Why Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s legal jeopardy marks a turning point for Britain’s Monarchy exposing institutional vulnerability, public distrust, and the limits of hereditary immunity

The arrest of Prince Andrew, legally Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, on suspicion of misconduct in public office over his links to Jeffrey Epstein marks a rare moment in British constitutional history. Officers from Thames Valley Police detained a man in his sixties at Wood Farm on the Sandringham estate, acting on allegations that he passed confidential government documents to the late financier while serving as a United Kingdom trade envoy, according to reporting on the incident. The use of the criminal law against a former senior royal figure touches questions about the scope of elite immunity and the application of ordinary legal standards across centuries of inherited privilege.

A number of media commentators, including some from the BBC, described Prince Andrew’s arrest as the first royal arrest in centuries, suggesting the last such event dated back to Mary, Queen of Scots in 1556; this framing ignored a more pertinent historical precedent. The last British monarch to be formally arrested and put on trial was King Charles I during the English Civil War, when parliamentary forces detained him in 1647, tried him for high treason and subsequently executed him in 1649, an event that decisively ended his reign and led to a temporary abolition of the monarchy. This omission matters because treating centuries‑old selective examples as authoritative over more definitive constitutional history obscures how dramatically power structures can shift and what legal accountability has meant in past conflicts between sovereign authority and law.

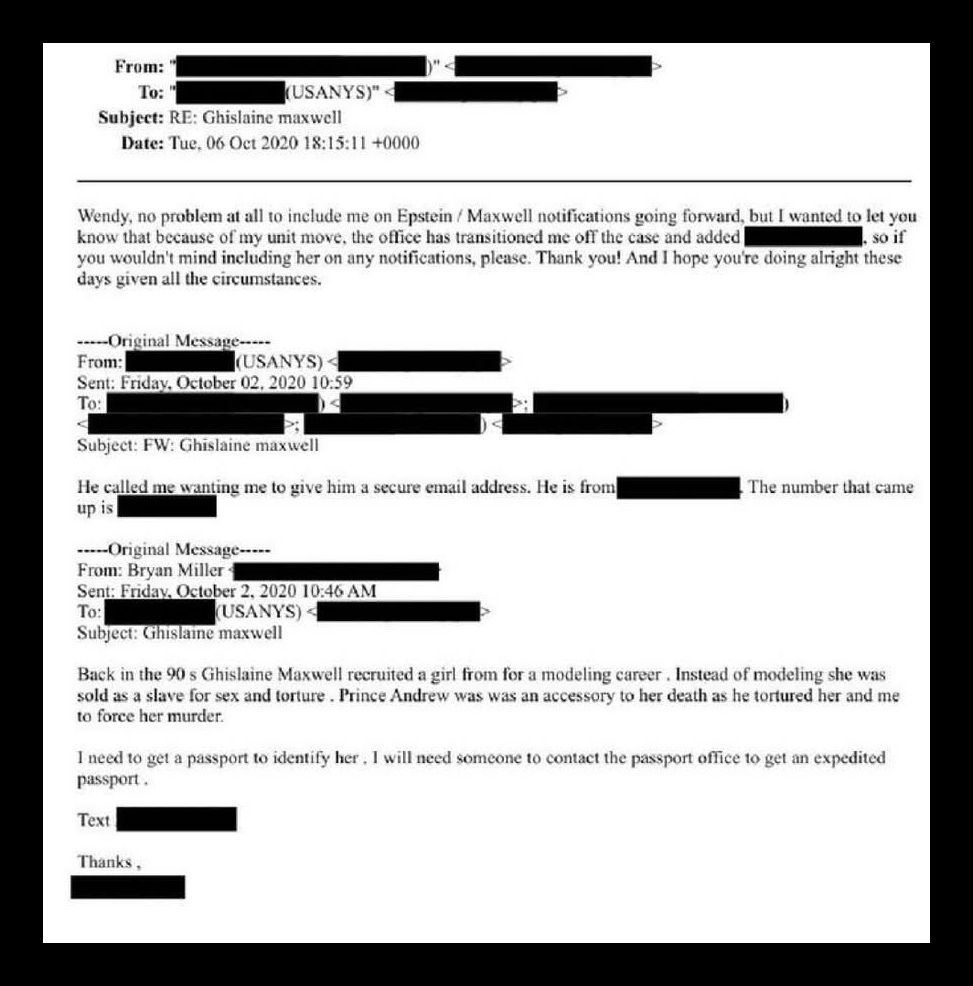

The charge of misconduct in public office does not allege sexual trafficking or assault, despite public outrage over Andrew’s association with Epstein. Instead, prosecutors appear to be pursuing a legally defined breach of duty grounded in documentary evidence that can be reliably tested in court. Legal scholars note that while moral gravity and public disgust draw headlines, prosecutors proceed where rules of evidence and statutory definitions provide a stable path to conviction. This basic procedural logic explains why an offence that sounds technical can become the vehicle for challenging entrenched power.

Experience from other jurisdictions shows that powerful individuals seldom fall at the peak of public moral outrage. In South Africa, former President Jacob Zuma survived years of allegations including sexual assault and state capture linked to the Gupta family before being imprisoned in 2021, not for the original allegations, but for contempt of the Constitutional Court after refusing to abide by a judicial order. South African commentators observed that incremental and procedural enforcement of law, rather than sudden spectacle, ultimately delivered accountability. Similarly, when the son of Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda committed a serious crime in Lusaka, Kaunda permitted the judiciary to proceed without executive interference, underscoring the ideal that even powerful kin must face legal consequences when evidence is clear.

Comparable patterns of elite accountability are visible in continental Europe, where entrenched political figures eventually faced legal consequences through institutional processes. Italy’s former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, after decades of legal challenges and allegations of wrongdoing, was convicted of tax fraud in 2013 by the Supreme Court of Cassation and sentenced to a four‑year term, largely served through community service given his age, and banned from public office for a period. The conviction stemmed from a long‑running case involving tax evasion relating to the manipulation of media rights at the Mediaset television empire, and the court upheld the sentence against appeal. Although Berlusconi avoided long‑term imprisonment, his conviction represents a measure of legal consequence enforced against one of post‑war Europe’s most powerful political figures. In France, former Prime Minister François Fillon was found guilty of embezzling public funds when he paid his wife and children for parliamentary work they did not perform, a scandal that ended his presidential campaign and led to a suspended sentence and prohibition from public office. These cases demonstrate that European legal institutions, like their African counterparts, can impose accountability upon political elites, often via procedural rather than headline-grabbing mechanisms.

In the United States, the legal and political fallout from the Epstein files has exposed deep divisions over accountability and transparency. Congress passed the Epstein Files Transparency Act to compel the Department of Justice (DOJ) to release records relating to the late financier’s investigations. The DOJ initially released a first tranche of heavily redacted materials on 19 December 2025, but criticism quickly emerged from both sides of the aisle that the release failed to meet the law’s requirements and fell far short of full public disclosure. Mass redactions, pages completely blacked out, and the initial disappearance of documents from the public repository drew bipartisan censure as inconsistent with the statute’s intent for open disclosure. Critics noted that more than 500 pages were entirely blacked out, and less than one per cent of the total potentially responsive material had been publicly released at that stage.

Representative Thomas Massie, one of the lead authors of the Transparency Act, accused Attorney General Pam Bondi’s Justice Department of “criminal negligence” over its handling of the release. Massie pointed to documents in which alleged predators’ names were redacted while the identities of alleged victims were exposed, arguing that the department had violated the letter and spirit of the law by failing even to protect victim privacy properly. Massie took the unusual step of pressing these criticisms directly at Bondi during a congressional hearing, where he described the redaction practices as “bigger than Watergate” and emphasised that the department’s conduct suggested deliberate misclassification rather than accidental error.

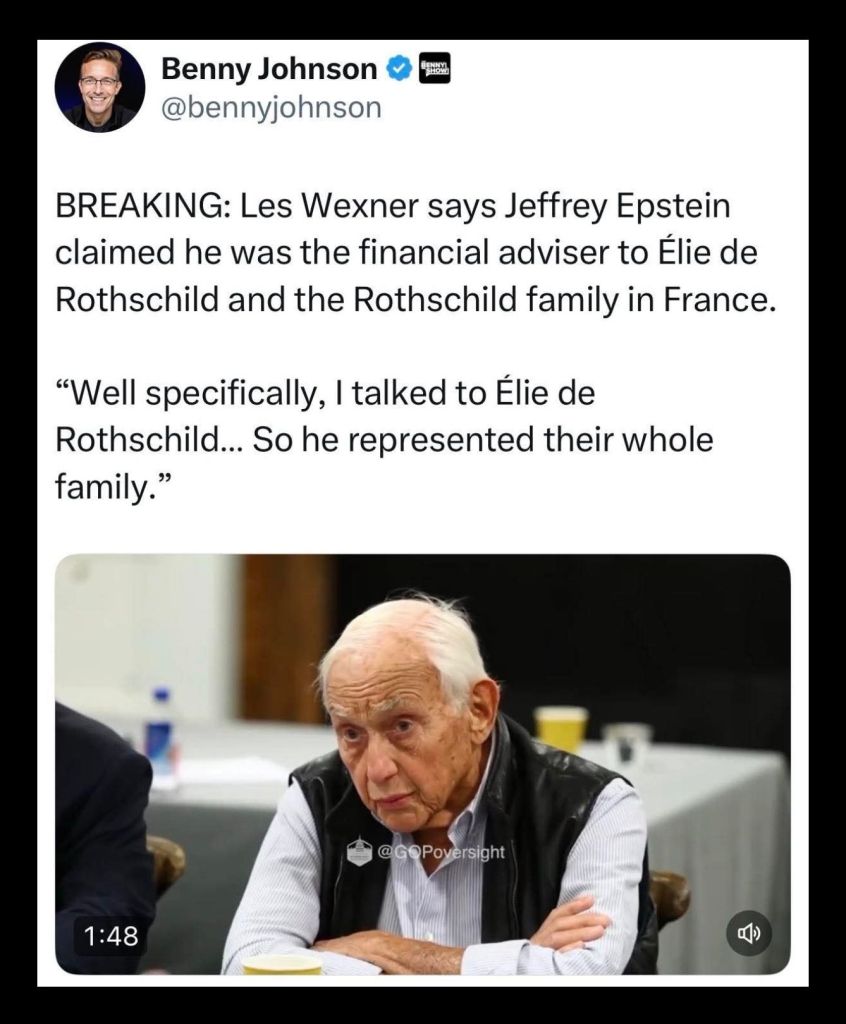

Massie and Representative Ro Khanna publicly reviewed unredacted files in a secure DOJ reading room and thereafter read aloud on the House floor the names of powerful men whose identities had been withheld from the public release, including billionaires such as Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem and Leslie Wexner. They argued that redaction standards appeared to shield politically exposed individuals without clear legal justification, prompting renewed accusations of selective transparency and covering of elite interests.

Bondi has rejected allegations that the department withheld material for political reasons, insisting that privacy protections for victims and ongoing legal considerations guided the redactions and that the releases were lawful and made in good faith. At a House Judiciary Committee hearing, she faced pointed questions over why the agency had missed statutory deadlines and why the redacted release seemed inconsistent, but often declined to offer detailed justifications for specific decisions. Lawmakers including Democrats and Republicans have expressed frustration at the lack of clarity and accountability in the DOJ’s approach.

Independent legal reviewers and lawyers for Epstein survivors have criticised the structure of the release as deepening distrust rather than clarifying the historical record. Veteran attorneys representing more than 200 alleged victims filed motions asking federal judges to order the takedown of the DOJ’s online Epstein library, arguing that the partial and inconsistent disclosures constituted “the single most egregious violation of victim privacy in one day in United States history.” They contended that error‑riddled redactions undercut survivors’ dignity and obscured rather than illuminated the scope of misconduct.

Survivor advocates and lawmakers have also questioned why significant categories of material remain withheld, including draft indictments, certain FBI interview summaries, and records from earlier federal investigations. Critics argue that the DOJ’s slow pace and heavy blackouts undermine public confidence that prosecutors are pursuing all credible leads against individuals whose names and communications appear in the files.

The gap between publicly known file contents and law enforcement action has fueled broader debate about elite impunity and institutional resistance to accountability. Some observers argue that the pace of release and the continued withholding of many documents reflect structural resistance within the justice system to pursuing cases against powerful figures with extensive political and financial influence. Others contend that federal legal standards and protections for ongoing cases legitimately constrain what prosecutors can disclose and when. The tension between these positions underlines the difficulty of converting documentary exposure into criminal prosecutions in complex transnational networks of influence.

In Europe, the fallout has been pronounced. Former Norwegian prime minister Thorbjørn Jagland lost his parliamentary immunity and now faces investigation for aggravated corruption tied to his ties with Epstein, including alleged gifts and favours that may have occurred during his tenure in high office. Others such as Mona Juul, a former Norwegian ambassador, have resigned and are under investigation alongside her former diplomat husband. In the United Kingdom, former minister Peter Mandelson resigned from the Labour Party and the House of Lords after disclosure of payments and communications with Epstein, and political appointees including chief staff figures stepped down amid growing scrutiny. In France, inquiries opened into former culture minister Jack Lang after documents linked to Epstein surfaced. These developments illustrate that documented relationships with Epstein have consequences in national political arenas beyond the United States.

Despite this global wave of resignations and investigations, the United States has seen a less aggressive legal aftermath. High-profile figures named in the files, including former White House official Kathy Ruemmler and other corporate or political leaders, have stepped down from positions, but criminal prosecutions of named US elites have not emerged publicly on the same scale as in Europe. Legal analysts emphasize that the evidentiary standards for a criminal case. proof of knowledge and participation in criminal activity are distinct from the fact of correspondence or association, and this explains part of the divergence between public outrage and prosecutorial action. Civil litigation continues against institutions and individuals for related harms, and congressional oversight remains active, but the absence of indictments has reinforced perceptions of a two‑tier justice system where wealth and influence insulate the powerful.

Public debate has also invoked broader questions about elite influence during the COVID‑19 pandemic, with litigation in the Netherlands illustrating how reputational and civil accountability can intersect with public health debates. Dutch courts have allowed a civil lawsuit to proceed naming figures such as Bill Gates and Pfizer’s Albert Bourla, alleging harms associated with vaccine communications and information disclosure, even as the underlying legal standard for civil culpability remains distinct from criminal liability. The progression of that case, and debates about access to justice and expert testimony, contribute to a wider narrative about the difficulty of holding globally influential figures to account.

The arrest of Prince Andrew punctures a long-held assumption that hereditary rank and proximity to the Crown provide permanent insulation from criminal investigation. British constitutional historians have argued that the legitimacy of the monarchy and of public institutions more generally depends upon visible subjection to the rule of law in moments of crisis. A charge of misconduct in public office, embedded in statute and tested by evidentiary procedure, exemplifies how legal systems can assert authority over status and rank. It does not satisfy all public expectations about the moral weight of alleged associations, but it establishes a legal foothold upon which further accountability may rest.

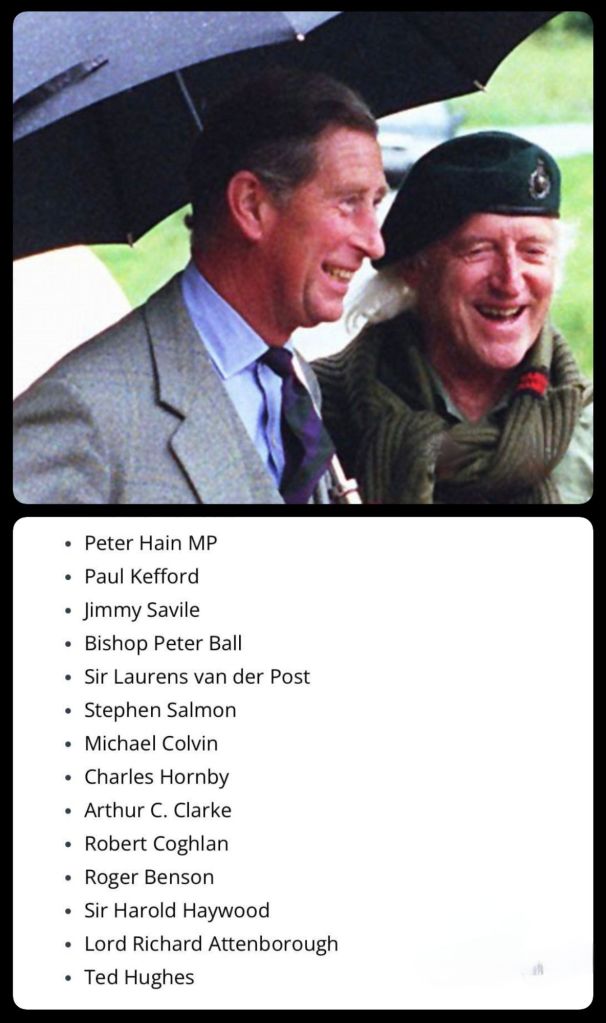

What has shaken public confidence is not only the arrest of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, but the long record of proximity between senior royals and individuals later exposed as abusers or predators. King Charles’s documented correspondence and meetings with Jimmy Savile, later revealed to have been one of Britain’s most prolific sexual abusers, remain a matter of public record. His written support for Peter Ball, who was ultimately convicted of sexual offences, was acknowledged in subsequent institutional reviews. Allegations surrounding Lord Louis Mountbatten have also circulated for years in investigative reporting, though never adjudicated in court. The issue is not retrospective guilt by association; it is whether repeated proximity to individuals later exposed for serious misconduct triggered adequate scrutiny at the time or whether status discouraged it.

The perception of a two-tier justice system emerges from this pattern. Ordinary citizens face swift investigation and prosecution. Yet when the powerful appear in files, correspondence, or testimony linked to Jeffrey Epstein, years pass without visible investigative momentum. Survivors have publicly stated they were never interviewed, even as vast quantities of documents circulate. That disconnect deepens suspicion that accountability operates unevenly when elites are involved.

These questions now extend beyond Andrew as an individual. They reach the institution itself. What did the Royal Household know about Epstein’s access and associations? Were warnings raised internally? Was due diligence performed? If public confidence is to be restored, calls for an independent inquiry into institutional knowledge and oversight cannot simply be dismissed as republican agitation. Transparency is not hostility to the Crown; it is the minimum requirement of constitutional legitimacy.

Historian Dan Snow has warned that the royal family could be heading toward a “terminal crisis” in the wake of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s arrest, stating: “He’s disgraced himself, he’s disgraced the Royal Family, and he’s disgraced our country.” Reform’s Robert Jenrick described the allegations as “very, very serious” and urged the public to “think about the victims” of Epstein. Those remarks reflect a broader shift: the conversation has moved from embarrassment to existential scrutiny.

“Who is behind Jeffrey Epstein? We don’t know exactly who that is.”

“Who told him to set Prince Andrew up?”

A constitutional monarchy survives on consent. Consent depends on the belief that no individual, however titled, however connected, is insulated from investigation. If credible questions continue to meet silence, and if elite networks appear beyond ordinary prosecutorial reach, then debate about structural reform, including the future of the monarchy itself, will no longer sit at the margins. It will move to the centre of political life. At that point, the crisis will not be reputational, but constitutional.

Whether British and American legal systems converge or diverge in their treatment of politically connected figures will be watched closely in coming months. Scholarly consensus across common law jurisdictions affirms that durable legitimacy rests upon impartial enforcement of law rather than symbolic reassurance, and the trajectory of this case, alongside parallel investigations abroad, will test the strength of those principles in practice.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

Thank you for visiting. This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

https://buymeacoffee.com/ggtv |

Leave a comment