The political economy consequences of turning financial infrastructure into weapons hence de-risking from America is a rational response to concentrated monetary power

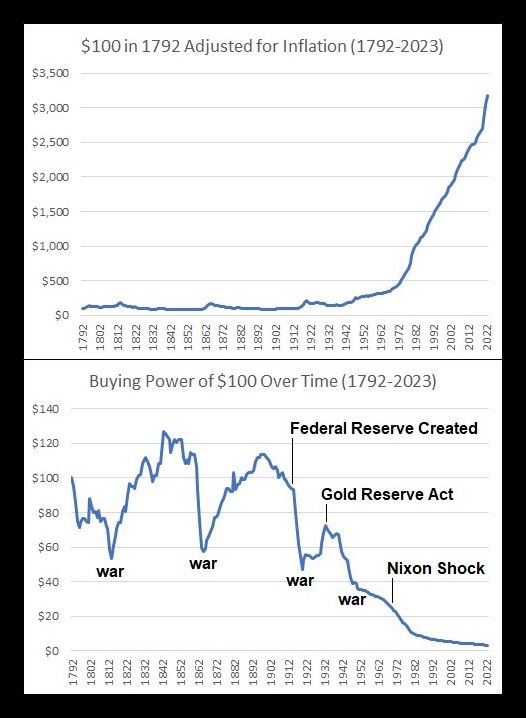

The United States dollar emerged as the core instrument of global trade and finance after 1945, supported by American industrial dominance, military reach, and the Bretton Woods framework. That position rested on confidence that access to dollar liquidity and payment rails would remain politically neutral for sovereign states acting within the international system. Over the past two decades, and with greater intensity since 2014, that assumption has eroded as Washington has converted monetary infrastructure into a coercive policy tool. Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr., former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, has described the United States as the principal adversary of its own currency, arguing that repeated sanctions and asset seizures have transformed the dollar from a shared utility into a strategic weapon. His assessment reflects a broader shift in official and academic analysis across non-Western capitals.

The freezing of approximately three hundred billion dollars of Russian central bank reserves in 2022 represented a decisive rupture. Previous sanctions regimes targeted individuals, firms, or commercial banks, often justified through legal mechanisms within Western jurisdictions. The Russian reserve seizure crossed a different threshold by placing sovereign monetary assets outside any wartime context under political confiscation. Former Bank for International Settlements economist Hyun Song Shin noted in private briefings that reserve safety constituted the final anchor of trust in the post-Cold War system, and that breach altered central bank risk calculations permanently. Chinese monetary authorities responded by accelerating reductions in United States Treasury holdings, continuing a trend that had begun after sanctions imposed on Iran and Russia earlier in the decade.

Batista has argued that the abusive use of instruments such as SWIFT exclusion and reserve immobilisation has forced states to reassess exposure to Western clearing systems. Russia responded by eliminating Western currencies from trade with Commonwealth of Independent States partners and expanding rouble settlement mechanisms. Iran deepened barter trade and local currency clearing arrangements with China and regional partners. India negotiated rupee-denominated oil settlements while expanding gold accumulation. According to data from the International Monetary Fund’s COFER database, the dollar share of disclosed global reserves declined steadily from above seventy percent in the early 2000s to near fifty-eight percent by the early 2020s, with the pace accelerating after 2022.

Financial de-risking has not remained confined to sanctioned states. Edward Luce has observed that allied economies now seek insulation from American unpredictability rather than deeper integration. The shift reflects a political reality recognised across European and Asian policy circles: alignment with Washington no longer guarantees protection from unilateral policy shocks. The Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary tightening cycles, combined with domestic American political volatility, have imposed external costs on partners without corresponding consultation. Former Bundesbank officials have privately warned that euro area exposure to dollar funding markets constitutes a structural vulnerability rather than a convenience.

Canada’s recalibration illustrates the phenomenon among close allies. Nearly three-quarters of Canadian exports historically flowed to the United States, a dependence once regarded as an advantage. Ottawa now seeks to reduce that share below fifty percent, redirecting trade toward China, India, and Southeast Asia. Mark Carney’s engagement with Beijing ahead of multilateral forums signalled a strategic hedge rather than ideological realignment. Similar discussions have taken place in Japan, South Korea, and within Gulf Cooperation Council states, where sovereign wealth funds have diversified away from dollar assets into Asian infrastructure, commodities, and regional currencies.

Dumping United States Treasuries represents the most extreme financial hedge, often described by central bankers as a nuclear option. Even without large-scale liquidation, marginal shifts matter. China’s Treasury holdings have fallen by hundreds of billions of dollars from their peak, replaced by gold accumulation at the People’s Bank of China and increased exposure to Belt and Road settlement mechanisms. Sergey Glazyev, Russian academic economist and former Eurasian Economic Commission official, has argued that multipolar currency zones now function as a defensive necessity rather than an ideological project. Regional payment systems, including China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System and Russia’s SPFS, operate redundantly alongside SWIFT, reducing systemic choke points.

The geopolitical implications extend beyond finance. Strategic hedging now includes security considerations traditionally monopolised by American guarantees. Luce notes that states have observed Washington’s differential treatment of nuclear-armed adversaries. North Korea’s regime survival contrasts sharply with the fate of non-nuclear governments subjected to regime change pressure. This observation has influenced defence planning debates in East Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Latin America. Academic studies from Seoul National University and Tel Aviv University have examined latent nuclear hedging as an insurance mechanism rather than an immediate proliferation intent.

China has interpreted American withdrawal from multilateral leadership as an opening rather than a threat. Beijing has positioned itself as a provider of infrastructure finance, development capital, and trade stability, particularly through the Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Chinese scholars such as Wang Huiyao of the Center for China and Globalization argue that reduced American reliability lowers resistance to alternative governance structures. The renminbi’s role remains constrained by capital controls, yet its use in energy trade with Russia and Gulf producers has expanded, supported by swap lines and clearing banks.

Against this backdrop, speculation has emerged regarding a reordering of global power centres, including claims that Jerusalem could become a new axis of authority under a so-called Pax Judaica. Historical precedent cautions against such linear interpretations. Power in the modern international system derives from production capacity, financial depth, demographic scale, and military logistics rather than symbolic centrality alone. Israel exerts disproportionate influence within American political institutions and regional security architectures, yet lacks the economic mass or monetary reach to anchor a global order independently. Scholars such as John Mearsheimer have emphasised that even hegemonic states struggle to sustain dominance without broad consent, let alone smaller actors embedded within larger alliances.

Nevertheless, Israel’s integration into American strategic planning affects perceptions in the Global South. Sanctions enforcement, Middle Eastern interventions, and diplomatic shielding at international forums have reinforced narratives that United States power operates through a narrow coalition rather than universal norms. This perception accelerates de-risking by states seeking autonomy rather than alignment. Latin American economists associated with UNCTAD have highlighted growing interest in regional development banks and currency pooling arrangements as alternatives to dollar dependence.

The cumulative effect of these trends suggests gradual erosion rather than abrupt collapse of dollar hegemony. Batista has acknowledged that the dollar will remain an important currency due to market depth and legal infrastructure. The difference lies in optionality. States now design systems assuming partial exclusion from Western finance rather than universal access. That assumption marks a structural change in global political economy. Trust once lost rarely returns fully, particularly when losses involve sovereign reserves accumulated over decades.

Policy debates within Washington increasingly recognise the dilemma. Former Treasury officials have warned that overuse of financial sanctions undermines long-term leverage. Academic research from Harvard and Stanford has modelled sanction fatigue and substitution effects, showing diminishing returns beyond initial shocks. Despite such findings, domestic political incentives favour visible punitive measures over slower diplomatic engagement, perpetuating the cycle identified by Batista.

The international system now resembles a fragmented landscape of overlapping monetary and security arrangements. De-risking from the United States does not imply hostility, but it reflects rational adaptation to concentrated power exercised without reciprocal restraint. Whether this evolution produces stability or prolonged volatility depends on institutional reform rather than symbolic shifts in geographic centres of authority.

Future stability would benefit from formal limits on reserve seizure and payment system exclusion through multilateral treaties involving central banks and settlement institutions. Re-establishing credible neutrality within core financial infrastructure would slow fragmentation and reduce incentives for parallel systems. Without such reforms, de-risking will continue irrespective of rhetorical commitments to order or alliance solidarity.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

This is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do this without your support. If you believe journalism should serve the public, not the powerful, and you’re in a position to help, becoming a PAID SUBSCRIBER truly makes a difference. Alternatively you can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv

Leave a comment