Manufactured internal dissent, external pressure, and the endurance of a layered Iranian political order

The demand for regime change in Iran has become a litmus test for political coherence in the present international order. Advocacy for the overthrow of the Iranian state, when detached from the material balance of power that governs outcomes, functions as support for the expansion of United States imperial authority regardless of declared intentions. No plausible pathway exists whereby the Iranian government could be removed without the decisive intervention of the United States and its allied security architecture, and any outcome of such an intervention would necessarily entrench Washington’s influence over whatever political structure followed. Power vacuums do not remain unfilled, and Iran does not possess a unified internal force capable of seizing and stabilising authority while excluding external patrons with overwhelming coercive capacity.

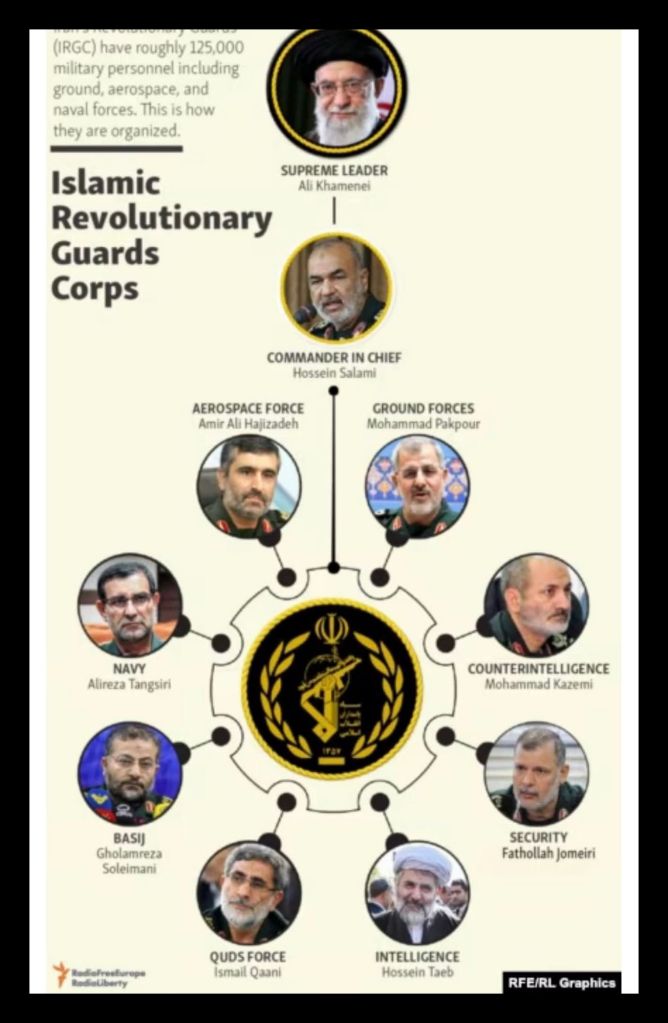

Iran’s political system was designed after 1979 to prevent collapse through decapitation or mass unrest. Authority does not reside in a single individual despite the prominence of Ali Khamenei. The Islamic Republic operates through a layered structure combining elected institutions, clerical oversight, parallel security organisations, and ideological militias. This architecture was shaped by the experience of revolution, war, and sustained external pressure, and it reflects an assumption of permanent hostility from outside powers rather than episodic crisis. Any analysis that treats the Iranian state as fragile misunderstands how deliberately redundancy and coercive depth were built into the system.

Recent protests across Iran emerged from severe economic distress driven by inflation, currency collapse, water shortages, electricity failures, and sanctions-induced isolation. These grievances are genuine and widely shared. Public anger has been visible in numerous cities, yet scale and momentum remain limited when compared with previous episodes of unrest. Israeli security analyst Ehud Ya’ari noted that nationwide protest centres numbered roughly sixty, concentrated primarily in eastern Tehran, far below the hundreds observed during earlier peaks of mobilisation. Demonstrations continued without expanding into a mass national movement capable of overwhelming state control mechanisms.

The state response followed a familiar escalation pattern. Protests were formally reclassified as terrorism, signalling that lethal force would be authorised. Such declarations carry weight in a system where internal security forces have demonstrated willingness to act decisively. Ya’ari stated that no meaningful fractures appeared within the government, the regular armed forces, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or the Basij militia. Signs of hesitation were observed but remained marginal, insufficient to disrupt command cohesion or operational effectiveness. This assessment aligns with structural realities rather than ideological preference.

The opposition’s inability to produce a credible internal leadership has further constrained protest dynamics. The promotion of Reza Pahlavi by Western media and diaspora networks has not translated into authority on the ground. Ya’ari described Pahlavi as attempting and failing to function as a guiding figure comparable to Ayatollah Khomeini’s role from exile in 1978. No mechanism exists through which his statements generate coordinated action inside Iran, and perceptions of alignment with foreign intelligence services severely undermine domestic legitimacy.

Technological assumptions underlying expectations of protest success have also collapsed. The belief that satellite internet could provide an unjammable alternative communication backbone proved false. Iran deployed coordinated electronic warfare systems capable of disrupting Low Earth Orbit satellite links, including Starlink terminals smuggled into the country. According to monitoring cited by IranWire, initial disruption rates of approximately thirty percent rose above eighty percent within hours. Digital rights researcher Amir Rashidi of the Miaan Group stated that he had never observed such comprehensive suppression of satellite connectivity across two decades of research. This marked a shift in state capacity and demonstrated that external technological fixes cannot substitute for internal political organisation.

The electronic warfare operation carried broader strategic implications. Reports indicated that Chinese and Russian technologies were integrated into Iran’s jamming systems, transforming the country into a live-fire testing environment for countering satellite-based communications. Prior assumptions that constant orbital movement and frequency hopping rendered such systems resilient were invalidated. Unlike Russian jamming efforts in Ukraine, which SpaceX mitigated through rapid software updates, Iran’s multi-layered state-level coordination presented a fundamentally different challenge. The notion of an unblockable digital lifeline for insurgent mobilisation no longer holds.

Western political rhetoric escalated as protests unfolded. Donald Trump issued public warnings stating that the United States was prepared to intervene if Iranian authorities continued lethal repression. Statements that the United States was “locked and loaded” and that shooting protesters would trigger American retaliation raised expectations of imminent military action. Yet these declarations collided with strategic constraints. Iran possesses substantial retaliatory capabilities across the region, and any direct strike would invite immediate responses against American bases and allied infrastructure.

Iran’s military posture reflects long-term preparation for such contingencies. Missile production and refurbishment have continued despite severe civilian shortages. Liquid-fuel systems such as Shahab-3, Emad, Ghadr, and Soumar missiles are reportedly being reconditioned at scale, with estimates suggesting over one thousand missiles could be restored within six months. Missile cities remain operational and stocked, indicating that military prioritisation supersedes domestic economic relief. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Aerospace Force retains responsibility for these capabilities, reinforcing deterrence rather than enabling collapse.

Naval dimensions compound escalation risks. Iran maintains more than twenty submarines and extensive anti-ship missile inventories capable of threatening maritime traffic across ranges exceeding one thousand kilometres. Closure of the Strait of Hormuz would impose daily global economic losses measured in billions of dollars. Such actions would not remain symbolic, and regional spillover would be unavoidable. These realities sharply limit Washington’s appetite for direct confrontation.

American and Israeli stockpile constraints further reduce escalation credibility. More than ninety thousand tonnes of munitions were transferred to Israel and expended in Gaza and earlier strikes involving Iran. Replacement of air defence interceptors and precision munitions remains incomplete. Strategic planners must account for these shortages alongside other unresolved commitments, including Venezuela and Arctic territorial disputes. Iran, by contrast, expended only a fraction of its capabilities during the twelve-day conflict, preserving assets in anticipation of prolonged confrontation.

Iran’s internal security architecture remains central to regime durability. The Basij militia functions as the primary instrument of domestic control during unrest. Its active core numbers roughly ninety to one hundred thousand full-time personnel, with surge capacity reaching up to one million when auxiliary members are mobilised. Symbolic membership figures reaching into the millions obscure the operational reality, yet even conservative estimates reveal formidable capacity. Basij units are embedded within communities, enabling surveillance, rapid mobilisation, and enforcement of ideological discipline.

Should containment by police and Basij forces prove insufficient, escalation proceeds to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Established in 1979 to defend the revolution, the IRGC operates as a parallel military with independent land, sea, and air branches. Personnel estimates range between 125,000 and 190,000, augmented by Basij auxiliaries. The IRGC controls missile forces, oversees asymmetric naval operations, and manages external activities through the Quds Force. It answers directly to the Supreme Leader, bypassing civilian oversight on security matters.

The Quds Force remains influential despite losses suffered during mid-2025 strikes and the decapitation of allied leaderships. It continues to coordinate relationships across Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and residual Syrian networks. Its role in constructing Iran’s regional deterrence architecture ensures that any external assault triggers responses beyond Iran’s borders. This capability is structural, not contingent on individual commanders.

Proposals advocating decapitation strikes against Khamenei reflect profound misunderstanding. Khamenei functions not only as head of state but as a recognised Shia marja for millions across multiple continents. His death at foreign hands would be interpreted as a religious assault rather than a political intervention. The precedent of the Salman Rushdie fatwa demonstrates how religious decrees persist across decades, motivating individual action independent of state direction. Any attempt to eliminate Khamenei would radicalise networks rather than dismantle them.

Shia authority itself remains divided between political and quietist traditions. Ali al-Sistani represents a contrasting model centred in Najaf, emphasising moral authority without direct governance. Sistani’s influence during Iraq’s post-occupation transition illustrated restraint rather than militancy. Iran’s system, forged through violent revolution and consolidated under Velayat-e Faqih, differs fundamentally. Comparisons that assume Iraqi-style outcomes ignore divergent historical foundations.

The limits of military force against Iran are therefore structural rather than situational. Airstrikes cannot dismantle internal security apparatuses or prevent street-level repression. Occupation would require forces exceeding those deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan, confronting an adversary with extensive combat experience and popular nationalist legitimacy against foreign invasion. No political constituency in the United States supports such a commitment.

Strategic focus further constrains policy. Washington’s primary long-term objective remains competition with China. Engagements in Ukraine already strain resources and attention. Opening a full-scale conflict with Iran would undermine broader strategic priorities rather than advance them. Sanctions remain the preferred tool, yet decades of pressure have produced adaptation rather than collapse.

Iran is not Venezuela. It is not a state organised around a single leader or dependent on external security guarantees. It is a layered system engineered to absorb shock, enforce internal discipline, and retaliate externally when challenged. Calls for regime change that ignore these realities amount to advocacy for imperial expansion under the guise of moral concern.

I thought I would make some recommendations in this regard seeing that chaos is spreading undermining peaceful coexistence. I am opposed to racist hierarchy, imperial domination, and colonial practice, change must begin with acceptance of sovereign equality as a binding principle rather than a rhetorical device. International order cannot be sustained where power determines legitimacy and where coercion substitutes for consent in resolving political disputes. States that claim leadership responsibility must subject themselves to the same legal and moral standards they impose on others, including compliance with the United Nations Charter prohibition on aggression, collective punishment, and coercive regime change.

Economic sanctions that function as collective punishment should be dismantled or radically constrained through multilateral legal review. Measures that target entire populations for political leverage violate principles of proportionality and civilian protection embedded in international humanitarian law. Any remaining sanctions regimes should be narrowly tailored, time limited, transparently reviewed, and subject to independent humanitarian impact assessments conducted outside sanctioning governments’ influence.

External support for political change must be withdrawn where it undermines domestic self determination. Funding, training, or amplifying opposition movements from abroad distorts internal political development and delegitimises genuine social grievances. Political reform derives durability only when negotiated within national frameworks by actors accountable to their own societies rather than foreign patrons.

International technology governance must prohibit the weaponisation of communications infrastructure for political subversion. Satellite networks, digital platforms, and financial systems should not function as covert instruments of regime engineering. Binding norms are required to separate civilian technology provision from intelligence operations, ensuring that access does not become conditional on political alignment.

Military deterrence postures should be replaced with regional security arrangements based on mutual non aggression and confidence building measures. Permanent foreign military basing in sovereign states without democratic mandate entrenches dependency and reproduces colonial security relationships. Gradual drawdowns tied to regional arms control agreements would reduce incentives for escalation while respecting national autonomy.

Diplomatic engagement must be unconditional with respect to recognition of governments exercising effective control within their borders. Selective legitimacy based on ideological conformity reproduces racialised hierarchies of governance. Dialogue does not constitute endorsement, and refusal to engage entrenches hardline factions rather than empowering reformist currents.

International legal institutions must be strengthened rather than bypassed. War crimes accountability, sanctions authorisation, and dispute resolution should proceed exclusively through recognised multilateral mechanisms rather than ad hoc coalitions. Equal application of law is the minimum requirement for restoring credibility to global governance structures.

Finally, narratives framing non Western states as perpetual objects of intervention must be rejected across academic, media, and policy institutions. Analytical work should prioritise material structures, historical context, and agency of local populations rather than moral caricature. Respect for self determination requires patience, restraint, and acceptance that political outcomes may diverge from external preferences without constituting threats to international order.

Political change in Iran, if it occurs, will emerge from internal dynamics over extended timeframes, not from threats issued abroad.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a donation or cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment