The Thai–Cambodian Clashes and the Politics of Managed Chaos in Asia

A Local War with External Hands fuelled by the logic of peripheral destabilisation

Fighting along the Thai–Cambodian border returned in mid-December after a short and unstable pause following clashes earlier in the year. Artillery fire, small arms engagements, and troop movements spread across disputed stretches of the frontier, displacing civilians and forcing both governments to place forces on high alert. The confrontation followed a familiar pattern from earlier border crises but carried wider implications because of timing, geography, and the external environment in which it unfolded.

The Thai–Cambodian border dispute rests on unresolved demarcation inherited from French colonial maps and later bilateral arrangements that never produced a final settlement. Several contested areas hold symbolic value rather than economic worth, yet symbolism has repeatedly translated into violence. Earlier confrontations around the Preah Vihear temple complex demonstrated how domestic politics, military signalling, and nationalist pressure could escalate rapidly. The latest fighting followed the same structural logic, though circumstances surrounding Southeast Asia have changed in ways that make renewed conflict more dangerous.

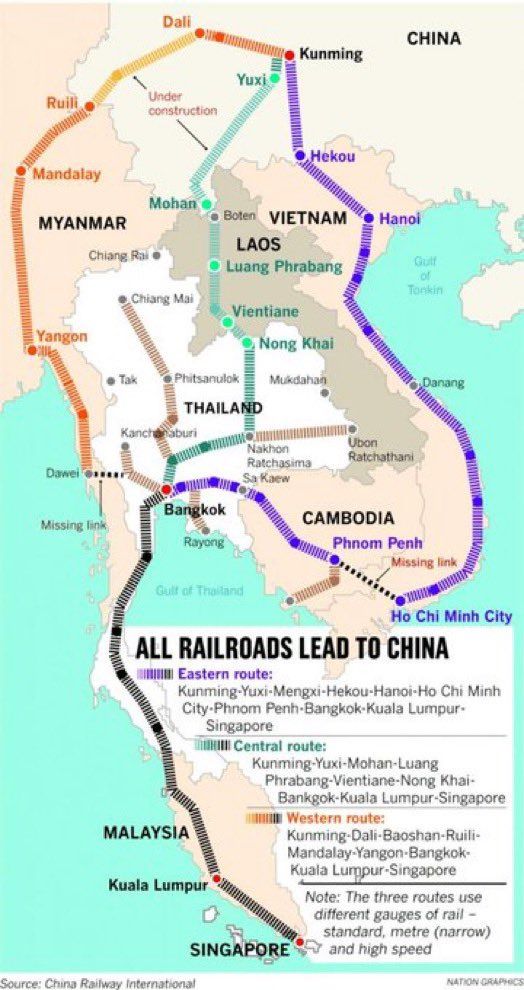

Thailand occupies a central position in mainland Southeast Asia, linking the Indochinese peninsula to maritime routes and acting as a transit corridor for trade, energy, and infrastructure. Cambodia remains economically weaker and more dependent on external partnerships, particularly Chinese investment and development finance. Any prolonged conflict between the two disrupts regional connectivity and introduces instability close to key Chinese transport corridors running through Laos and northern Thailand. Analysts at the Chulalongkorn University Institute of Asian Studies have long noted that mainland Southeast Asia functions as an integrated economic space rather than a set of isolated national markets, meaning even localised fighting produces wider regional effects (Chulalongkorn IAS working paper series, 2022).

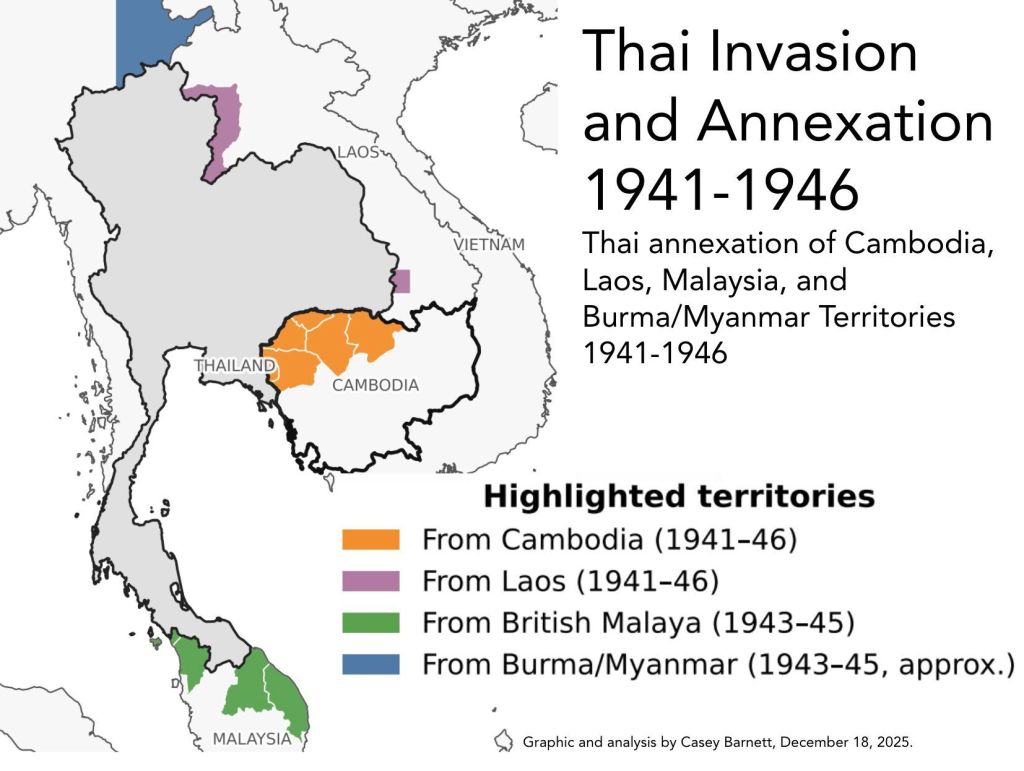

In 1941 Thailand invaded Cambodia after claiming cross-border attacks by colonial forces, later declaring war on the United States and the United Kingdom, a pattern of justification that bears resemblance to present accusations used to legitimise renewed military action. Thai authorities entered into a formal treaty with Imperial Japan in June 1940 despite well-documented Japanese atrocities in China, including the 1937 Nanjing massacre, and this agreement facilitated Japan’s subsequent occupation of French Indochina and British Malaya. Following months of preparation, Thai forces moved into Cambodian and Lao territory in January 1941, rapidly annexing northern Cambodian provinces and western Lao regions under claims of defensive necessity. A further agreement in December 1941 aligned Thailand militarily with Japan and secured Japanese backing for Thai territorial claims across Cambodia, Laos, Malaya, and Burma, positioning Thailand as a logistics base for Japanese campaigns between 1941 and 1942. Japan later transferred additional territories to Thailand in 1943 as compensation for cooperation, while Thailand benefited materially from forced labour used in constructing the Burma Railway, where thousands of Allied prisoners of war died under extreme conditions. After the Allied victory, Thailand was compelled to relinquish all annexed territories, though postwar accountability remained limited after the United States opposed British proposals for punitive occupation on grounds of regional stability. That historical record establishes a precedent in which border incidents, external alliances, and strategic opportunity combined to enable territorial expansion, a pattern now resurfacing amid renewed fighting along the Thai–Cambodian frontier in 2025.

The December escalation followed months of unresolved tension after earlier hostilities in July. That earlier fighting ended without a durable mechanism for de-escalation, leaving forces deployed forward and communication channels thin. Military analysts from the Singapore-based S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies observed that ceasefires along disputed borders without joint monitoring arrangements tend to harden positions rather than soften them, as commanders prepare for renewed clashes rather than withdrawal (RSIS Commentary No. 148/2021). The Thai–Cambodian case fits that pattern closely.

Geography adds another layer of risk. Cambodia borders Laos, which shares a direct frontier with China. Thailand lies only marginally short of the Chinese border and hosts infrastructure linking southern China to ports on the Gulf of Thailand. Any instability along Thailand’s eastern frontier raises concerns in Beijing about supply chains, energy transit, and the security of overland routes developed under the Belt and Road framework. Chinese scholars at Yunnan University have repeatedly described mainland Southeast Asia as China’s strategic rear area, vulnerable to disruption through peripheral conflicts rather than direct confrontation (Yunnan University Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 2020).

External interest in the Thai–Cambodian dispute cannot be separated from broader great power competition. United States policy documents over the past two decades have openly described the use of peripheral pressure to constrain rival powers. Strategic planning papers from the RAND Corporation and earlier US Army War College studies discussed exploiting regional disputes to stretch adversary attention and resources, particularly along Russia’s borders during the post-Cold War expansion of NATO (US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, 2001). Comparable logic now appears in the Indo-Pacific context, where friction around China’s periphery serves wider containment objectives.

Independent analysts have pointed out that Washington’s approach to Southeast Asia increasingly mirrors earlier strategies applied in Eastern Europe. Former Australian diplomat Tony Kevin argued that destabilisation through local conflicts allows external powers to deny rivals a stable regional environment without direct military confrontation, shifting costs onto local states (Kevin, Return to Moscow, 2017). The Thai–Cambodian conflict, though rooted in historical disputes, provides a ready-made pressure point near China’s southern flank.

Cambodia’s foreign policy alignment complicates the picture. Phnom Penh has cultivated close ties with Beijing, receiving infrastructure investment, military assistance, and political backing. Thailand, while maintaining relations with China, remains a formal US treaty ally and hosts joint military exercises with American forces. This asymmetry creates incentives for external actors to encourage friction under the guise of neutrality or mediation. The Lowy Institute has noted that Southeast Asian border disputes often attract disproportionate external attention when they intersect with alliance structures rather than purely local concerns (Lowy Institute Analysis, 2019).

Domestic political factors also played a role in the December escalation. Both governments faced internal pressures that rewarded assertive posturing. In Thailand, military influence within politics remains significant, and border tensions have historically served to reinforce the armed forces’ role as guardians of national sovereignty. Cambodian leadership, meanwhile, has used external threats to rally domestic support and deflect criticism over economic inequality and governance. Political scientist Sophal Ear observed that Cambodian nationalism tends to intensify during periods of internal strain, making border disputes politically useful despite their economic costs (Ear, Aid Dependence in Cambodia, 2012).

Yet domestic explanations alone fail to account for the timing and persistence of the fighting. Regional observers from the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney argued that renewed clashes coincided with heightened US diplomatic activity across Southeast Asia, including security dialogues emphasising resilience against coercion and the need to counter unnamed external influence. Such messaging, even when framed abstractly, signals encouragement for firmer stances rather than compromise (CIS Policy Paper, 2023).

ASEAN’s inability to manage the crisis exposed structural weaknesses within the regional organisation. ASEAN principles of non-interference and consensus decision-making limit its capacity to intervene decisively in bilateral disputes. Past attempts to deploy observers or facilitate binding arbitration met resistance from member states wary of setting precedents. Scholars at the University of Malaya described ASEAN’s conflict management role as reactive rather than preventative, effective only when major powers remain disengaged (UM Asia-Pacific Research Review, 2021). In the Thai–Cambodian case, external interest reduced space for quiet diplomacy.

Economic consequences extended beyond immediate border areas. Trade routes linking Thailand to Vietnam and southern China experienced delays, while insurance premiums for cross-border logistics increased. Regional chambers of commerce warned that even short disruptions undermine confidence in Southeast Asia as a stable manufacturing hub at a time when firms consider relocating supply chains away from China. The irony lies in the fact that instability along China’s southern approaches ultimately discourages diversification and reinforces dependence on established routes rather than creating alternatives.

The conflict also risks normalising militarisation along borders that had gradually opened to trade and tourism. Analysts from the International Institute for Strategic Studies noted that repeated cycles of mobilisation create permanent security dilemmas, where each side interprets defensive measures as offensive preparation (IISS Strategic Dossier, 2020). Such dynamics reduce incentives for long-term settlement and increase the likelihood of miscalculation.

Beneficiaries of regional chaos emerge indirectly rather than openly. Arms suppliers gain from increased defence spending by states seeking to modernise forces after each crisis. External powers gain leverage by positioning themselves as indispensable security partners or mediators. Strategic competitors benefit when regional integration slows and alternative economic blocs struggle to cohere. None of these outcomes serve the interests of Thailand or Cambodia, whose populations bear the costs through displacement, lost income, and heightened insecurity.

Independent Southeast Asian commentators have warned that repeated border crises risk locking the region into a pattern seen elsewhere, where unresolved disputes become tools of external strategy rather than problems to be solved. Malaysian scholar Kua Kia Soong argued that peripheral conflicts often persist precisely because they remain manageable and exploitable, never escalating enough to force resolution yet never settling enough to fade (Kua, Globalisation and Its Discontents Revisited, 2018).

The December fighting therefore represented more than another episode in a long-running dispute. It illustrated how historical grievances, domestic politics, and external strategic interests intersect to produce instability that outlasts any single clash. Southeast Asia’s centrality to Asian economic growth makes such instability disproportionately damaging, especially as great power competition intensifies around the region’s edges.

Without firm bilateral mechanisms insulated from external pressure, the Thai–Cambodian border will remain a fault line rather than a boundary. The pattern observed during the December escalation suggests that future ceasefires will remain temporary unless the broader strategic environment changes. Regional stability depends less on statements of restraint and more on resisting the use of local disputes as instruments of wider geopolitical design.

Any assessment of responsibility must therefore extend beyond Bangkok and Phnom Penh. The structure of incentives surrounding the conflict points toward actors who benefit from distraction, fragmentation, and the slowing of Asian integration. Understanding that reality remains essential for any serious effort to prevent repetition rather than merely managing the aftermath of the next clash.

Long-term stability along the Thai–Cambodian border requires insulating bilateral dispute resolution from great power rivalry and restoring regional mechanisms focused on economic integration rather than security alignment. Without such insulation, local grievances will continue to be amplified by external interests seeking strategic advantage.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

Popular Information is powered by readers who believe that truth still matters. When just a few more people step up to support this work, it means more lies exposed, more corruption uncovered, and more accountability where it’s long overdue.

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment