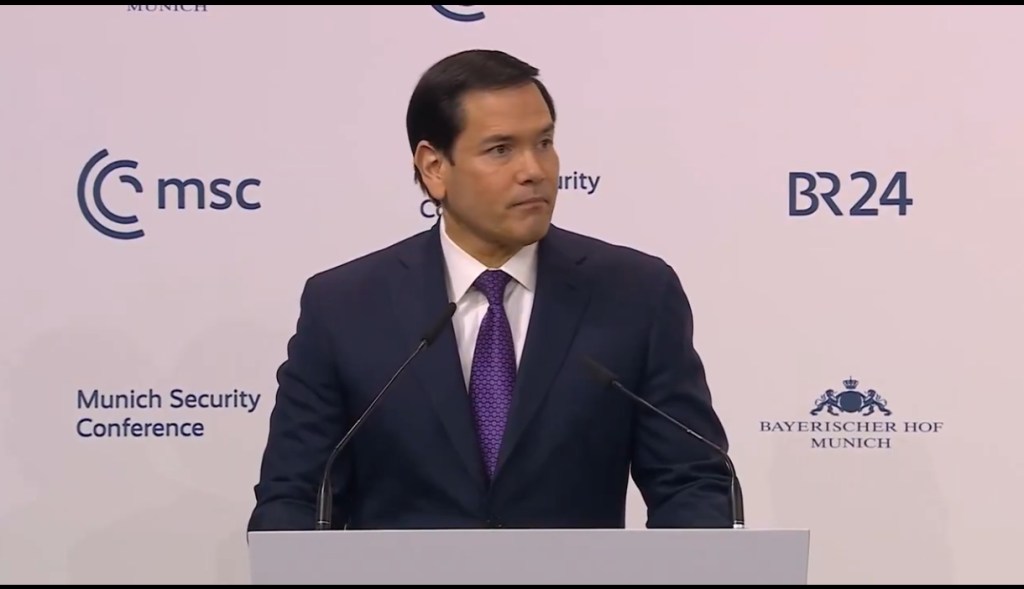

Marco Rubio’s Munich Declaration of Colonial Revivalism amid the Crisis of Western Primacy and the Rise of the Global South

Marco Rubio used the Munich Security Conference to present a civilisational argument grounded in imperial expansion and Western dominance. He declared that “for five centuries, before the end of the Second World War, the West had been expanding – its missionaries, its pilgrims, its soldiers, its explorers pouring out from its shores to cross oceans, settle new continents, build vast empires extending out across the globe.” That description treats conquest and settlement as civilisational achievement rather than coercive domination backed by naval power, chartered companies, and racial hierarchy.

Rubio then framed the post-1945 period as aberration and retreat. He lamented that “the great Western empires had entered into terminal decline, accelerated by godless communist revolutions and by anti-colonial uprisings that would transform the world and drape the red hammer and sickle across vast swaths of the map in the years to come.” Anti-colonial movements across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East were thus presented as foreign ideological contagion rather than indigenous demands for sovereignty. Historical scholarship demonstrates that decolonisation drew upon local political organisation, wartime mobilisation, and economic grievance long preceding Soviet alignment, as documented by Prashad (2007) and Darwin (2008).

Rubio argued that Western predecessors “recognized that decline was a choice, and it was a choice they refused to make.” He called upon allies to reject “the West’s managed decline,” to revive “the West’s age of dominance,” and to “renew the greatest civilization in human history.” Such language links contemporary security policy to restoration of hierarchical primacy rather than accommodation within an emerging multipolar order. John Mearsheimer has argued that liberal hegemony after the Cold War reflected an attempt to entrench unipolar dominance despite structural shifts in power distribution (Mearsheimer, 2018). Rubio’s speech aligns with that impulse toward primacy rather than adjustment.

Overt colonial rule after 1945 receded, yet patterns of extraction and control persisted through new mechanisms. Kwame Nkrumah described neocolonialism as indirect control exercised through finance, trade dependence, and political influence rather than formal annexation (Nkrumah, 1965). Postwar institutions, including the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, structured lending conditions that often constrained domestic industrial policy in indebted states. Jeffrey Sachs has criticised structural adjustment programmes for deepening poverty and limiting developmental sovereignty in parts of Africa and Latin America during the 1980s and 1990s (Sachs, 2005). Maritime dominance of sea lanes by the United States Navy secured global trade flows under American strategic oversight, embedding supply chains within a security architecture centred on Washington.

Regime change operations and covert interventions reinforced that architecture. Declassified records detail United States involvement in Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973, and numerous other theatres during the Cold War. Richard D. Wolff argues that such interventions protected corporate and financial interests tied to resource extraction and market access (Wolff, 2012). The stability doctrine often translated into managed instability, where perpetual crisis justified external presence and security assistance. Military bases across Africa and the Middle East anchored influence even as formal empire disappeared.

Rubio’s denunciation of anti-colonial uprisings as communist subversion obscures this transformation from overt colonialism to networked imperial management. Supply chains integrated raw material production in the Global South with manufacturing and finance in the North Atlantic. Debt dependency and currency hierarchies anchored by the dollar system entrenched asymmetries in capital flows. Mearsheimer has noted that great powers seek to maximise relative power within anarchic systems, yet he also recognises that structural change limits capacity to sustain primacy indefinitely (Mearsheimer, 2014). Current shifts in global output toward Asia reflect those limits.

China’s rise and the expansion of BRICS signal an awakening among states seeking policy space outside Western-dominated institutions. World Bank data indicate that China’s GDP measured at purchasing power parity surpassed that of the United States during the previous decade. Sachs has argued that sustainable development requires multipolar cooperation rather than bloc confrontation, emphasising that emerging economies now possess financial and technological capacity to pursue independent strategies (Sachs, 2020). Wolff interprets the relative decline of the West as consequence of internal inequality and deindustrialisation, compounded by external competition (Wolff, 2018).

Within that context Rubio portrayed migration, climate policy, and multilateral law as symptoms of weakness undermining Western identity. He characterised climate commitments as submission to a “climate cult,” and he implied that adversaries exploit international law while the United States uses force to restore order. Such framing reduces legal norms developed after 1945 to obstacles against renewed dominance. Hedley Bull’s conception of international society based on sovereign equality stands in tension with hierarchical revivalism.

European delegates reportedly offered a standing ovation when imperial expansion was praised and anti-colonial movements were denounced. Applause at that moment reverberates across societies whose histories include forced labour regimes, extractive taxation, and externally supported authoritarian governments. Fanon described colonial order as sustained by violence and racial compartmentalisation (Fanon, 1961). Contemporary memories of intervention in Iraq, Libya, and elsewhere reinforce suspicion that humanitarian language can mask strategic objectives.

Rubio emphasised that the United States would “always be a child of Europe,” aligning American identity with European settlers who displaced indigenous populations. That identification foregrounds colonial lineage over plural heritage within the Americas. Assertions of democratic mission must be considered alongside domestic revelations concerning elite networks and opaque influence. The exposure of associations between senior political figures and Jeffrey Epstein intensified public concern regarding concentrated power operating beyond electoral accountability. Gallup surveys over the past decade record declining confidence in Congress and major institutions, suggesting erosion of perceived democratic legitimacy.

Rubio’s speech therefore arrives at a moment when Western claims to moral leadership face scrutiny both abroad and at home. The Global South now pursues nationalisation of minerals, industrial policy, and social welfare expansion within sovereign frameworks. Burkina Faso’s reduction of prescription medication costs and moves toward resource nationalisation represent exercises of domestic authority rather than ideological insurrection. Characterising such measures as existential threats risks justifying renewed pressure through sanctions, financial leverage, or covert destabilisation.

Mearsheimer contends that great powers must recognise spheres of influence and limits imposed by rival capabilities to avoid catastrophic conflict (Mearsheimer, 2014). Sachs argues that cooperative multilateralism anchored in the United Nations Charter offers more stable path than attempts to perpetuate unipolar dominance (Sachs, 2020). Wolff frames current tensions as symptoms of systemic transition from one centre of accumulation to multiple centres (Wolff, 2018). Rubio’s call to revive “the West’s age of dominance” stands at odds with these assessments of structural change.

Decolonisation dismantled formal empire yet left legacies of economic asymmetry embedded within global institutions. The language once used to justify plunder under civilising missions encounters growing resistance from societies conscious of historical extraction. Digital communication and regional coordination amplify that awareness, reducing effectiveness of narratives equating Western security with universal good. Multipolarity reflects demographic weight, economic redistribution, and political assertion by states long subordinated within imperial hierarchies.

Security discourse that equates pride with dominance risks escalating confrontation in a world where nuclear deterrence constrains direct conflict among major powers. Sovereign equality under international law remains fragile yet foundational. Rubio’s Munich address signals dissatisfaction with post-hegemonic adjustment and hints at reassertion of hierarchical order. Such direction would carry profound implications for the Global South, whose development trajectories depend upon freedom from coercive intervention and externally imposed economic constraints

In essence, Rubio stood in Munich and praised those who “settle[d] new continents” and built “vast empires,” then condemned anti-colonial uprisings for having “drape[d] the red hammer and sickle across vast swaths of the map.” That framing treats decolonisation as mistake and dominance as virtue. When he calls for reviving “the West’s age of dominance,” governments in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia should hear a policy signal, not nostalgia. John Mearsheimer has written that great powers in relative decline often act aggressively to preserve primacy rather than adjust to new balances (Mearsheimer, 2014). Richard D. Wolff argues that economic decline at the core drives external pressure to secure resources, markets, and strategic routes (Wolff, 2018). Countries pursuing mineral nationalisation, industrial policy, or alternative financial partnerships should therefore expect harder use of sanctions, debt leverage, political interference, and maritime control justified as defence of order.

Formal empire ended, yet control continued through finance, supply chains, military basing, and regime alignment. Kwame Nkrumah defined this structure as neocolonialism, where a state appears independent but its economic system is directed from outside (Nkrumah, 1965). Jeffrey Sachs has warned that refusal to accept multipolar cooperation will fracture the global economy and damage development prospects across the Global South (Sachs, 2020). Rubio’s language signals resistance to multipolar adjustment and preference for restored hierarchy. The Global South should read this speech as advance notice that sovereign development will be tested, pressured, and, where possible, constrained. Nkrumah’s warning remains direct: “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent… In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside” (1965).

Authored By: Global Geopolitics

Thank you for visiting. This is a reader-supported publication. You can support by way of a cup of coffee:

https://buymeacoffee.com/ggtv or

https://ko-fi.com/globalgeopolitics

References

Darwin, J. (2008). After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire since 1405. London: Penguin.

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth. Paris: Maspero.

Gallup. (2023). Confidence in Institutions. Washington, DC: Gallup Analytics.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2014). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (Updated ed.). New York: Norton.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2018). The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. London: Thomas Nelson.

Patnaik, U., & Patnaik, P. (2017). A Theory of Imperialism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Prashad, V. (2007). The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: New Press.

Sachs, J. (2005). The End of Poverty. New York: Penguin.

Sachs, J. (2020). The Ages of Globalization. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wolff, R. D. (2012). Occupy the Economy. San Francisco: City Lights.

Wolff, R. D. (2018). Capitalism’s Crisis Deepens. Chicago: Haymarket.

Leave a comment