Israel’s objectives, Iran’s calculations and Hezbollah’s survival choices

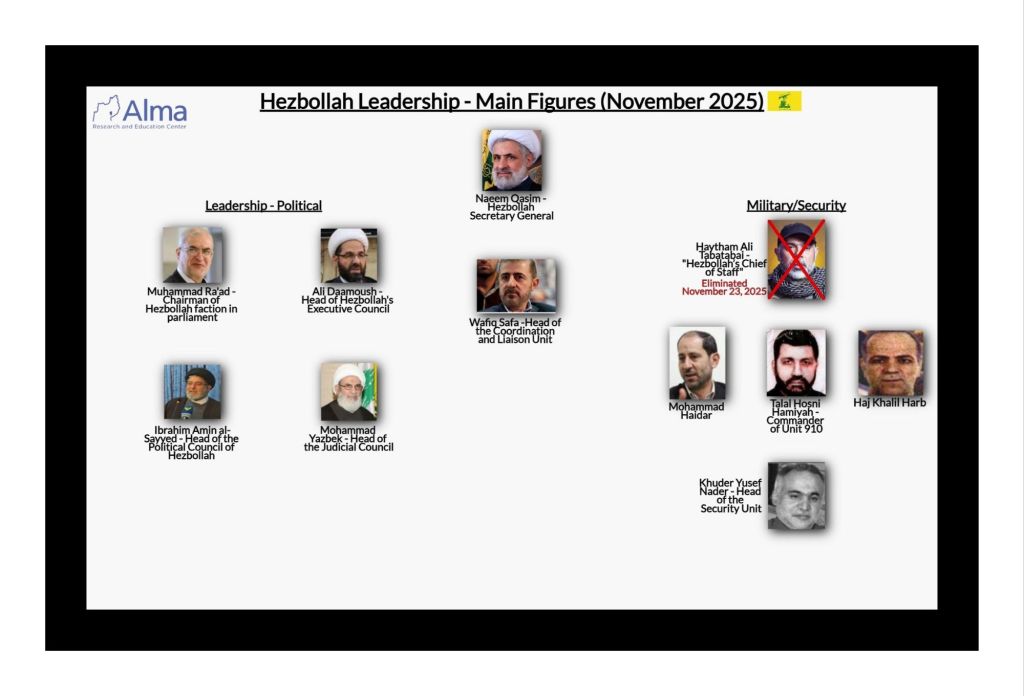

Haytham Ali Tabatabai’s killing in Beirut marks a structural inflection in the resistance axis’s operational and political posture across Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. Hezbollah’s command losses and the public rhetoric from Iran’s senior leadership expose the organisation to a simultaneous operational squeeze and political contestation that will determine whether Lebanon remains a space for proxy-enabled operations or begins a process of state reassertion and conditional reintegration. Mahmoud Kamati warned that “today’s aggression on the southern suburbs breaks a new red line” and emphasised that “the resistance is the one that decides how to respond to this aggression.” That remark captures the immediate dilemma: armed retaliation would reassert deterrence but risk national collapse, while restraint invites political delegitimation of armed autonomy.

*Netanyahu ordered the attack on Hezbollah chief of staff on recommendation of Defense Minister”)

Hezbollah retains significant armed and political capacity on the ground, yet its position no longer exists in a strategic vacuum. Naim Qassem declared that “we have the right to respond, and we will determine the timing,” anchoring the organisation’s posture in a legalistic claim to reciprocal force while signalling deliberate operational patience. Such timing discretion underscores the pragmatic calculus inside the movement: preserve coercive leverage while avoiding an escalation that could fracture the domestic coalition that sustains its political legitimacy. Concurrently, Iran’s parliamentary speaker Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf declared that “the aggressive hands must be severed from our region,” rhetoric that amplifies Tehran’s political backing for retaliatory frameworks while narrowing diplomatic manoeuvre space.

Operational realities constrain both options. Lebanon’s southern suburbs and Beirut’s periphery have become contested urban battlefields where high-precision targeting raises the cost of leadership survivability and imposes new force-protection requirements. Hezbollah’s internal adaptation to “high-tech wars” and its restructuring of command and logistics reflect learning from recent engagements, yet the group’s supply lines through Syria face increased exposure to interdiction, theft, and local fragmentation. Analysts note that Syria’s governance degradation has produced criminalised corridors that lower transaction costs for materiel transfer but increase the risk of diversion and accidental escalation. Those trade-offs mean that resupply is possible but risk-intensive, and that sustained rearmament at pre-war tempo would require resources and secure lines that Tehran may struggle to provide at scale.

Iran’s strategic posture has hardened rhetorically and organisationally. Senior Iranian commanders assert preparedness for coordinated operations and emphasise contingency plans designed to impose strategic costs if further strikes occur. Ayatollah Khamenei’s commentary framed recent confrontations as defensive successes while stressing national unity and the role of the resistance as a central deterrent mechanism. Tehran’s public posture aims to deter further decapitation strikes and reassure proxies, but it simultaneously reduces diplomatic room for de-escalatory signalling that appears ambiguous to regional audiences. The material constraint that sanctions and economic stress impose on Tehran’s ability to underwrite a wide, sustained rearmament campaign across multiple theatres therefore matters for credible commitment over time.

Lebanon’s domestic political calculus has shifted under intense public pressure and the prospect of conditional external funding. Gulf re-engagement and reconstruction capital are being offered on terms that attach state monopoly over force to aid and investment. Observers inside the region report that Lebanese political elites now face an acute choice between preserving Hezbollah’s autonomous arsenal and securing urgent economic lifelines for national survival. Ahmed al-Sharaa’s public comment that “we succeeded in expelling Iran and Hezbollah from Syria” encapsulates a broader regional appetite among some actors to reclaim sovereign control over territorial governance and logistics, particularly where foreign influence produced long-term instability.

Three plausible near- to mid-term scenarios arise from the current configuration of forces, resources and political incentives. The first scenario involves managed de-escalation under robust, verifiable international guarantees paired with conditional reconstruction funding. In that case, Hezbollah accepts operational limits and incremental demilitarisation in return for inclusion in the political process and social programs, while Lebanese state security capacities receive external support to enforce public order. Such a scenario requires credible third-party verification and durable security guarantees, neither of which currently exist at sufficient scale. The second scenario entails episodic tit-for-tat engagements, targeted assassinations and calibrated retaliation that stop short of all-out war but inflict substantial civilian and infrastructural damage. This outcome appears most likely given incentives on both sides to avoid full escalation while still signalling capability and resolve. The third scenario would see miscalculation or internal fracture precipitate large-scale civil or interstate war; such a rupture remains possible, particularly if armed actors lose control of escalatory dynamics or if external patrons opt for kinetic demonstrations of support rather than political restraint.

A second-order effect concerns the axis’s broader regional cohesion. The recent strikes and subsequent public Iranian declarations highlight fissures in the forward-defence model predicated on proxy depth and host-state permissiveness. Iran’s capacity to project sustainable materiel and organisational support across Lebanon, Syria and Yemen faces stress from economic constraints and from the political fatigue of local constituencies that increasingly prioritise recovery and governance over perpetual militarisation. Popular exhaustion among proxy constituencies reduces the political capital available for prolonged mobilisation, and that reality limits the depth of plausible escalation without widescale social dislocation in host societies.

For Israel and its partners, the operational environment now requires sustained expenditure on interception, intelligence and reserve mobilisation to absorb multi-axis salvos and to deter cross-border infiltration. Open-source reporting indicates significant Israeli concern about munitions depletion and manpower strain; those constraints favour calibrated strikes designed to degrade adversary command and control while avoiding a broader conflagration. Reuters For the United States and Gulf partners, the strategic opportunity lies in using conditional reconstruction funds and targeted security assistance to incentivise state reassertion. Effective use of such leverage depends on enforceable verification mechanisms and on the political will to sustain guarantees in the event of provocation. Money without verification will struggle to reshape long-standing coercive bargains.

The most immediate operational risk derives from the coupling of high-precision decapitation capabilities with the porous governance environment of adjacent theatres. Syria will continue to function as a logistics corridor that simultaneously enables proxy operations and generates unpredictable spill-overs through criminalised intermediaries. Yemen and the Red Sea theatre will remain leverage points for the axis to impose asymmetric costs should Tehran seek to diversify pressure beyond Lebanon. Those options complicate any straightforward pathway to containment and provide Tehran with asymmetric counters even while its conventional resupply capacity is constrained.

Direct quotations from principal actors make clear the stakes. Mahmoud Kamati’s insistence on coordination with the Lebanese state and the phrase “all possibilities are possible” reflect an active hedging strategy that preserves options. Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf’s public demand that the region cut off “aggressive hands” signals Tehran’s political commitment to deterrence even as resource limits persist. ISNA Naim Qassem’s refusal to surrender the group’s right to respond illuminates Hezbollah’s core preference for calibrated sovereignty through armed capacity. Those statements together show a strategic mix of deterrent signalling, hedging and political bargaining rather than a coherent pathway to total submission or irreversible victory for either camp.

“America is more despised every day. Wherever they’ve interfered, there’s war, genocide, and destruction.”

“They claim Iran sent a message to America. It’s a complete lie.”

“The U.S., controlled by the Zionist clique, is ready to spark wars anywhere, even spreading this to Latin America.”)

Iran and Russia have opened discussions on a formal security arrangement that several regional analysts describe as a move toward a NATO-style pact, and those talks carry implications that reach across every active theatre. Dmitry Peskov spoke of a “dynamic partnership” while avoiding any formal treaty language, yet Russian security circles have indicated an interest in structured defence coordination as both states face shared pressure from the United States and its allies. Such an arrangement would grant Tehran a stronger deterrent shield and create deeper operational confidence for its regional partners, while raising fears in Israel and Washington that a firm mutual-defence clause would embolden proxy activity and hinder timely pre-emptive action. A shift of this kind would compress decision windows during crises, increase the probability of rapid escalation, and further entrench a multipolar security order that limits the effectiveness of coercive military pressure against Iran.

Israeli military policy has moved toward a posture that regional observers long described as expansionist, with public plans for the absorption of areas in southern Lebanon and parts of Syria presented by officials aligned with the current government. Those ambitions frame demobilisation and demilitarisation demands not as narrow security measures but as steps required to remove obstacles to long-term territorial consolidation. Resistance groups understand those objectives, and their reading of the strategic map places Israeli actions within a larger design Netanyahu has publicly presented known as “The Greater Israel Plan” rather than isolated tactical choices. That perception shapes their refusal to disarm even under sustained pressure, as they treat any loss of armed capacity as an invitation for permanent strategic displacement rather than a pathway to negotiated stability.

Iran and its partners interpret Israel’s recent strikes and cross-border actions as part of a broader attempt to break the resistance axis, subdue Iran through pressure and decapitation, and secure uncontested freedom of action across Lebanon, Syria and the wider region. The harder target remains Iran itself, which holds the industrial base, missile depth and national cohesion that make outright strategic subjugation improbable, while the weaker links lie among overstretched resistance groups that face local fatigue and fragile logistics. The regional balance now rests on competing long-term projects: an Israeli agenda that seeks to secure expansion and strategic depth, and an Iranian-led network that views any rollback as an existential threat requiring a sustained deterrent posture. Those opposing aims will shape escalation thresholds and reduce the viability of narrow containment strategies, leaving the region to navigate a prolonged contest where deterrence, territorial ambition and political survival remain tightly interlocked.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment