Extraction without Accumulation: The Political Economy of Zambia’s Underdevelopment

Zambia’s position within the global minerals economy conforms closely to John Perkins’ description, reflecting extraction structured through political control, legal asymmetry, and external economic power. Perkins wrote that modern economic structures operate “to convince leaders of underdeveloped countries to accept huge loans, so that even more resources and much of the decision-making power of said countries come under the control of outside interests.” Copper, gold, and associated minerals extracted from Zambian territory generate substantial revenues within global commodity markets and corporate balance sheets while the producing country remains fiscally constrained and structurally dependent.

This configuration arose through decades of political and economic arrangements designed to prioritise external accumulation over domestic capital formation. Control over ownership, pricing, taxation, and policy space has been progressively shaped to favour foreign interests, leaving formal sovereignty intact while substantive economic autonomy remains limited, a dynamic Perkins identifies as central to undermining economic independence. Walter Rodney observed that underdevelopment is not an absence of development but the result of a historical process through which wealth is transferred outward while poverty is reproduced internally.

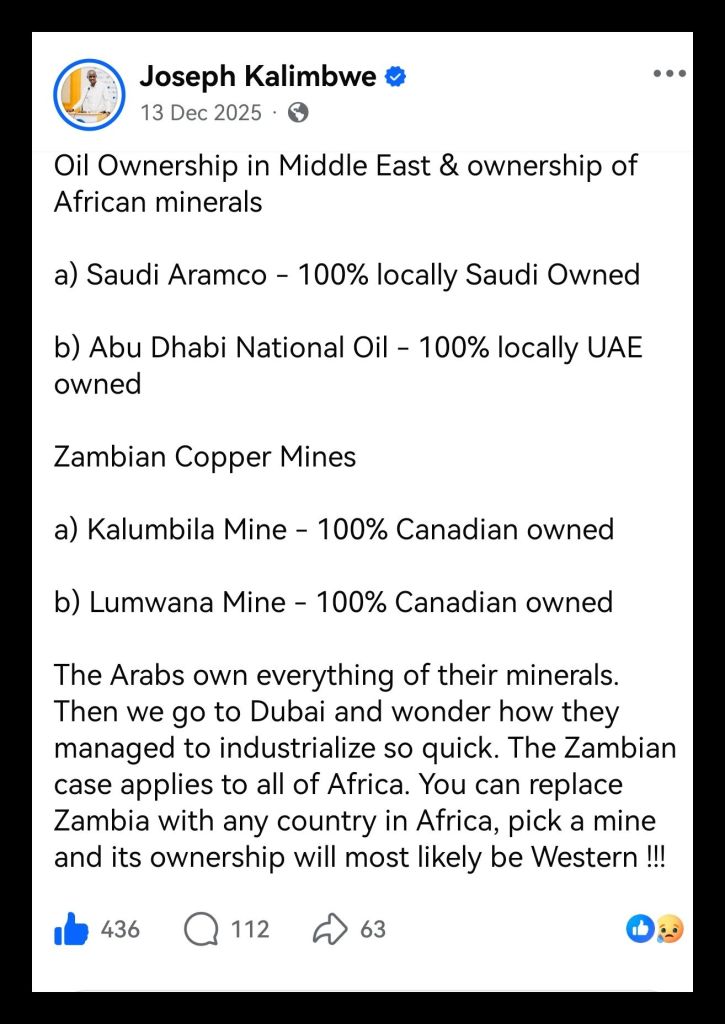

Copper production in Zambia operates within ownership structures established after the early 1990s privatisation period, when state mining assets were transferred almost entirely into foreign hands. Several major copper mines, including Lumwana and Kalumbila, operate under full foreign ownership with no Zambian equity participation. Revenue flows to the state are therefore limited to royalties, profit taxes subject to aggressive minimisation, wages, and discretionary corporate social responsibility expenditures. Ownership, pricing power, and export control remain external.

Copper prices rose sharply during recent years, exceeding thirteen thousand United States dollars per metric tonne. One major Canadian mining firm operating in Zambia reported production of 181,000 tonnes of copper in 2025, generating revenues exceeding $2.3 billion. Comparable production figures across other foreign-owned mines imply aggregate export revenues far exceeding the Zambian state’s annual budget. Despite this extraction scale, Zambia continues to rely on external borrowing to finance roads, airports, hospitals, and basic infrastructure. This fiscal contradiction reflects the gap between gross export value and domestic value capture. Economists such as Ha-Joon Chang and Samir Amin describe this as structural underdevelopment, where peripheral economies supply raw materials without retaining surplus for domestic accumulation. Zambia conforms closely to this pattern.

The legal architecture governing Zambia’s mining sector reinforces this imbalance. Investment treaties signed during liberalisation restrict the state’s ability to alter tax regimes without triggering compensation claims or arbitration. Tax treaties reduce withholding taxes and limit capital controls, allowing profits to be repatriated with minimal friction. Trade treaties impose tariff discipline while permitting commodity exports to flow outward without reciprocal industrial development obligations. Legal scholar Gus Van Harten has documented how such treaties shift risk from investors to host states while narrowing democratic policy space.

Transfer pricing practices further erode Zambia’s tax base. Copper is frequently sold to affiliated trading entities in low tax jurisdictions at below-market prices, with profits realised downstream in Switzerland or other trading hubs rather than in Zambia. The OECD has acknowledged the scale of base erosion through commodity mispricing, though enforcement remains limited where political leverage is weak. Switzerland plays a central role within this system. A significant proportion of Zambian copper exports are marketed through Swiss commodity trading houses, despite Switzerland possessing no copper mines. In recent years, copper valued at nearly $4 billion originating from Zambia was routed through Switzerland. Swiss unemployment remains near 3 percent, while mining towns in Zambia such as Mufulira experience unemployment exceeding 70 percent, reflecting asymmetrical value chains rather than differences in effort or productivity.

The political economy sustaining this arrangement depends on elite capture within Zambia. Leadership reliant on foreign capital often internalises investor priorities, framing national development in terms compatible with external interests. Political scientist Jeffrey Winters describes this as oligarchic accommodation, where policy stability for capital outweighs distributive outcomes for citizens. Zambia’s post-independence political discourse has focused on basic service provision rather than structural transformation, reflecting constrained fiscal capacity and limited policy autonomy. This stagnation contrasts sharply with oil-producing states in the Arab world. Countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia retained sovereign ownership over hydrocarbon resources, negotiated production sharing arrangements, and accumulated national capital through state-owned enterprises. Western states accommodated these arrangements due to geopolitical dependencies and energy security considerations. Zambia and comparable African states were not afforded similar latitude during liberalisation.

Historical evidence from Zambia demonstrates that alternative approaches produced materially different outcomes. During the mid-2000s, the government introduced a windfall tax targeting mining profits during high commodity prices. Mining companies publicly threatened withdrawal, though no major exits followed due to immobile assets. Government revenues increased from $300 million to $800 million within a single year, with the windfall tax contributing roughly $400 million directly to the treasury. Macroeconomic indicators improved during this period. The Zambian kwacha strengthened, domestic firms such as Ndola Lime expanded operations, and fiscal dependence on external borrowing declined. Following the president’s death, the windfall tax was rapidly repealed, and mining revenues fell to approximately $100 million the following year, confirming the fiscal sensitivity of policy design. Economist Joseph Stiglitz has repeatedly argued that credible taxation regimes, not ownership flight, determine long-run investment behaviour in extractive sectors.

Infrastructure usage provides another illustration of unequal value extraction. Copper trucks leaving Zambia carry cargo worth hundreds of thousands of dollars while contributing minimal road usage fees. Proposals to impose modest transit charges equivalent to a small fraction of cargo value would generate substantial daily revenue for domestic infrastructure maintenance. Political resistance reflects investor influence rather than economic irrationality. The cumulative effect of these mechanisms is developmental paralysis. Zambia has remained focused on primary education access, water provision, and road repair for over six decades. Political debate continues to centre on survival needs rather than technological development or industrial upgrading. Meanwhile, countries benefiting from Zambian mineral flows invest in advanced manufacturing, scientific research, and geopolitical influence. Walter Rodney described this dynamic as underdevelopment produced through extraction rather than absence of resources.

Comparable cases offer evidence that reversal remains possible. Malaysia’s early 1980s intervention in foreign plantation ownership, referenced as the Guthrie Dawn Raid, demonstrated how coordinated political action could reclaim strategic assets without economic collapse. Subsequent industrialisation and employment outcomes support the argument that sovereignty over productive assets determines long-term development trajectories. Zambia’s current condition reflects political choices constrained by external legal regimes and internal elite incentives. Minerals extracted from Zambian soil continue to finance prosperity elsewhere while domestic communities remain excluded from meaningful participation in the value chain. This outcome aligns with long-standing theories of dependency advanced by Andre Gunder Frank and reinforced by economists at SOAS and the University of Cape Town.

Reversing this pattern requires structural change grounded in full political and economic sovereignty rather than incremental regulatory adjustment. Policy measures such as partial state equity participation in mining assets, restoration of progressive taxation linked directly to commodity price cycles, renegotiation of asymmetrical tax treaties, and strict enforcement of transfer pricing rules remain necessary but insufficient without control over political decision making itself. Frantz Fanon warned that national independence without economic control merely replaces colonial administrators with local intermediaries serving external interests. Sovereign authority over logistics, mineral processing, export marketing, and strategic infrastructure would materially increase domestic value capture while reducing external leverage over fiscal policy. Samir Amin argued that meaningful development requires delinking from global systems enforcing unequal exchange rather than reforming structures designed to extract surplus. Achieving delinking requires protection of political institutions from foreign influence through transparent campaign financing laws, restrictions on revolving doors between political office and extractive capital, and security oversight over strategic sectors. Kwame Nkrumah described neocolonialism as control exercised through economic means, where foreign interests shape domestic policy while maintaining formal independence. Historical cases across Asia and parts of Latin America demonstrate that assertive sovereignty over natural resources, combined with internal political discipline and security of decision making, precedes durable economic transformation. Without insulation of leadership and political systems from foreign economic pressure, technical reforms remain vulnerable to reversal, as Zambia’s experience after the windfall tax removal demonstrates.

Development outcomes in resource-rich countries correlate more strongly with ownership structures and policy autonomy than with geological endowment, a relationship well established in comparative political economy. Zambia’s experience since 1964 illustrates this dynamic with unusual clarity. Copper has remained the backbone of the economy for six decades, frequently accounting for more than seventy percent of export earnings and the majority of foreign exchange inflows, yet this dependence has not translated into sustained capital accumulation or structural transformation. Between 1965 and 1975, copper contributed close to ninety-five percent of export earnings and approximately forty-five percent of government revenue, with the mining sector representing over one-third of GDP. Although global price shocks in the late 1970s reduced fiscal receipts, copper continued to dominate the external sector. Following privatisation in the 1990s, mining still accounted for roughly seventy percent of exports into the 2000s while contributing only ten to fifteen percent of GDP, reflecting weak domestic linkages. In 2024, copper exports were valued at approximately USD 7.6 billion, yet fiscal returns remained modest relative to export value.

IMF and World Bank assessments identify persistent revenue leakages as a central constraint. IMF balance-of-payments analysis indicates that between 2020 and 2021, an estimated fifty to ninety percent of copper export earnings were not repatriated to Zambia, reflecting profit shifting, offshore retention, and transfer pricing practices. Earlier IMF programme reviews documented capital outflows equivalent to as much as twenty percent of GDP in some years, contributing to chronic foreign-exchange shortages and repeated recourse to external borrowing despite high export volumes. Cumulatively, Zambia has exported tens of millions of tonnes of copper since independence. Even under conservative long-run pricing assumptions, gross export values plausibly exceed several hundred billion US dollars over six decades. Against this scale, the state captured only a limited share through royalties, wages, and unstable tax instruments, while relinquishing ownership, pricing power, and downstream processing capacity. Today, foreign firms control more than seventy percent of copper production, and domestic value addition remains minimal, with exports dominated by unprocessed concentrate and cathodes.

The fiscal consequences are visible in Zambia’s development outcomes. Despite prolonged extraction, infrastructure investment, industrial diversification, and human capital accumulation remain constrained, while public finances are characterised by debt dependence and IMF-supported stabilisation programmes. By contrast, resource-exporting states that retained sovereign control over extractive assets and fiscal regimes converted resource rents into national wealth funds, infrastructure, and diversified productive capacity within comparable or shorter time horizons. IMF comparative studies confirm that countries with stable resource taxation and state participation achieve higher domestic retention and lower volatility than those reliant on investor-led extraction.

Zambia’s trajectory therefore reflects institutional and political choices rather than resource scarcity. Policy reversals, including the removal of windfall taxes in the late 2000s despite unchanged production levels, demonstrate the fragility of revenue mobilisation in the absence of protected policy autonomy. Changes in fiscal regimes have consistently produced immediate shifts in mining revenues, underscoring that outcomes are driven by governance and ownership structures rather than technical constraints. The central lesson of Zambia’s post-independence experience is that formal sovereignty without economic control produces persistent underaccumulation. Copper wealth has generated substantial value, but much of it has been realised abroad through corporate balance sheets and financial centres rather than within the domestic economy. The resulting gap is measured not only in foregone revenue, but in lost decades of capital formation and institutional development.

Reversing this pattern requires reasserting sovereignty over resource governance, stabilising fiscal regimes, strengthening ownership and value-capture mechanisms, and insulating economic policy from external pressures. Without these structural shifts, continued mineral extraction will reproduce export dependence and fiscal fragility rather than deliver development. Zambia’s history since 1964 demonstrates both the scale of what has been lost and the institutional conditions required to prevent its recurrence.

N.B. There is a longer analysis, an extended version via substack

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

Thank you for visiting. This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support. You can support by way of a cup of coffee:

https://buymeacoffee.com/ggtv or

https://ko-fi.com/globalgeopolitics

References

Ake, Claude. Democracy and Development in Africa. Brookings Institution, 1996.

Chang, Ha‑Joon. Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. Bloomsbury, 2008.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). Zambia: Third Review Under the Extended Credit Facility Arrangement. IMF Country Report No. 23/002.

International Monetary Fund, 2023.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). Zambia: Selected Issues. IMF Country Report No. 19/002. International Monetary Fund, 2019.

IFC (International Finance Corporation). Zambia Country Private Sector Diagnostic. World Bank Group / IFC, 2024.

Perkins, John. Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. Berrett‑Koehler Publishers, 2004.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle‑L’Ouverture Publications, 1972.

World Bank. Zambia Economic Brief: Managing Windfalls. World Bank Group, 2021.

World Bank. Zambia – Managing Mineral Wealth for Development. World Bank Group, 2016.

Leave a comment