How Abandoning the JCPOA Removed Containment To Make Way For Confrontation

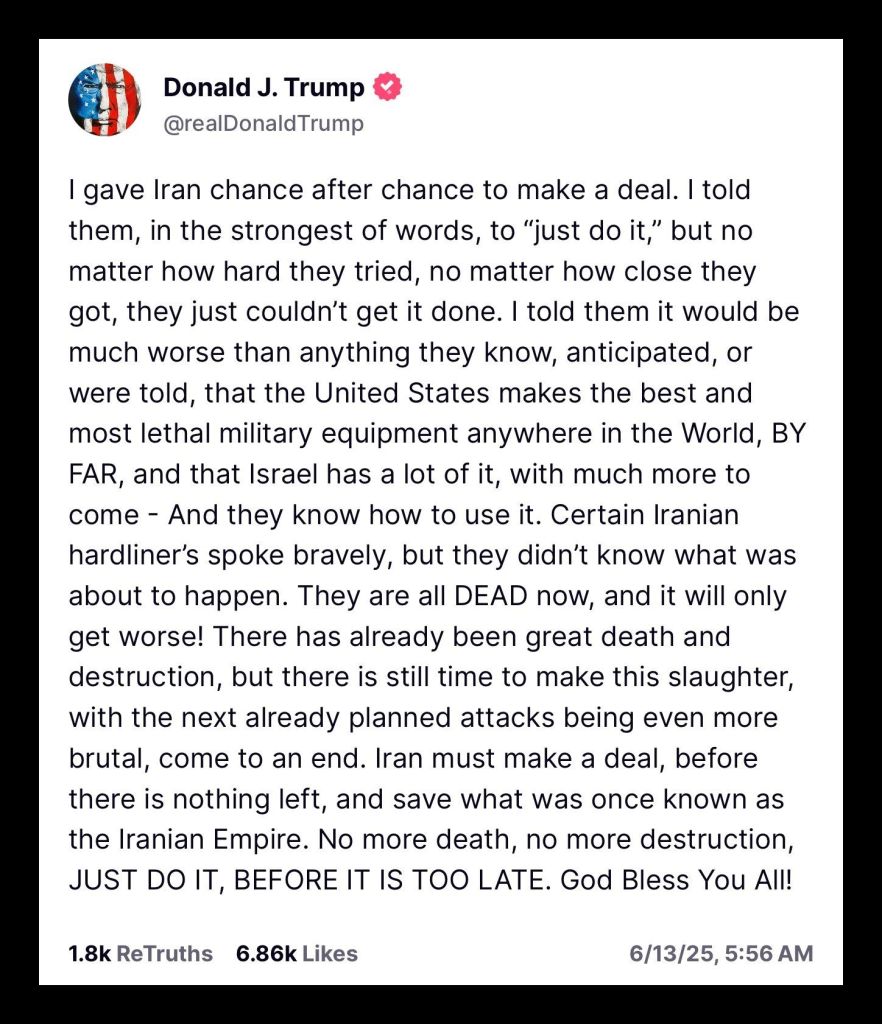

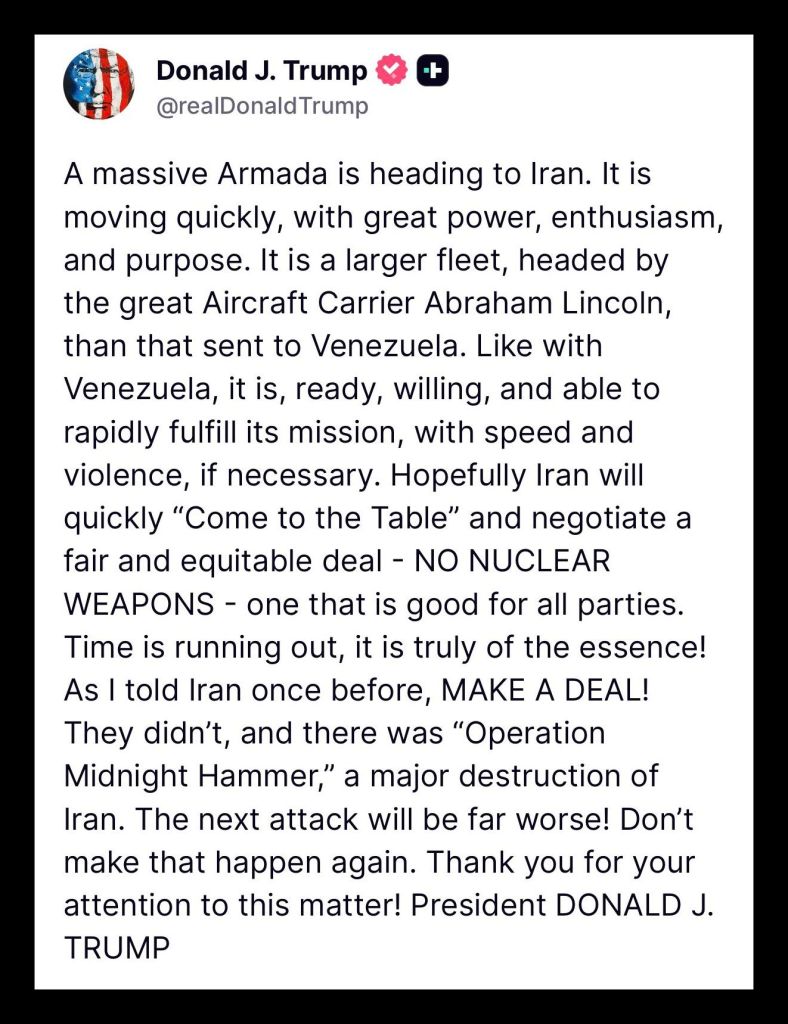

For several years, Donald Trump has repeatedly insisted that Iran must “make a deal,” but his most recent demand has been framed with unusual urgency. He has publicly declared that Iran has until today to comply, warning of severe consequences if it does not.

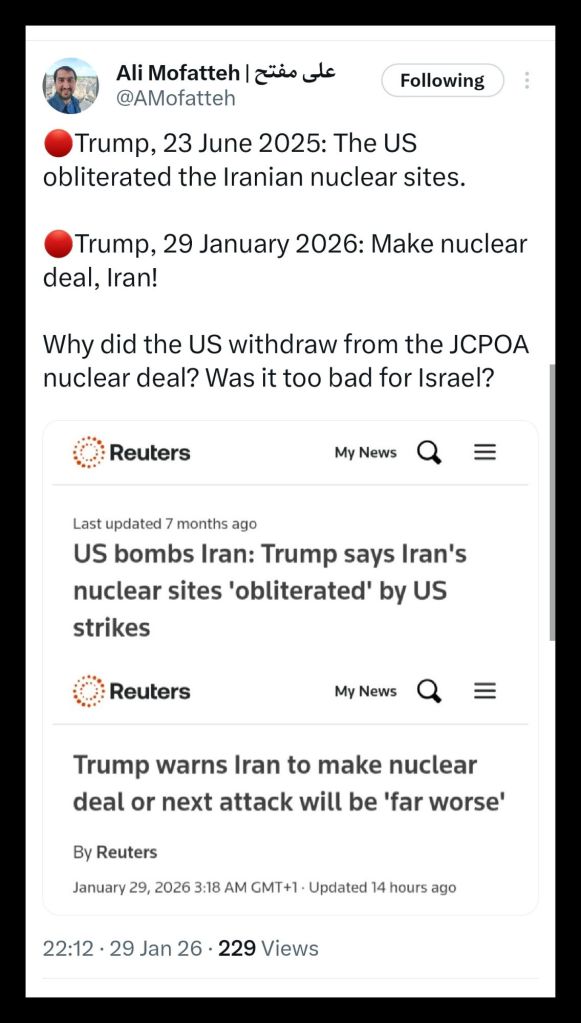

This deadline follows a familiar pattern in which the stated justification for confrontation shifts over time. Only months ago, the emphasis was on alleged Iranian repression of domestic protests. Before that, it centred on conventional missile development and regional militancy. Now, once again, the focus has returned to nuclear enrichment. In each iteration, confrontation is presented as the inevitable result of Iranian behaviour, rather than the consequence of American policy choices. That demand obscures a central fact of recent diplomatic history: Iran already made a deal with the United States and much of the international community, and it was Washington that abandoned it. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, concluded in 2015, represented one of the most comprehensive nuclear nonproliferation agreements ever negotiated, supported not only by the United States but also by the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Russia, China, and endorsed unanimously by the United Nations Security Council.

The JCPOA was designed with a narrow and explicit purpose: preventing Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon while reintegrating the country into the global economic and diplomatic system. It imposed strict technical limits on Iran’s nuclear program, including caps on uranium enrichment levels, restrictions on centrifuge deployment, and reductions in fissile material stockpiles. According to repeated assessments by the International Atomic Energy Agency, these measures extended Iran’s nuclear breakout time to at least twelve months, providing ample warning of any potential violations. Ernest Moniz, the former U.S. secretary of energy who helped negotiate the agreement, described it as placing Iran’s nuclear program “in a box with a lid and a lock.”

The agreement also included one of the most intrusive inspection regimes ever accepted by a sovereign state. The IAEA was granted continuous monitoring authority and a structured process for resolving disputes over undeclared sites. In return, Iran was promised substantial sanctions relief, including access to frozen financial assets and reintegration into international banking and trade systems. Although the deal required trust on both sides, most nuclear experts agreed that it made covert weaponization extraordinarily difficult without early detection.

Beyond its technical provisions, the JCPOA carried significant political implications within Iran itself. It strengthened moderate political forces who argued that engagement with the West offered a viable alternative to perpetual confrontation. President Hassan Rouhani invested considerable political capital in defending the agreement domestically, portraying it as a pathway toward economic normalization and reduced hostility. As analysts such as Vali Nasr have noted, the deal represented not only a nuclear compromise but also a bet on the possibility of gradual political moderation.

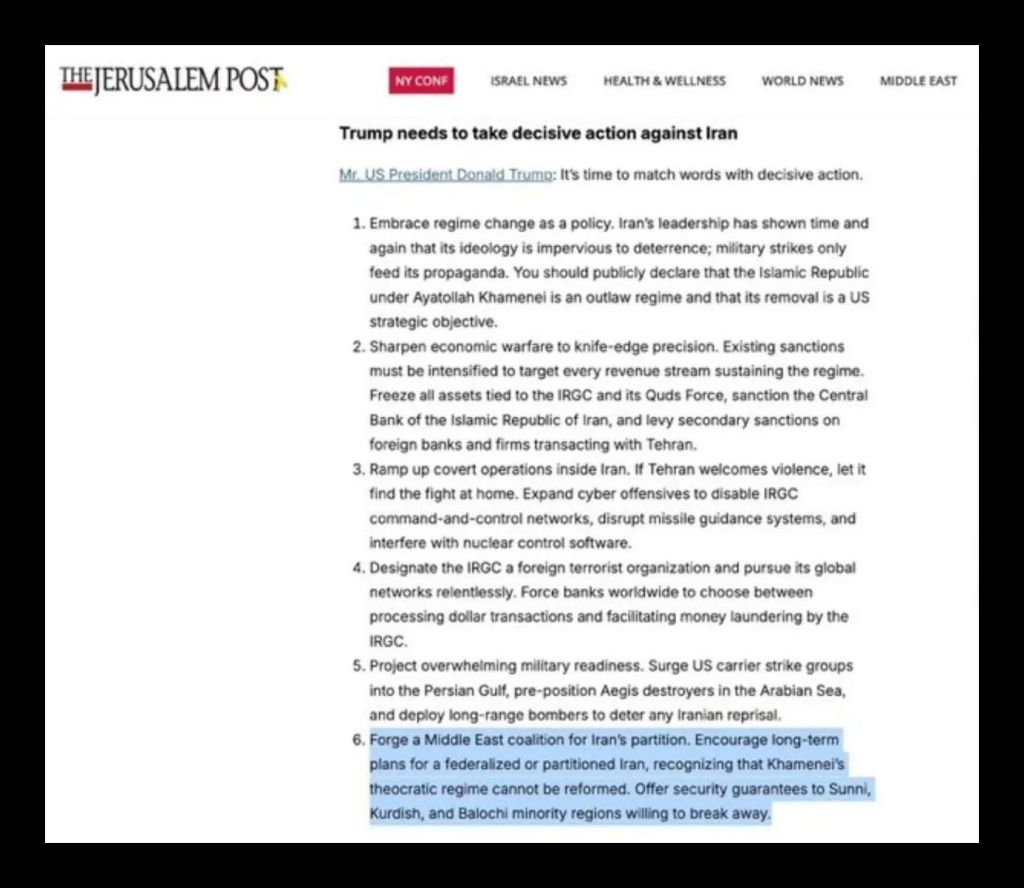

That bet depended entirely on the credibility of American commitments. Opposition to the JCPOA within the United States was driven less by its technical merits than by ideological resistance to diplomacy with Iran. Conservative media outlets portrayed the agreement as a financial giveaway, despite the fact that the funds involved belonged to Iran prior to sanctions. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly denounced the deal as a historic mistake and lobbied U.S. lawmakers against it in an unprecedented address to Congress during Barack Obama’s presidency.

In 2018, Trump withdrew from the JCPOA, branding it “the worst deal ever,” despite the absence of verified Iranian violations. European governments, along with Russia and China, attempted to preserve the agreement without U.S. participation, but these efforts were undermined when Washington reimposed sanctions and introduced new measures targeting Iran’s economy. According to the IAEA, Iran remained compliant for roughly a year after the U.S. withdrawal, even as promised economic benefits failed to materialize. Only then did Tehran begin incrementally breaching enrichment limits that had been suspended under the agreement.

The domestic consequences inside Iran were swift and severe. Rouhani’s political credibility collapsed, and engagement with the West came to be viewed as naïve and strategically reckless. In subsequent elections, Iranian voters elevated Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline cleric openly hostile to accommodation with the United States. Under Raisi’s leadership, Iran accelerated its nuclear activities, expanded support for regional proxies, and adopted a far more confrontational posture toward the West.

Much of today’s instability across the Middle East, from Lebanon and Yemen to the broader confrontation involving Israel, cannot be separated from the collapse of the JCPOA. Iran’s increased alignment with Russia and China and its expanded regional activities reflect strategic recalibration following diplomatic isolation rather than an inevitable ideological trajectory. As Mohamed ElBaradei, the former head of the IAEA, later observed, Iran complied with the deal until compliance ceased to serve any rational purpose.

Against this background, the justifications offered for potential military action against Iran have shifted repeatedly. At various points, American and allied officials have cited nuclear enrichment, ballistic missile development, domestic unrest, oil market stability, and regional militancy. These shifting rationales resemble earlier interventionist narratives applied in Iraq, Libya, and Venezuela, where stated objectives evolved as previous arguments failed to mobilize sufficient political support. The consistency lies not in the explanations but in the underlying pressure for confrontation.

Iran’s geopolitical position, population size, and energy reserves make it central to the balance of power in the Middle East. Its independent political system limits external dominance across the region and constrains broader efforts at unipolar control. From this perspective, demands that Iran “make a deal” disregard both the prior agreement and the credibility deficit created when the United States unilaterally abandoned it.

Strategic analysis suggests that the long-term objective has extended beyond nuclear nonproliferation. It has involved efforts to neutralize Iranian autonomy through regime change, state fragmentation, or prolonged internal instability. The Libyan precedent demonstrates how state collapse can eliminate strategic resistance without formal occupation, reshaping regional alignments at immense human cost.

The current insistence that Iran must rapidly accept a new agreement raises a basic credibility problem that cannot be resolved through threats alone. The previous agreement was honoured by Iran, verified by international inspectors, and abandoned unilaterally by the United States without evidence of material breach. Since then, the stated reasons for confrontation have shifted repeatedly, moving between nuclear activity, missile development, internal protests, oil markets, and regional alliances. This pattern suggests that the absence of a deal may not be the failure of diplomacy, but a condition increasingly treated as strategically useful. For Iranian policymakers, the lesson is clear that compliance does not guarantee stability, relief, or long-term engagement. Under these conditions, demands for trust ring hollow, while escalation becomes structurally embedded in the relationship. The risk now is not simply another failed negotiation, but the normalisation of war as an instrument of regional order management.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

Leave a comment