Kufrah Airstrip in Libya, Bosaso Airport in Somalia, and and Gulf Logistics Sustain the RSF Violent Campaign in Darfur

The war in Sudan has unfolded through familiar scenes of collapse, militia violence, and civilian ruin, yet one of its most decisive engines sits far from the battlefields and beyond public view. A neglected airstrip in southeastern Libya has become a central artery of supply for the Rapid Support Forces, sustaining a campaign of mass killing and forced displacement in Darfur and reshaping the balance of the war. The route linking the Libyan desert, Somalia’s northern coast, and Sudan’s western provinces exposes how external power, logistics, and private military labour now determine the fate of a country undergoing genocide.

The Rapid Support Forces did not emerge as a conventional army. The organisation grew from the Janjaweed militias assembled by Khartoum during the early 2000s to crush rebellion in Darfur. Scholars of Sudanese political violence, including Alex de Waal of Tufts University, have described the Janjaweed as a state-enabled force designed to outsource atrocity while preserving official deniability. The RSF inherited this structure, combining tribal mobilisation, personal loyalty to its commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, and a business model rooted in smuggling, mercenary labour, and resource extraction. When fighting broke out with the Sudanese Armed Forces in April 2023 over control of the state and integration of forces, the RSF entered the conflict with manpower and brutality but without secure industrial supply.

The early phase of the war exposed that weakness. The Sudanese army regained control of Khartoum in March 2024, disrupting RSF supply routes and pushing the conflict’s centre of gravity westward. Darfur once again became the decisive theatre, both for military advantage and for the RSF’s long-standing project of ethnic cleansing. Maintaining an eighteen-month siege of El-Fasher, followed by its capture, required ammunition, fuel, vehicles, trained personnel, and secure rear logistics. None of this could be generated locally at scale.

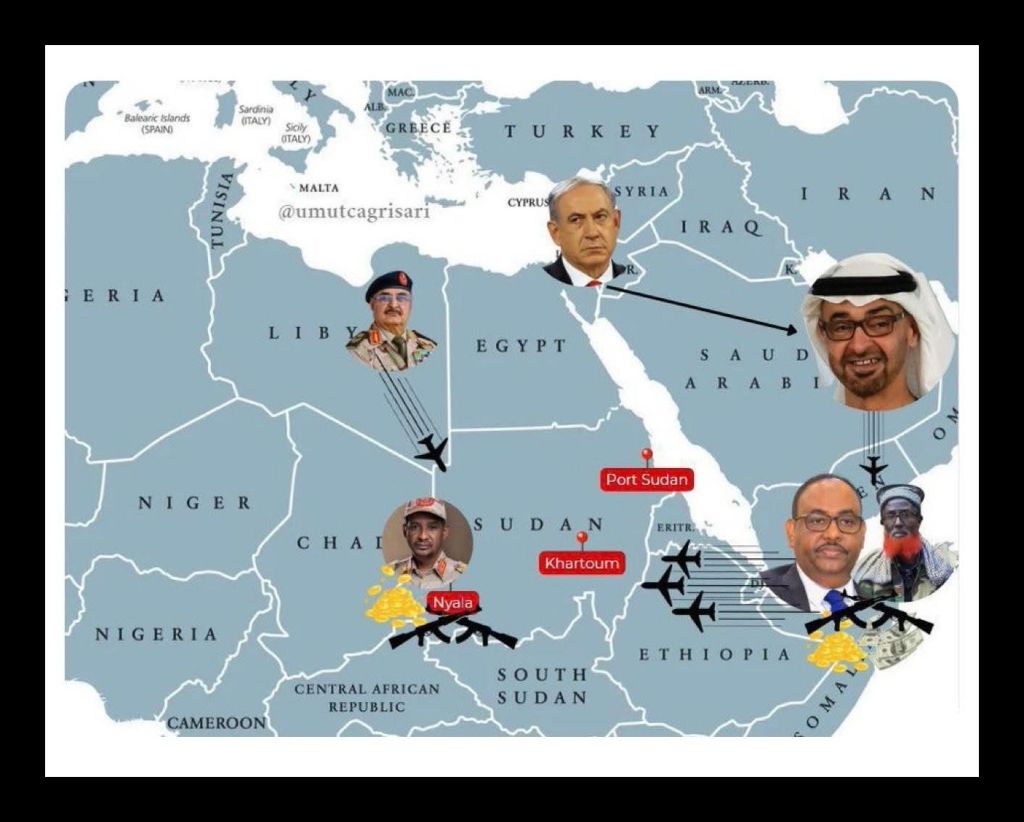

The solution emerged through Libya’s southeast. Kufrah, a remote desert town near the Sudanese border, sits in territory controlled by Libyan armed units aligned with Khalifa Haftar. The area has long functioned as a node in trans-Saharan trafficking networks, moving weapons, migrants, and fuel between the Sahel and the Mediterranean. Research by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime has documented operational ties between Haftar-aligned units and RSF elements well before Sudan’s current war. Those ties provided the human and institutional infrastructure needed to turn Kufrah’s neglected airstrip into a logistics hub.

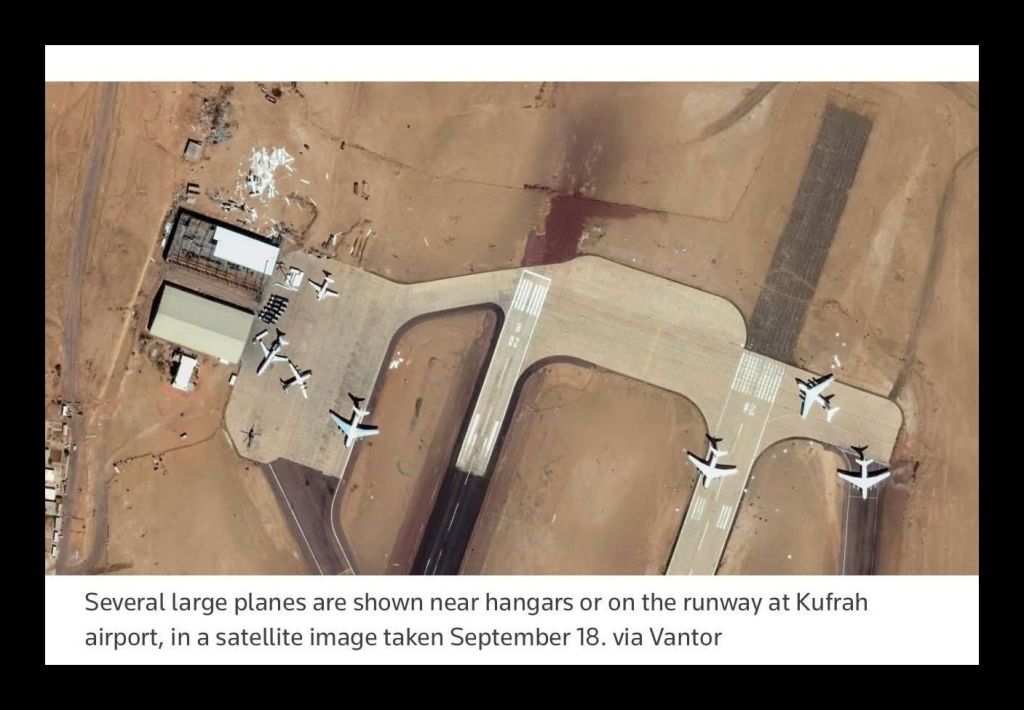

Satellite imagery and flight data analysed by Justin Lynch of the Conflict Insights Group show a sharp increase in heavy cargo traffic beginning in April 2024. Aircraft types, flight origins, and operational patterns matched previous airbridges used to arm Haftar’s forces earlier in the decade. By early summer, the airstrip had undergone visible renovation, including expanded apron space and facilities consistent with sustained military use. The timing coincided with RSF force concentrations forming south of Kufrah, documented by the Centre for Information Resilience through open-source imagery that traced vehicles and fighters moving from Libya into Darfur.

This corridor proved decisive. A senior United Nations official familiar with RSF operations described the Kufrah route as altering the operational environment by allowing uninterrupted resupply during the El-Fasher siege. Military analysts at the Royal United Services Institute have long argued that modern siege warfare depends less on encirclement than on sustaining the attacker’s logistics under international scrutiny. Kufrah provided precisely that insulation. Supplies crossed vast desert distances beyond the reach of Sudanese air power, then flowed directly into RSF-held territory.

The aircraft servicing Kufrah further illuminate the external architecture of the war. Ilyushin-76 cargo planes operated by Kyrgyz-registered carriers previously named in United Nations investigations for weapons transfers to Libyan factions reappeared on the route. These same aircraft had earlier serviced an airstrip in eastern Chad that functioned as an RSF supply line before diplomatic pressure constrained its use. Their redeployment to Libya followed established patterns of sanctions evasion and deniable logistics described by Professor Mark Galeotti of University College London in his work on illicit military supply chains.

Somalia forms the other critical node. Bosaso Airport in Puntland has become a forward logistics base linking Gulf financing, African intermediaries, and Sudanese militias. Puntland’s security sector has received sustained funding and training from the United Arab Emirates for over a decade, a relationship examined in detail by the International Crisis Group. Flights from Bosaso to Kufrah, including aircraft previously used on UAE-linked military routes, demonstrate an integrated supply network rather than isolated transactions.

Personnel flows followed the same channels. An investigation into the recruitment of Colombian ex-soldiers revealed a covert pipeline moving through Abu Dhabi, eastern Libya, and Bosaso before deployment to Darfur. These recruits, drawn by promises of high-paying security work, provided drone operation, artillery training, and tactical instruction to RSF units. Video evidence shows their presence alongside RSF fighters, including children, reinforcing findings by UNICEF and Sudanese civil society groups regarding the militarisation of minors. The outsourcing of specialised violence to foreign veterans aligns with patterns documented by Sean McFate, a former U.S. Army officer and scholar of modern mercenarism, who argues that deniable professional fighters now substitute for state militaries in many conflicts.

The capture of El-Fasher marked the culmination of this system. After months of starvation tactics and isolation, RSF forces entered the city and carried out mass killings of civilians. Independent Sudanese medical networks documented mass graves and execution sites in the aftermath. Darfur researchers at the University of Khartoum, now operating in exile, have noted that the pattern of violence mirrors earlier Janjaweed campaigns but on a broader scale enabled by sustained external supply. Control of Darfur consolidated RSF territorial power and opened new routes into southern Sudan, further entrenching the militia’s position.

Economic motives intersect with strategic ones. The United Arab Emirates has pursued extensive commercial interests in Sudan, including planned investments in agriculture and Red Sea infrastructure. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo’s prior deployment of RSF fighters to Yemen on behalf of Gulf coalitions established personal and financial ties that predate Sudan’s civil war. Analysts at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute have argued that such relationships blur the line between state policy and private military patronage, allowing external actors to shape conflicts while maintaining formal neutrality.

Libya’s role reflects its own fragmentation. Haftar’s forces exercise de facto control over eastern and southern Libya without a unified national command structure. Local commanders operate smuggling networks that serve both economic survival and political leverage. Allowing RSF access to Kufrah fits a pattern of transactional alliances rather than ideological alignment. For Sudanese civilians, the distinction offers no relief.

The result is a war sustained by air corridors invisible to most observers and insulated from conventional diplomatic pressure. Darfur’s destruction no longer depends on local dynamics alone but on a transnational system of logistics, finance, and manpower. Genocide unfolds not as a sudden eruption but as an engineered process maintained by flights, fuel contracts, and permissive airspace.

Breaking this system requires confronting the infrastructure rather than the rhetoric surrounding it. Targeted monitoring of desert airstrips, sanctions enforcement against repeat carrier networks, and exposure of mercenary recruitment pipelines would address the mechanics of violence rather than its symptoms. Without such measures, the RSF’s campaign in Darfur will continue to be supplied from the sky, and Sudan’s mass graves will remain linked to distant runways few citizens ever see.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a reply to swimming49175c102e Cancel reply