Shifting great power relations, Asia’s strategic choices could reset the global order next year

Asia approaches 2026 holding decisive economic and political weight that no previous period has combined so fully. Purchasing power parity data from the International Monetary Fund places Asia at roughly half of global output, while the United States accounts for about fifteen percent, a sharp decline from the early post–Cold War period. Economic scale matters because trade patterns, capital flows, and production networks follow gravity rather than declared alliances. Decisions taken by Asian governments now shape the operating environment of the entire international system.

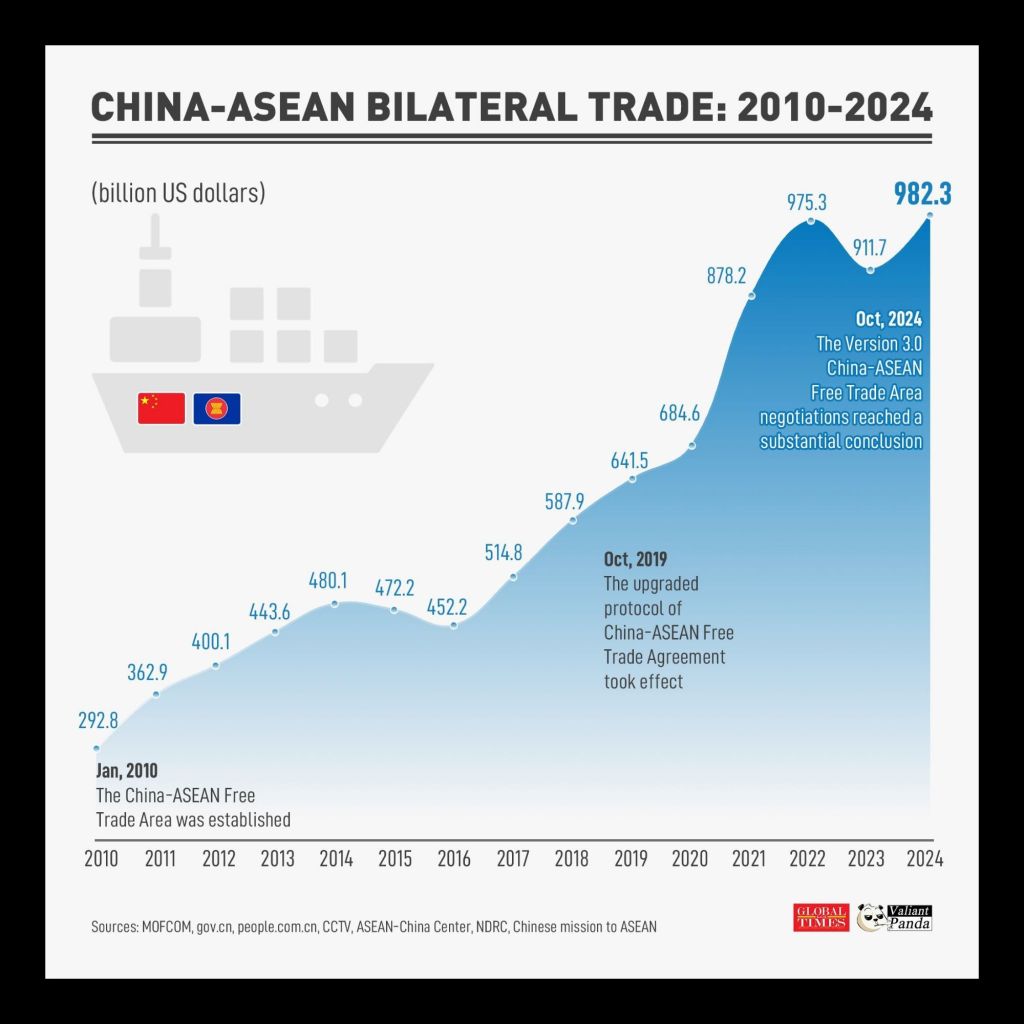

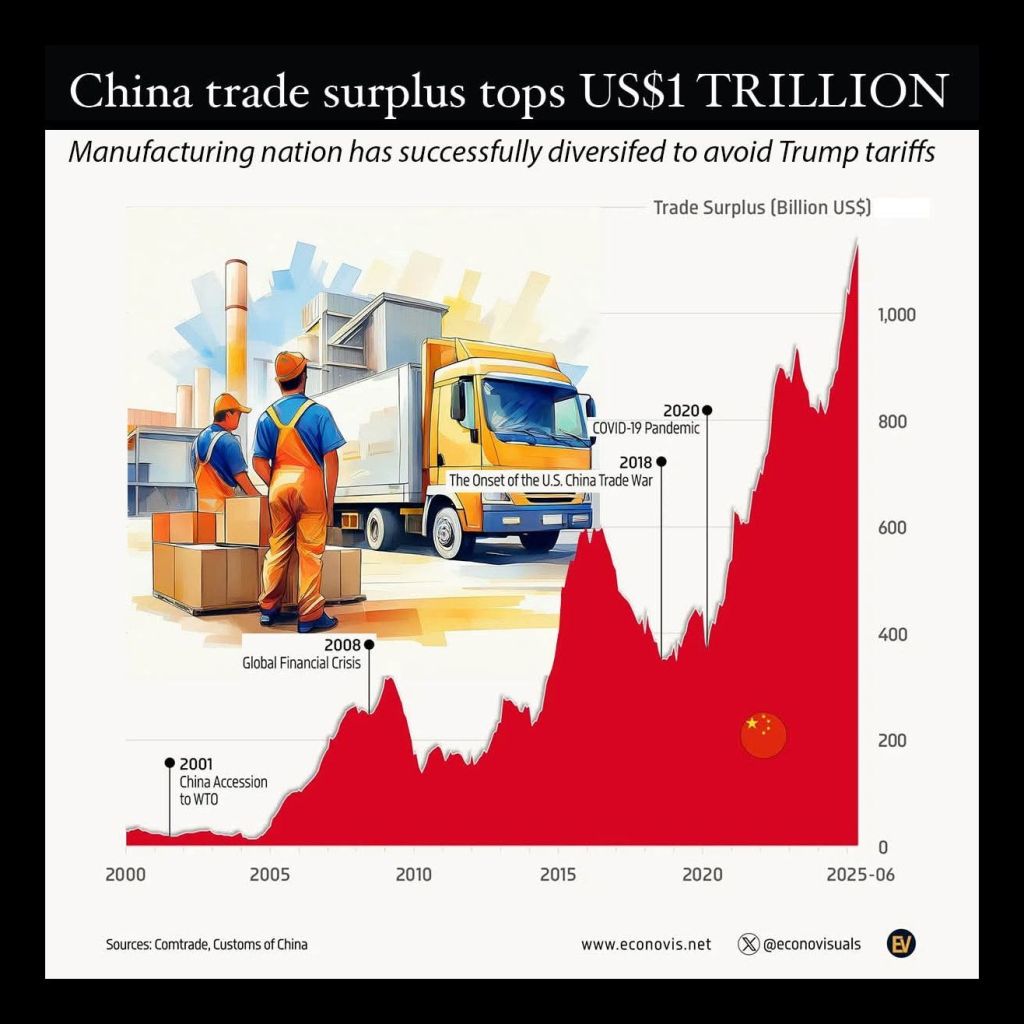

Trade relationships illustrate this shift with unusual clarity. China serves as the largest trading partner for more than one hundred and twenty countries, including almost every Asian economy. The United States holds that position for fewer than sixty countries, largely concentrated in Europe and parts of Latin America. Within Southeast Asia, more than sixty five percent of trade occurs inside Asia itself, while trade with the United States remains below ten percent. These figures constrain strategic rhetoric because governments dependent on regional trade cannot easily subordinate economic survival to external security preferences.

International Monetary Fund data alone does not explain political behaviour, yet scale imposes limits on choice. Kishore Mahbubani of the National University of Singapore has argued that Asian states pursue autonomy rather than alignment because economic interdependence with neighbours exceeds any benefit from distant security guarantees. He wrote that Asian leaders “cannot afford ideological loyalty tests when supply chains and growth depend on regional stability.” Such reasoning reflects structural pressures rather than sentiment.

American credibility across Asia has weakened through long military campaigns that produced disorder rather than security. Since 2001, United States wars have consumed more than eight trillion dollars and ended with state collapse in Iraq and Afghanistan. Independent security analyst Andrew Bacevich described these outcomes as evidence that American power “expends vast resources while delivering meagre strategic returns.” Asian governments observe these results while assessing claims that the United States remains a reliable security provider.

Economic interdependence now collides with attempts at technological and financial separation. Over seventy percent of global manufacturing value chains operate within Asia, while United States manufacturing output has fallen below twelve percent of the global total, compared with twenty eight percent at the turn of the century. Production networks formed over decades cannot be unwound quickly without cost. Studies examining United States–China decoupling estimate annual losses of one to two percent of United States GDP, while Chinese losses appear smaller and increasingly offset through regional trade expansion.

Semiconductor production demonstrates this imbalance with precision. More than eighty percent of global fabrication capacity sits in East Asia, spanning Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and mainland China. United States military systems depend on chips fabricated in these locations. Even analysts supportive of American industrial policy concede that domestic capacity cannot replace Asian production within a decade. Richard Baldwin of the Graduate Institute in Geneva noted that “supply chains are not Lego blocks that can be rearranged at will without breaking the system.”

Financial power shows similar limits. The share of United States dollars in global foreign exchange reserves has fallen from roughly seventy one percent in 1999 to about fifty eight percent today. This decline accelerated after repeated sanctions episodes that signalled political conditionality attached to reserve holdings. Economist Michael Hudson has argued that sanctions transformed the dollar from a neutral medium into a strategic weapon, prompting diversification rather than submission. Asian central banks responded by increasing holdings of gold, regional currencies, and bilateral settlement mechanisms.

Institutional development reflects these preferences. Asian-led bodies such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the expanded BRICS framework operate without United States veto power. Participation does not require ideological alignment, only material contribution and mutual benefit. Former Indian diplomat M K Bhadrakumar described these institutions as “practical vehicles for sovereignty preservation rather than instruments of bloc politics.” Their growth reduces reliance on Western-dominated systems without demanding open confrontation.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations members illustrate this approach through careful balancing. Regional governments avoid formal military alignment while deepening economic ties across Asia. Defence cooperation with external powers continues, yet trade and investment policy remains anchored in regional integration. Such behaviour follows incentives rather than rhetoric, shaped by supply chains, demographics, and infrastructure.

American policy responses often misread these dynamics by framing choices as loyalty tests. John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago has argued that multipolar systems reward flexibility and punish ideological rigidity. Asian states operating within a multipolar environment maximise options by avoiding exclusive commitments. Pressure to choose sides risks accelerating the very erosion of influence such pressure seeks to prevent.

By 2026, cumulative effects of these trends converge. Asia’s economic mass, trade integration, manufacturing dominance, and institutional development constrain external influence more tightly than any formal alliance shift could achieve. Strategic choices taken by Asian governments next year may not announce a new order, yet they will normalise one already forming. The global system moves less through declarations than through repeated practical decisions that redefine what remains possible.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment