ideological crusades and punitive excess would undermine American power rather than secure it.

What is being abandoned in the behaviour discussed earlier is precisely this restraint. The use of sanctions, asset seizures, leadership targeting, and extraterritorial legal claims without a clear balance-of-power logic departs from realism and moves closer to ideological enforcement or financial imperialism. These actions do not stabilise hierarchies; they destabilise them by forcing weaker states into alternative alignments.

Realism accepts inequality of power as a fact of international politics, but it rejects the idea that unchecked domination is sustainable or rational. In that sense, realism is not the law of the jungle, but a theory about how predators that overhunt eventually starve.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment