Institutional Self-Displacement at the United Nations: The Board of Peace as a Precedent for the Marginalisation of International Law and the Erosion of Collective Security

The establishment of the Board of Peace represents a decisive institutional rupture in the post-1945 international order, because its legal form and political authority directly supersede the foundational role of the United Nations Security Council. The formal approval of this body by the Security Council, coupled with the appointment of a single national executive as its effective owner and chair, altered the relationship between multilateral governance and sovereign power. Yanis Varoufakis has argued that this decision constituted an act of institutional self-abolition, because the United Nations voluntarily delegated its core mandate for peace and security to an externalised mechanism lacking universal accountability. The implications of this act extend beyond procedural innovation, because they redefine how international legality is constituted and enforced.

The United Nations Charter assigns responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security to a collective body operating through agreed legal constraints. Scholars of international law such as Hersch Lauterpacht emphasised that the authority of the United Nations derived not from coercive supremacy but from procedural legitimacy grounded in universal participation. The Board of Peace departed from this logic by centralising decisive authority within an executive structure detached from the Charter’s normative framework. Varoufakis’s analysis situates this development as a qualitative break rather than an incremental erosion, because the United Nations no longer mediated power but instead ratified its displacement.

The Security Council’s endorsement of the Board of Peace signalled a departure from its historical function as an arena of constrained rivalry among great powers. Martin Wight’s realist interpretation of international society acknowledged power asymmetry while maintaining that institutional forms imposed limits on unilateral domination. The Board of Peace removed these limits by formalising discretionary authority without reciprocal obligations. Varoufakis’s contention that historians will identify this moment as the effective end of the United Nations reflects the view that institutions lose meaning when their foundational purposes are surrendered by their own governing bodies.

The abstention of China and Russia, rather than outright opposition, revealed the depth of institutional decay already present within the system. Varoufakis expressed frustration with this abstention, yet acknowledged that the reasoning advanced by both states reflected a recognition of irreversible structural change. International relations theorist Hedley Bull argued that institutions survive only when they reflect shared expectations about restraint and legitimacy. The abstentions indicated that key actors no longer regarded the United Nations as capable of fulfilling this role, and therefore declined to legitimise the process while also declining to prevent it.

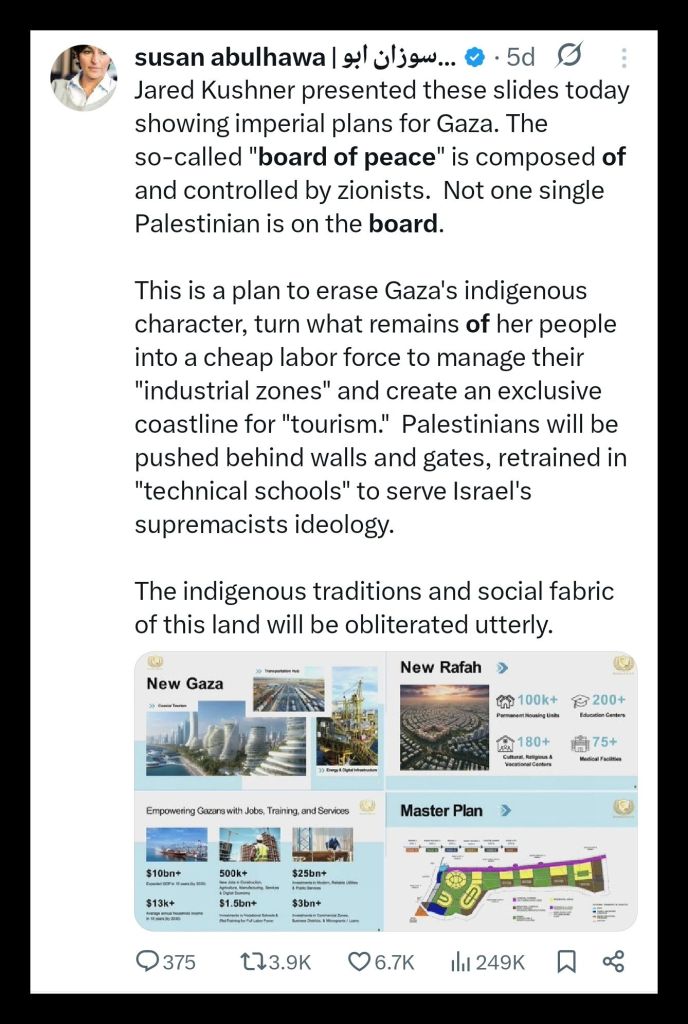

The Board of Peace also represented an implicit acknowledgment that longstanding conflicts previously managed through international law had been removed from legal time altogether. Varoufakis characterised this shift as an end of history specific to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, rather than an ideological endpoint in the sense articulated by Francis Fukuyama. The United Nations had accumulated decades of resolutions, monitoring mechanisms, and diplomatic precedents addressing this conflict, forming what Varoufakis described as an institutional memory rather than a tactical apparatus. This memory embodied legal continuity, even when enforcement proved elusive.

By transferring authority to a new body unencumbered by this institutional memory, the Security Council effectively erased the accumulated legal record governing the conflict. Legal scholars such as Antonio Cassese have argued that repetition and consistency are central to the formation of customary international law. The Board of Peace bypassed this process by privileging executive discretion over legal continuity. Varoufakis’s analysis implies that the conflict was no longer subject to historical adjudication, but instead frozen into a permanent administrative outcome defined by power rather than law.

The erosion of international law inherent in this shift cannot be separated from the broader transformation of global governance. The United Nations system was designed to function through procedural delay, negotiated compromise, and normative accumulation. Political theorist Hannah Arendt observed that such procedures restrain violence by embedding action within shared processes rather than decisive acts. The Board of Peace reversed this logic by valorising speed, finality, and executive clarity at the expense of deliberation. Varoufakis interpreted this as an abandonment of law in favour of managerial resolution.

This transformation also altered the meaning of legitimacy within international relations. Traditionally, legitimacy emerged from adherence to agreed rules rather than from outcomes alone. Jürgen Habermas argued that legitimacy in complex systems depends on procedural justification rather than instrumental success. The Board of Peace substituted procedural legitimacy with outcome-based authority, implying that peace, however defined, justified the suspension of legal norms. Varoufakis rejected this substitution, because it eliminated the distinction between lawful peace and imposed order.

The precedent established by the Board of Peace extends beyond any single conflict or institutional arrangement. By demonstrating that the Security Council could transfer its authority wholesale without constitutional revision, the decision undermined the permanence of all United Nations mandates. Legal historian Martti Koskenniemi has written that international law depends on the belief that rules endure beyond political convenience. The Board of Peace contradicted this belief by revealing that foundational structures could be dissolved through ordinary resolutions. Varoufakis’s assessment therefore situates the decision as a systemic event rather than a policy anomaly.

The practical irrelevance of the United Nations following this decision arises not from formal dissolution but from functional redundancy. Institutions persist only when they perform indispensable roles within political systems. The Board of Peace assumed the decisive role previously reserved for the Security Council, leaving the United Nations with symbolic functions disconnected from power. Varoufakis’s argument aligns with sociological institutionalism, which holds that organisations lose authority when their roles become ceremonial rather than operative. The continued existence of the United Nations under these conditions reflects inertia rather than relevance.

International law similarly entered a phase of managed suspension rather than explicit repeal. By approving the Board of Peace, the Security Council signalled that legal norms could be selectively bypassed without formal violation. This dynamic resembles what Giorgio Agamben described as a permanent state of exception, where legal order persists in name while executive discretion governs practice. Varoufakis’s critique highlights that such arrangements hollow out law from within, rendering legal language incapable of constraining power.

The long-term consequences of this development extend to future conflicts and institutional arrangements. Once precedent establishes that multilateral authority can be reassigned to executive bodies without universal consent, the principle of sovereign equality loses operational meaning. Scholars such as Anne-Marie Slaughter have emphasised that networked governance relies on mutual recognition of authority rather than hierarchical command. The Board of Peace replaced networked legitimacy with hierarchical delegation, altering the grammar of international cooperation.

The decision therefore marks a transition from a rule-based international order to a discretionary management system justified by pragmatic outcomes. Varoufakis’s analysis does not present this transition as accidental, but as the culmination of decades of institutional weakening and selective enforcement. The Board of Peace crystallised these trends into a formal structure, making explicit what had previously operated through informal practices. The United Nations, by endorsing this structure, acknowledged its own obsolescence as a legal guardian.

The importance of this moment comes from the fact that it brings an existing process to a definitive end rather than introducing something entirely new. International law has survived numerous violations, yet it depended upon the continued assertion of its authority by its own institutions. The Board of Peace represented a conscious decision to relinquish that authority. Varoufakis’s assessment therefore frames the event as an endpoint, where the language of international law remains available but no longer governs outcomes. In this sense, the irrelevance of the United Nations emerges not from external assault but from internal abdication.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support.

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

Leave a reply to richardgajics Cancel reply