Military immunity, data governance, and Kenya’s changing sovereignty

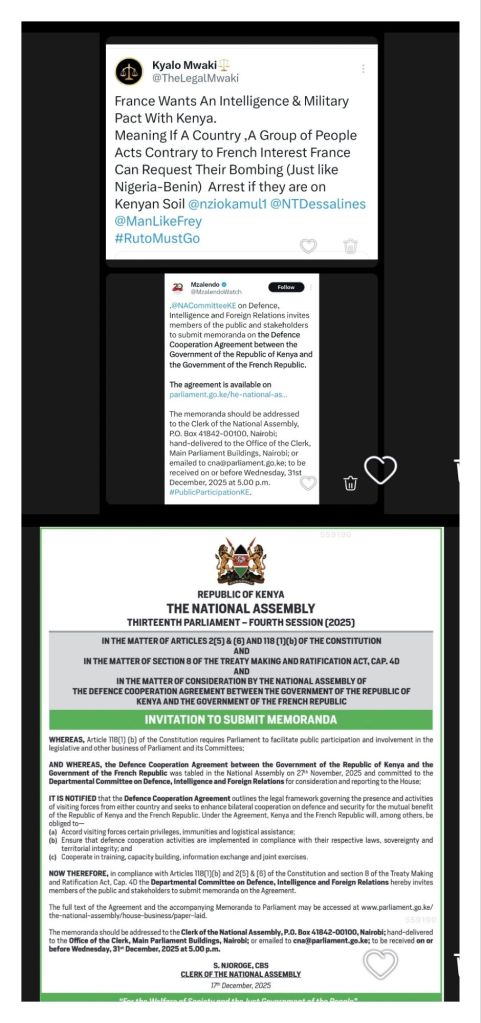

No African leader comes close to President William Ruto when it comes to reversing gains of the liberation struggle and selling their people to western interests for personal gain. If the African people seek an understanding of how the trans-atlantic slavery was facilitated and as a precursor to colonialism, the actions of this president since he came to power are a classic mirror example. Ruto’s administration placed before Parliament a defence cooperation agreement with France during late November, continuing a sequence of Western security arrangements signed since his election. The agreement proposes diplomatic style privileges for French soldiers operating inside Kenya, including legal protections, logistical support, and regulated freedom of movement. Parliamentary committees opened a short window for public submissions, although ratification authority ultimately rests with legislators aligned with the executive.

Kenyan defence officials describe the agreement as a framework for training cooperation, intelligence exchange, and joint military exercises.

French forces would operate under visiting forces provisions similar to arrangements France holds across former colonial territories. Legal immunity clauses restrict Kenyan courts from prosecuting French personnel for actions conducted during official duties. Such clauses carry practical consequences for sovereignty, accountability, and civilian oversight within the host country. Kenyan citizens and institutions would hold limited authority over foreign soldiers operating on domestic territory. Comparable privileges are not extended to Kenyan forces operating inside France. Reciprocity remains absent from the text as publicly described by parliamentary briefings and local reporting. Kenya gains access to training and intelligence channels while conceding jurisdictional authority. France gains operational presence and strategic depth in East Africa.

This military agreement follows earlier Western partnerships signed since Ruto assumed office. Several agreements focused on digital governance platforms, biometric identification systems, and public service databases. American institutions and private contractors feature prominently within these arrangements. Health data agreements granted foreign linked systems access to national medical records infrastructure. Officials argued efficiency gains and funding support justified external involvement. Oversight structures remain weak, with limited public disclosure regarding data storage and secondary usage. Viewed together, military access follows digital and informational access in a clear progression.

Sensitive state functions increasingly depend upon foreign technology, foreign security guarantees, and foreign legal protections.

Domestic capacity building receives less emphasis within official policy statements. Regional context adds further significance to the French agreement.

Across the Sahel, governments expelled French troops after prolonged domestic unrest.

Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger cited sovereignty erosion and political interference concerns. France lost basing access and intelligence reach across large sections of West Africa. East Africa now offers replacement strategic positioning. Kenya provides infrastructure, stability, and diplomatic legitimacy for renewed French military presence. Historical patterns suggest French security partnerships rarely remain limited to technical cooperation. Political influence often follows military dependence.

Examples exist across Francophone Africa where leaders deepened security ties while extending tenure. Kenyan officials deny any linkage between defence cooperation and internal political calculations. Public statements frame the agreement as purely professional and defensiveP Political realities within Africa rarely operate within such narrow boundaries. Immigration policy highlights further imbalance within these relationships.

European states continue tightening entry rules for African citizens.

Africans are classified as migrants or security risks upon arrival. Meanwhile European soldiers receive special legal treatment while stationed on African soil. Language shifts from border enforcement to partnership depending on direction of movement. Such asymmetry reinforces long standing power hierarchies rather than mutual respect.

Kenya also maintains capable military institutions and regional security experience. Peacekeeping operations across Somalia and the Great Lakes region demonstrate operational competence. Dependence on foreign forces therefore reflects political choice rather than absolute necessity.

Industrial development and technology transfer remain marginal within these agreements. Manufacturing investment, research facilities, and skilled employment rarely accompany security deals. Military cooperation substitutes for economic partnership. Parliamentary review represents the final procedural checkpoint. Public submissions may register concern but rarely alter executive direction. Kenya’s foreign alignment increasingly reflects Western strategic priorities. Long term consequences will shape sovereignty, accountability, and regional posture. Future governments will inherit commitments difficult to reverse without diplomatic cost. Such decisions deserve sustained scrutiny grounded in national interest rather than short term convenience.

Western governments have shown consistent effectiveness in shaping puppet leadership outcomes across several African states through finance, diplomacy, security cooperation, and elite networks rather than overt force. Leaders such as William Ruto in Kenya and Bola Tinubu in Nigeria align closely with Western economic and security priorities after taking office. Both administrations expanded cooperation with Western governments shortly after elections, including defence, digital systems, and financial policy alignment. Similar patterns appear in Ivory Coast, Cameroon, and previously Gabon, where leaders maintained power while preserving Western military access and commercial interests. These relationships rely on international legitimacy, debt support, security backing, and diplomatic protection rather than direct control. Elections still occur, but acceptable puppet candidates receive disproportionate external support, favourable media treatment, and rapid post-election recognition. Over time, this produces governments that manage domestic politics while protecting external interests, creating dependence rather than partnership and limiting genuine policy independence.

@Ashleytheebarroness

Authored By : Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment