How policies that killed millions in British India were rebuilt into global institutions and follow the same rule: markets before human survival

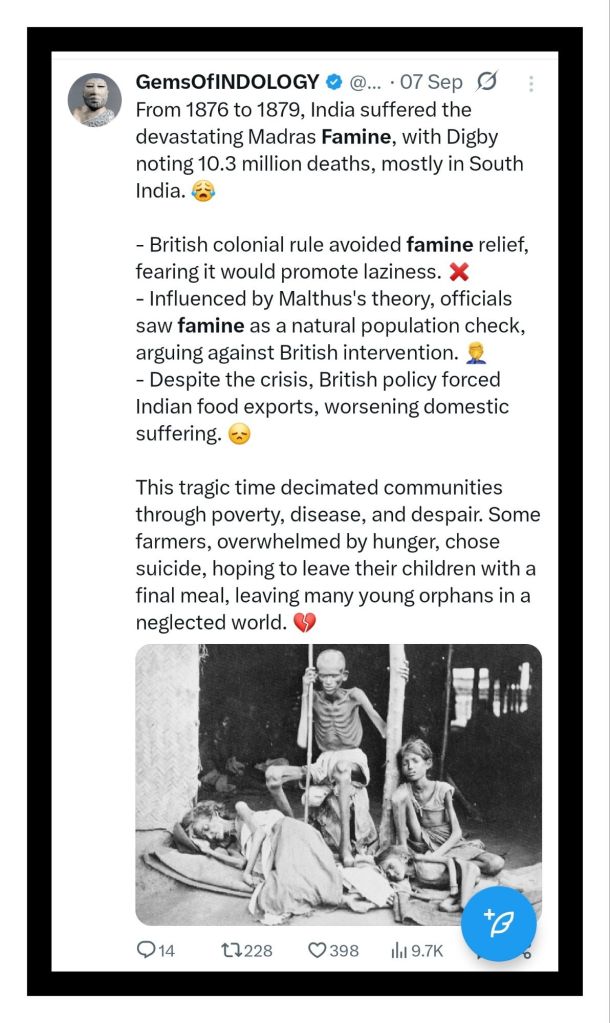

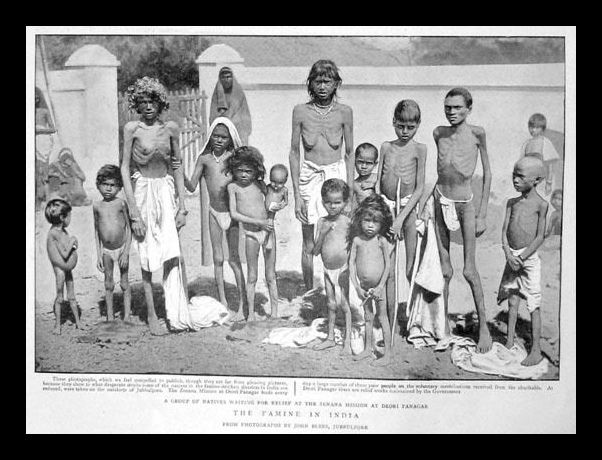

Millions died in South Asia during the Great Indian Famine of 1876–1878 because officials managing the British Empire believed that famine served a market function. Agrarian society collapsed under drought but produce still moved out of ports to London warehouses. People starved while grain traders enjoyed windfall profits. The state enforced cash taxes even as peasants lost income and food supply at the same time. Bureaucrats insisted that price controls, food imports, or relief might distort the operation of free trade. Elites accepted the death of an entire class of the poor as an unavoidable cleansing of the labour market. The scale of death cannot be separated from the ideology governing it.

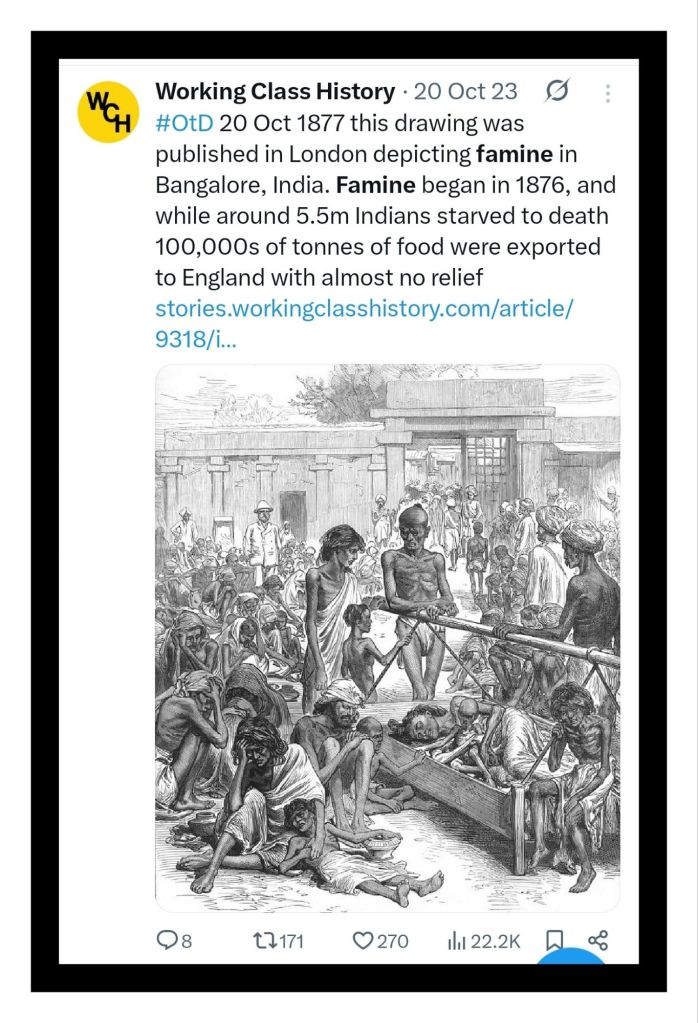

The famine stretched across Madras, Bombay, and Mysore presidencies. Contemporary observers recorded images of entire families dying on the roads while boats full of grain left for foreign buyers. The number of dead is estimated between five and ten million. The colonial government denied responsibility and blamed climate. Administrators in London declared that intervention would breed dependency among the colonised. These views aligned with the prevailing school of liberal political economy in Britain. Free market doctrines of the period treated hunger as a sign of inefficiency, not of injustice.

Lord Lytton served as Viceroy during the crisis. Grain exports from India rose rather than fell. Land revenue collection continued without adjustment. Villagers sold seed stock in order to meet taxes, and fields lost the ability to recover. Reports from the time describe armed police escorting grain carts to ports while the local population watched in silence from famine camps. British journalist William Digby warned that government policy turned drought into disaster, a warning ignored until the scale of death became too large to hide. Digby called the government record “a hideous story of human suffering maintained in the name of political economy”.¹

Relief camps, when opened, were designed around deterrence. Rations fell below the caloric needs of a convict in a Victorian jail. The official handbook for famine camps instructed managers to minimise generosity so that workers would return home at the earliest opportunity. Many did not survive long enough to leave. Historian Mike Davis described these programs as screens for forced labour on public works.² Government officials argued that large public feeding programmes would slow adjustment of the market and reward the unproductive. Large landowners continued exporting surplus grain at global prices, shielded by colonial force. Drought did not build the graveyards. The economic system did.

Charles Trevelyan, architect of earlier famine policy in Ireland, became a model for India. Trevelyan insisted during the 1840s that famine should “correct” what he called the excessive survival of those dependent on the state. Private charity was discouraged as sentimental interference. The same thinking held power in India thirty years later. Trevelyan embraced mass starvation as evidence of divine discipline, and this reasoning merged into official policy that defended London’s economic structure.³ The empire wrote death into the budget line.

The framework that guided India became a reference point for institutions that develop global economic governance today. The belief that crisis should discipline populations, that the poor must suffer in order for markets to function, and that the state must enforce austerity even in catastrophe runs through the modern international architecture. The language changed, the objective remained. The International Monetary Fund inherited the role of enforcing adjustment on weak nations. Programmes tied to loans function like the revenue demands of colonial rule. Relief is conditional. Domestic protection of food and fuel supply must be removed before any funds arrive.

Argentina experienced this shift most brutally in 2001. The IMF demanded deep cuts to pensions, social spending, and wages. Public assets moved into private hands at fire sale values. GDP collapsed by eleven percent in a single year. Poverty surged from under thirty percent to over half the population. People looted supermarkets because they had no other choice. Fourteen million Argentines fell below the poverty line within months. The IMF congratulated the government for what it described as courageous reforms.⁴ Many Argentines saw the policies as a foreign power enforcing failure for the benefit of creditors.

Zambia became a showcase for structural adjustment in Africa. Once a food-secure state producing its own maize, the government was ordered to remove subsidies and expose farmers to foreign commodity markets. Food prices tripled overnight. Riots spread through the cities. A country capable of feeding itself became dependent on imports and aid. Foreign agribusiness firms increased profit through export control and market access. Rural families moved into unstable wage labour arrangements, mirroring the experience of Indian peasants during the colonial export boom.⁵ Hunger followed the ideology more reliably than weather patterns ever did.

India itself did not escape in the modern era. A 1991 bailout forced the government to devalue its currency, reduce food storage, and open agriculture to foreign inputs. Imported patented seeds replaced local varieties. Farmers produced high-value exports for global buyers while their own households faced malnutrition. Hundreds of thousands of farmers killed themselves over debt built into the new system.⁶ Debt collection agencies seized land with the blessing of the modern state. The logic connecting this outcome to the nineteenth century rests on a single claim: the state must assist financial institutions and not protect smallholders from coercive markets.

Pakistan saw the pattern again in 2022. Devastating floods displaced tens of millions. The IMF halted new lending until fuel subsidies were cut. Domestic energy prices exploded. Families already living in tents faced bills they had no capacity to pay. International officials delivered praise for reform while citizens waited for food deliveries that did not arrive in time. The message to the poor did not differ from that given to starving communities under Lytton. Sacrifice was required to maintain confidence in the market.⁷

These policies hold legitimacy among global technocrats because they serve investors. The public face describes the adjustment process as rational, objective, and scientifically planned. The results show violence through economic pressure. As US political scientist Mark Blyth argues, austerity shifts the burden of financial mistakes from capital holders to households.⁸ Hunger becomes a policy tool rather than an accident. When international creditors demand commodity exports to service debt, the food supply of the population becomes vulnerable to external shocks. The poor are expected to absorb the cost so that bondholders remain safe.

Economic historian Utsa Patnaik studied British records and found that colonial taxation extracted wealth equal to trillions in current dollars from India.⁹ Extraction relied on policies that forced Indians to sell to the Empire at low prices, then buy imported goods at high ones. The famine years exposed the cruelty of the system. Administrators believed that grain should flow out regardless of domestic suffering. India’s exports supported British consumption. London denied responsibility because markets functioned as designed. The famine became evidence of discipline, not of failure.

The modern version uses financial contracts rather than armed force. The IMF denies responsibility when poverty increases after adjustment, claiming that countries must endure hardship before recovery. Critics argue that the hardship is not temporary or accidental. The same justification that Trevelyan used to defend food exports from Ireland during the potato blight reappears in World Bank papers describing the benefits of liberalising agriculture. The language is abstract. The effect is starvation.

Naomi Klein’s work on disaster capitalism describes a consistent structure.¹⁰ Crisis events create openings for reforms that are politically impossible in calm periods. The reforms remove protections, privatise resources, and generate dependence. The ideology behind these changes assumes that populations will adapt or perish. This mirrors the Victorian belief that nature punished those who did not compete successfully for work. Both frameworks use the same assumptions about human life and economic necessity.

In the nineteenth century, administrators like Lytton claimed to obey natural laws of supply and demand. The next century replaced those laws with modelling software and growth projections. The moral claim did not change. Governments must not protect the poor from market pressure. Famines provide discipline and remove what officials call excess population. Adjustment programmes provide discipline and suppress what officials call fiscal irresponsibility. The names differ. The deaths remain real.

Research by Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang shows that countries once forced to liberalise agriculture through loan conditions later faced dependency on foreign food and input suppliers.¹¹ Farmers bore the costs of price volatility. Governments lost power to intervene. Modern famines in places like Ethiopia and South Sudan show that hunger spreads fastest where countries lose sovereignty over grain production and distribution.

Leadership within the IMF claims that free markets cure poverty. Evidence from decades of adjustment contradicts the claim. When Zambia lost control of maize production, hunger increased. When Argentina cut social protection, working families fell into destitution. When Pakistan raised fuel prices in floods, communities already displaced sank deeper into crisis. The economic doctrine used to justify each of these outcomes resembles the doctrine that treated Indian peasants as disposable. The order of priority always protects foreign investors first.

Critics argue that global finance requires scarcity and wage desperation to keep food prices low. When wages rise in poorer countries, exporting agribusiness loses competitiveness. Adjustment policies undermine labour bargaining power, which reduces the price of work and, by extension, food. The policy does not serve farmers. The policy serves the companies purchasing their crops. In nineteenth-century India, the same drivers operated. Cash taxation forced peasants to sell cheap. Export merchants sold high. The state ensured the system kept running even as bodies filled the roads.

British Member of Parliament Charles Bradlaugh condemned famine administration during a debate in 1878. He accused the government of sacrificing human beings to theory.¹² Contemporary critics say the IMF repeats this sacrifice when it forces countries into cuts that break food distribution. Countries are told that any effort to subsidise staples counts as market distortion. Distortion for whom becomes the question. Investors overseas cannot tolerate a country feeding its poor at the expense of external creditors. Adjustment restores the correct hierarchy.

If the purpose of an economy is to keep people alive, then the free market answer fails in famine conditions. If the purpose of an economy is to preserve the financial claims of elites, famine becomes a method. The British Empire acted upon the latter belief. The IMF institutionalised it across the world.

The famine in India did not represent accidental mismanagement but reflected a deliberate theory. Policy documents show clear lines of thought. Government memoranda warned against supplying low-cost grain to the starving. Lytton demanded that relief follow strict limits to avoid creating what officials called laziness. Merchants petitioned that controls must not block their trade. Agriculture remained structured around export supply chains even when local hunger grew. The line between famine and famine-inducing policy blurred.

In the contemporary world, policy reports from the IMF promote fiscal consolidation during recession. When low-income countries request room to protect staples and subsidise energy, they are told to prioritise debt servicing. These conditions match the colonial posture: extract value from peripheral territories and treat localhumanity as a lower priority. The result in India was famine. The result across Africa and Latin America has been mass hunger. In both eras decision-makers accepted that a portion of the population could disappear without consequence to policy.

“In 2020, [the World Economic Forum] enacted a 10-year transition to a global, authoritarian political system called stakeholder capitalism.”

“One of their agendas, by 2030, is to own the food supply chain.“)

Historians have argued that Britain did not intend genocide in India on premise that intention does not alter the death count. Officials responsible for millions of deaths believed famine served a higher purpose. The intent is visible in the refusal to suspend exports and the punishment of relief. Economic theory became an alibi for extermination through starvation. Modern institutions using the same theory cannot escape the same charge when their policies cause widespread death. The system treats deprivation as natural selection.

After the famine, the Empire continued using free market thinking as a tool of discipline. Nations dependent on trade did not challenge Britain’s position. Today, debtor countries following adjustment plans do not challenge international finance. Elites in the centre benefit from scarcity in the periphery. The structure creates stability for capital and instability for labour. The famine taught colonial elites that death would not threaten their power. The IMF learned the same lesson during every adjustment crisis where hunger rose yet the programme continued without modification.

The record shows that hunger follows policy choices. Markets do not feed the powerless. Drought and flood become total disasters only when authorities choose to sacrifice the many for the stability of the few. The Great Indian Famine demonstrated that free market ideology became deadlier than any weather event. Structural adjustment revived the method under new branding. Starvation functions as a regulatory tool in a system that rewards hoarding, penalises self-sufficiency, and refuses protection to the vulnerable.

The end of colonial rule did not end extraction. The administrative language changed. The purpose did not. Peasants in India lost seed stock to British tax collectors. Farmers in Africa lose land to agribusiness creditors. Jobless workers in Argentina lost pensions to IMF reforms. Flood victims in Pakistan lost subsidies while international lenders approved the policy. Each policy acted with indifference to local life and dedication to global capital.

The Great Indian Famine exposed the belief that markets come before people. Structural adjustment proved that this belief survived independence. The scale of suffering marks globalist economics as a machinery that trades human lives for financial efficiency. Governments influenced by these institutions continue to treat starvation as collateral. The ideology in its purest form views death as a necessary process of adjustment.

After the famine, the Empire continued using free market thinking as a tool of discipline. Nations dependent on trade did not challenge Britain’s position. Today, debtor countries following adjustment plans do not challenge international finance. Elites in the centre benefit from scarcity in the periphery. The structure creates stability for capital and instability for labour. The famine taught colonial elites that death would not threaten their power. The IMF learned the same lesson during every adjustment crisis where hunger rose yet the programme continued without modification.

We are now witnessing analogous pressures under contemporary global governance initiatives. Policies derived from the UN’s Agenda 21 and Agenda 2030, alongside programmes promoted by the World Economic Forum (WEF), frame climate mitigation and sustainability as imperative while reshaping agriculture, livestock, and food systems. Critics argue that these measures, although couched as progressive or environmentally necessary, often disrupt traditional farming practices, reduce local food autonomy, and weaken resilience across supply chains.¹³ Efforts to limit livestock production, regulate land use, or introduce novel feed additives such as Bovaer have unintended consequences for protein supply and dairy production. Weather-engineering programs and climate interventions, including cloud-seeding and other atmospheric manipulations, carry unpredictable effects on rainfall and soil fertility, potentially intensifying droughts or floods that threaten crop yields. The expansion of genetically modified seeds, agricultural vaccines, and reliance on corporate-controlled agrochemicals creates dependency and undermines biodiversity, while the decline of pollinators further compromises crop reproduction. Extreme weather events, compounded by regulatory pressure, soil degradation, and fragile global supply chains, converge to produce a system vulnerable to shortages and localized famine.¹⁴

These developments echo the structural logic that drove the Great Indian Famine. In both historical and modern cases, policy prioritizes external market interests over local food security, and human survival is treated as secondary to the efficient operation of economic or governance systems. Colonial administrators extracted grain and imposed cash taxes, while modern institutions impose conditions, standards, and regulatory frameworks that reduce farmer autonomy and control over production. The tools have changed, but the outcome, vulnerability and risk to ordinary populations, persists.

Efforts to reshape food production under these global frameworks risk reproducing the logic of past famines unless human survival becomes the central metric of policy success. Structural adjustment in the late twentieth century demonstrated that subordinating local needs to market efficiency amplifies food insecurity. Today, the combination of environmental targets, supply chain centralization, and technological dependency creates conditions in which even minor shocks can propagate into broader food crises. The continuity is unmistakable: elite priorities and external enforcement consistently outweigh local resilience.

Economic systems reflect choices. The Empire made choices that killed millions in India. International institutions make choices that increase the vulnerability of populations to hunger and scarcity. These choices do not follow a natural law. People write the rules. People enforce them. People can change them. The victims of policy do not disappear. They leave records of a world designed to sacrifice them. The belief that markets, or external governance frameworks, should dominate human survival created the famine and continues to threaten global populations today.

Authored By: Global Geopolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

https://ko-fi.com/globalgeopolitics

Endnotes

- William Digby, Prosperous British India (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901).

- Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001).

- Cited discussion in Peter Gray, The Irish Famine (London: Thames & Hudson, 1995).

- Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents (London: Allen Lane, 2002).

- John Loxley, Debt and Disorder: External Financing for Development (London: Zed Books, 1998).

- P. Sainath, Everybody Loves a Good Drought (New Delhi: Penguin, 1996).

- Analysis by Pakistani economist Qaiser Bengali, Karachi Policy Insights, 2023.

- Mark Blyth, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea (Oxford: OUP, 2013).

- Utsa Patnaik, “Revisiting the drain, or transfer from India to Britain in the context of global diffusion of capitalism,” Global Dialogue, 2017.

- Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine (London: Penguin, 2007).

- Ha-Joon Chang, Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2007).

- Hansard Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, Session 1878.

- Vandana Shiva, Oneness vs. the 1%: Shattering Illusions, Seeding Freedom (Penguin India, 2019).

- IPES-Food, “A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems in a Time of Crisis,” 2021.

Leave a comment