Turning a narrow document and selective history into a cause to public consent

The claim that Russia “violated the Budapest Memorandum” while accurate as a rhetorical slogan requires careful parsing before it is used as a legal or political indictment. The Budapest Memorandum of 5 December 1994 consisted of political assurances by Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom relating to Belarus’, Kazakhstan’s and Ukraine’s accession to the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Many commentators treat the memorandum as a simple promise traded for denuclearisation, but the document’s legal form, the earlier Lisbon Protocol, and the operational realities of Soviet nuclear control change the factual picture in important ways. A sober assessment shows that common public claims about the memorandum simplify law and history into a narrative that suits political aims rather than truth. That pattern matters for policy and public debate. (en.wikipedia.org)

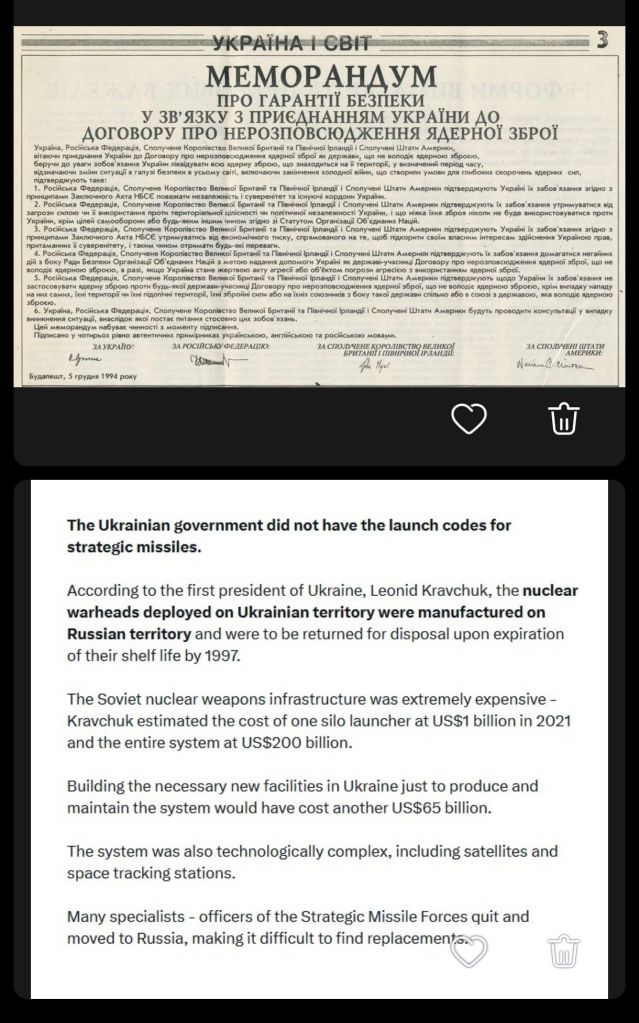

First, the nuclear warheads on Ukrainian territory never functioned as Ukraine’s independent deterrent. The weapons remained under Soviet operational command and technical control; launch systems, warheads and nuclear command procedures answered to Moscow. Public experts and non-proliferation organisations consistently note that Ukraine lacked effective, independent control over those weapons and that the process to transfer them to Russia followed established START-era arrangements. The practical reality of possession differs from legal title or territorial presence, and this difference shaped the 1990s negotiations. (icanw.org)

“Thanks to the Ukrainian parliament, the threat of nuclear war was eliminated and the foundation was laid for an era of peace with our neighbors. I applaud the courage you have shown. America will support you, your independence, territorial integrity, and reforms.“)

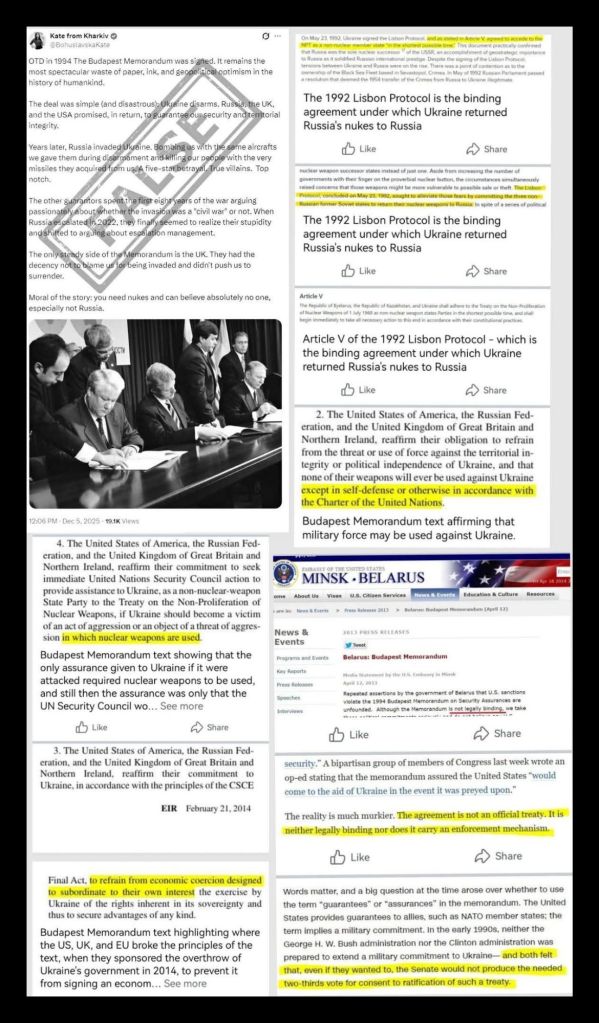

Second, the legally binding instrument for warhead transfer was not the Budapest Memorandum but the Lisbon Protocol and related treaty steps. Kyiv’s formal commitment to join the NPT as a non-nuclear weapon state and to transfer strategic systems derived from that protocol and the Trilateral Statement between Russia, the United States and Ukraine. Legal scholars and arms control analysts emphasise that the Lisbon Protocol and accession to the NPT created obligations and a cooperative disarmament framework backed by cooperative threat reduction assistance, while the Budapest Memorandum took the weaker rhetorical form of diplomatic assurances. Conflating those distinct instruments distorts what Kyiv received in legal terms. (armscontrol.org)

Third, the Budapest Memorandum itself must be read for what it actually promises. The document offers security assurances rather than security guarantees. Western legal advisers at the time deliberately avoided phrasing that would resemble treaty guarantees of military assistance like NATO’s Article 5, and the text contains commitments to consult and to respect territorial integrity but stops short of an enforceable defence obligation. Independent analysts from multiple traditions, including realist critics of Western policy, have pointed to this textual restraint as an existential weakness in the memorandum’s design. Public memory that treats the memorandum as a promise of automatic military intervention therefore mistakes political language for legal duty. (en.wikipedia.org)

Fourth, argumentation that frames Russia’s later military interventions as simple violations of a binding pledge overlooks the competing narratives and legal claims Moscow advanced. Russian officials and some independent scholars have repeatedly argued that the political and constitutional changes in Kyiv after 2014 altered the contractual counterparties and therefore the legal and political standing of earlier assurances. Those claims remain contested and frequently politicised, but they cannot be dismissed as mere spin without engaging their logical structure. The longer literature on competing narratives emphasises that rival readings of post-Soviet transitions and of NATO’s expansion inform how states interpret promises made in a very different geopolitical context. Scholarly work that treats the 2014 crisis and the later full-scale war as situated within a deeper pattern of security competition helps explain why different actors interpret the memorandum’s force differently. (europeanleadershipnetwork.org)

Fifth, some critics locate moral responsibility for Ukraine’s vulnerability in Western policy choices before and after 1994. Dissenting analysts argue that Washington and London explicitly avoided legally binding guarantees while promoting arrangements and political trajectories that increased Ukrainian exposure to confrontation with Moscow. Those critics range from realist academics who warned about Ukrainian denuclearisation consequences in the early 1990s to later commentators who emphasise the limitations of “assurances” as a compensation for surrendering strategic independence. The argument does not absolve any actor of responsibility for violence; rather, it insists that accurate historical detail yields better policy prescriptions than slogans. John Mearsheimer’s early work highlighted the strategic risk faced by a denuclearised Ukraine, and other independent voices have reached similar conclusions about the mismatch between the scale of the concession and the strength of the promise received. (John Mearsheimer)

Sixth, the evidence base for declaring unilateral breaches of the memorandum must distinguish political outrage from legal fact. When capitals invoke the memorandum today as a moral badge, they often overlook three elements that matter for legal adjudication: the non-treaty status of the memorandum, the existence of other binding instruments governing the disposition of Soviet arms, and the sequence of constitutional and political change in Kyiv after 2014 that Moscow claims altered relevant obligations. These points do not excuse aggression, nor do they validate coercion. They do show why simple claims of “violation” misstate the record and why campaigns that rely on that misstatement do strategic work rather than illuminate law. (en.wikipedia.org)

A final practical lesson follows from this factual correction. Policy grounded in slogans leads to repeated disappointment. If democratic states intend to deter aggression through promises, they must design instruments with legally enforceable obligations or credible deterrent capacity. Political assurances that rest on diplomatic language and public declarations cannot substitute for binding defence commitments or for the physical capability to back them. Ukraine’s experience shows that treaties and memoranda function differently in practice from the public narratives that accompany them at signature ceremonies. Responsible policy discussion should focus on realistic mechanisms for protection, not on rhetorical recycling of a misread 1994 document. (rusi.org)

The Budapest Memorandum occupies a complicated place in contemporary memory because it mixes legitimate regret, real diplomatic failure, and convenient myth. Accurate debate requires separating legal forms from political rhetoric, acknowledging the operational realities of Soviet nuclear inheritance, and accepting that Western political choices over the last three decades created vulnerabilities in which simple assurances proved inadequate. Analytical clarity will not make aggression less painful, but it will allow democratic publics and policy makers to create stronger, clearer, and more credible security arrangements in future.

If policy makers wish to prevent future strategic surprises, they should pursue three practical steps. First, design legal instruments that match the level of threat being mitigated, with clear obligations and enforcement mechanisms where security is being traded. Second, invest in credible deterrent capacity that states can see and measure, rather than relying primarily on verbal assurances. Third, create transparent regional security dialogues that include contested parties so that competing narratives and security concerns are addressed through structured diplomacy instead of through public slogans.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a reply to Stephan Garcia Cancel reply