Understanding the Consequences of Ignoring Institutional Lessons and How Strategic Blind Spots Undermine National Stability

Iran’s recent crisis reflects a repeated failure to learn established lessons about survival under sustained external pressure. These lessons concern preparation for regime change operations, economic stabilisation as a security function, internal security consolidation, and deterrence credibility against external coercion. Each lesson has been presented to Iranian leadership through prior protest cycles, assassinations, sanctions episodes, and covert operations. Institutional learning has not followed experience, leaving vulnerabilities intact and exploitable.

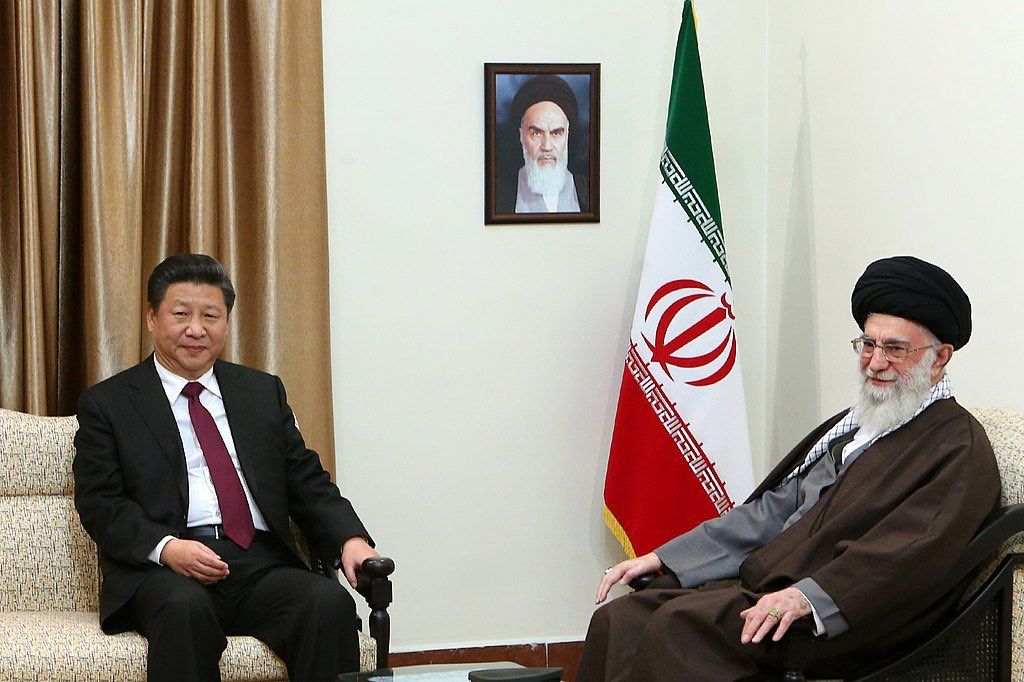

The January 2025 strategic partnership signed between Iran and Russia illustrated delayed recognition rather than early anticipation of these threats. Security coordination enabling the jamming of Starlink addressed a vulnerability already exploited during protest escalation. Protest networks relied on satellite infrastructure controlled by foreign private actors aligned with hostile geopolitical blocs. Glenn Diesen has consistently described modern regime change operations as systems focused on information dominance and economic exhaustion rather than overt invasion, noting that “control of narrative and connectivity precedes control of territory.” Iran permitted this architecture to operate until disruption became unavoidable.

Russian technical assistance constrained coordination between domestic protest organisers and external operatives, yet timing remained decisive. Intervention followed the maturation of protest logistics, messaging discipline, and external synchronisation. Analysts associated with the Valdai Discussion Club have repeatedly observed that early disruption of communication channels determines whether protest movements fragment or consolidate. Iran’s response reflected hesitation rather than technological incapacity.

Russian involvement extended into diplomatic containment aimed at preventing regional escalation rather than resolving Iranian internal weaknesses. Moscow engaged Israeli officials while discouraging actions that could trigger wider confrontation. Fyodor Lukyanov has characterised this approach as crisis postponement, writing that mediation often “buys time without altering underlying balances.” Iran benefited temporarily from restraint exercised by others rather than strength generated internally.

Economic mismanagement remained the primary structural driver of unrest. Inflationary pressure, currency instability, and declining purchasing power eroded confidence across social and regional lines. Iran retained access to immediate stabilisation mechanisms through strategic partners yet declined to deploy them. A short-term currency backstop of one to two billion dollars from China would have represented a modest intervention by international standards. Comparative studies from economists at the University of Cambridge on currency crises emphasise that early liquidity provision “halts expectation spirals before political mobilisation accelerates.”

Leadership paralysis replaced decisive intervention. Senior officials articulated grievances regarding sanctions without implementing emergency stabilisation measures. This inaction weakened administrative legitimacy and expanded the operational space for coordinated unrest. Political economy literature consistently links inflation shocks under sanctions regimes with protest escalation when corrective policy is delayed. Iran’s failure reflected governance choice rather than structural impossibility.

Argentina provided a recent and instructive comparison through rapid currency stabilisation supported by significant external financial backing. The International Monetary Fund agreed a US $20 billion Extended Fund Facility, immediately disbursing large tranches to bolster reserves and confidence, while the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank committed roughly US $12 billion and up to US $10 billion respectively, bringing total international support to about US $42 billion aimed in part at shoring up foreign exchange reserves and calming markets. Argentina’s coordinated fiscal compression, reforms, and external financing helped anchor expectations during periods when the peso had previously fluctuated sharply and inflation ran into triple-digit territory.

Iran’s currency, by contrast, experienced sustained depreciation under sanction pressure, restricted access to hard currency, and delayed policy intervention. External actors, including tightening sanctions and the withdrawal of correspondent banking relationships, compounded pressure on the exchange rate, while internal delays in stabilisation policy and absence of a credible short-term backstop allowed speculative momentum to persist. Iranian authorities did not deploy equivalent stabilisation mechanisms at scale, despite possessing longstanding strategic partnerships with China and Russia capable of providing bilateral liquidity buffers or currency support arrangements. The cumulative effect of external market pressure coupled with internal policy omission widened the gap between expectation and stability in the foreign exchange market.

Security failures compounded economic weakness. Armed groups exploited protest environments to conduct coordinated attacks against civilians and security forces. These actors transformed demonstrations into hybrid security operations combining civil unrest with organised violence. Analysts at the Institute for the Study of War have documented how protest movements serve as force multipliers for armed networks when external coordination remains uninterrupted. Iranian authorities confronted a security challenge exceeding public order management.

Counterintelligence weaknesses further exposed state vulnerability. Israeli intelligence operations penetrated Iranian territory repeatedly, eliminating senior figures with precision. Such operations reflected systemic detection and disruption failures rather than isolated breaches. Comparative security analysis frequently contrasts Iran’s penetration exposure with states maintaining near-total internal control. North Korea provides a relevant example of comprehensive internal security discipline preventing sustained external infiltration.

North Korea’s experience demonstrates that deterrence rests on clarity as much as capability. Possession of strategic weapons removed ambiguity regarding regime survival and eliminated expectations of negotiated political change. Pyongyang does not balance deterrence with diplomatic compromise, nor does it signal openness to restructuring under external pressure. This clarity raised intervention costs beyond acceptable limits and confined external action to containment rather than transformation. Iran’s approach differed by maintaining negotiations over core security issues, preserving ambiguity that encouraged continued coercion rather than restraint.

The interaction between economic weakness and security vulnerability produced a repeating destabilisation cycle. Economic distress expanded protest participation. Protest environments enabled armed infiltration and foreign coordination. Armed operations undermined state authority and intensified insecurity. Insecurity further damaged economic confidence and investment conditions. Leadership failure to disrupt this cycle allowed repetition across successive crises.

Private technological power amplified these dynamics. Elon Musk’s control over Starlink illustrated how private infrastructure aligns with geopolitical objectives during conflict. Platforms ceased functioning as neutral utilities once deployed within contested political environments. Scholars at the Quincy Institute have warned that privatised infrastructure increasingly functions as an extension of state power during hybrid conflict. Iran failed to anticipate this convergence before unrest escalated.

Strategic denial regarding regime change intent weakened Iranian preparation at the highest levels of decision making. United States policy toward Iran showed continuity across administrations, with sanctions, covert pressure, and military signalling aimed at long-term weakening rather than negotiated coexistence. Iranian leadership continued to interpret diplomatic engagement as evidence of Western flexibility, while Western actors treated Iranian willingness to compromise as leverage to extract further concessions. This misreading encouraged delay and hesitation instead of structural preparation for confrontation.

Iran attempted neither full confrontation nor full economic realignment. Diplomatic outreach toward the West continued despite repeated evidence that negotiations functioned as pressure mechanisms rather than settlement pathways. At the same time, domestic economic management failed to compensate for sanctions through deep integration with non-Western partners. Trade, investment, and development opportunities with China, Russia, India, and the broader Global South remained underexploited despite available channels. This dual failure left Iran exposed externally and dissatisfied internally.

A clear strategic division of responsibility never emerged. Civilian leadership continued to pursue accommodation abroad without securing tangible relief, while military institutions remained embedded within the domestic economy, distorting incentives and efficiency. An alternative model existed. Russia under Vladimir Putin separated confrontation from accommodation, refusing compromise on battlefield and security matters while maintaining economic openness toward China, India, and other non-Western partners. This arrangement stabilised domestic conditions and sustained public tolerance for prolonged external pressure.

Iran did not adopt a comparable structure. Foreign policy remained divided between rhetorical defiance and practical concession, producing signals of uncertainty rather than resolve. Economic governance remained constrained by institutional overlap, limiting growth and undermining living standards. Leadership age and exhaustion further reduced capacity for decisive restructuring. Strategic adjustment requires energy, coherence, and willingness to reassign authority. Absence of these qualities sustained denial rather than adaptation.

Coordination with China and Russia developed in response to crisis rather than through permanent institutional integration. Security cooperation accelerated after unrest escalated, including the provision of advanced radars, electronic warfare systems, and jamming capabilities, rather than preceding the threat environment. Chinese financial and digital control capabilities, demonstrated through rapid currency defence and internal stabilisation measures, were not deployed to counter inflationary pressure or market panic inside Iran. Russian experience in countering information warfare and protest-driven destabilisation informed specific tactical responses but was not embedded into standing Iranian security and governance structures. The pattern reflected episodic assistance instead of continuous joint planning across economic, cyber, and intelligence.

Internal governance failures widened exposure to foreign exploitation and sustained internal destabilisation pressures. Corruption and economic misallocation weakened administrative control and eroded confidence across key social and regional constituencies. Ethnic and regional grievances among Kurdish, Azeri, Balochi, and Afghan-linked communities were repeatedly exploited for recruitment, logistics, and local intelligence penetration. United States and Israeli strategy has long aimed at weakening Iranian territorial cohesion through fragmentation, encouraging separatist pressure points along these ethnic fault lines. Uneven development in peripheral regions created conditions where armed networks could embed themselves within existing social and economic grievances.

The recent crisis ended without escalation because outside actors chose delay over confrontation, not because underlying weaknesses were resolved. Mediation slowed events while economic disorder, security gaps, and institutional inertia remained unchanged. Each repetition of unrest leaves the state more exposed, more penetrated, and less credible. Historical experience shows that governments facing sustained external pressure are not granted unlimited chances to correct accumulated failures.

Iranian leadership now confronts a familiar moment where past failures to learn carry immediate strategic cost. Economic disorder, visible internal insecurity, and unresolved deterrence gaps have signalled weakness to adversaries already preparing further pressure. United States and Israeli military planning has never paused, and recent unrest reinforced assessments that Iran remains internally fragile. Preparation for renewed attack requires disciplined economic control, restored internal order, and credible deterrence, rather than continued reliance on rhetoric or external restraint.

Colonel Thorne)

Iran should treat economic stabilisation as an immediate security priority rather than a secondary policy concern. Institutionalised coordination with China and Russia across financial, cyber, and intelligence domains should replace reactive engagement. Counterintelligence reform must prioritise penetration denial and internal discipline. Strategic deterrence posture requires reassessment based on comparative cases demonstrating intervention avoidance. Learning from repeated exposure, rather than enduring repetition, remains the decisive requirement for state survival.

Authored By: Global GeoPolitics

Thank you for visiting. This is a reader-supported publication but shadow banned by the overlords. I cannot do this without your support. You can support by way of a cup of coffee:

buymeacoffee.com/ggtv or

Leave a comment